-853X543.jpg)

Different Strokes

by Khalid Mohamed February 18 2022, 12:00 am Estimated Reading Time: 9 mins, 50 secsManoj Bajpayee, in a heart-to-heart conversation with Khalid Mohamed, on his journey right from the mercurial gangster Bhiku Mhatre of Satya and the royal Victor of Zubeidaa to the restrained spy of the series The Family Man… and the shape of more implosive performances to come.

Twenty four years after his breakthrough, award-grabbing performance as the mercurial gangster, Bhikhu Mhatre, the 52-year-old actor is in an upbeat zone.

Straddling the worlds of both unconventional and mainstream cinema - lately more on streaming channels - he hasn’t lost an iota of a newcomer’s zeal to shine a light on roles, which vary from the intense to the feather-light.

In fact, whenever a new film or series of his is ready to go, Manoj Bajpayee exudes a sense of wonderment. “Hey is that me, a boy from a smalltown of Bihar, up there on the screen?”

This guilelessness also sets Bajpayee, winner of three National Awards for Satya, Pinjar and Bhonsle, apart from a majority of contemporary actors, who give assent to interviews, which are closely monitored by their PR agents.

Which is why when I met him, after years, at a studio for a Q&A, there were no off-the-record statements, no ducking of questions, no predilection for projecting a squeaky-clean image. Here, then, are excerpts from our conversation:

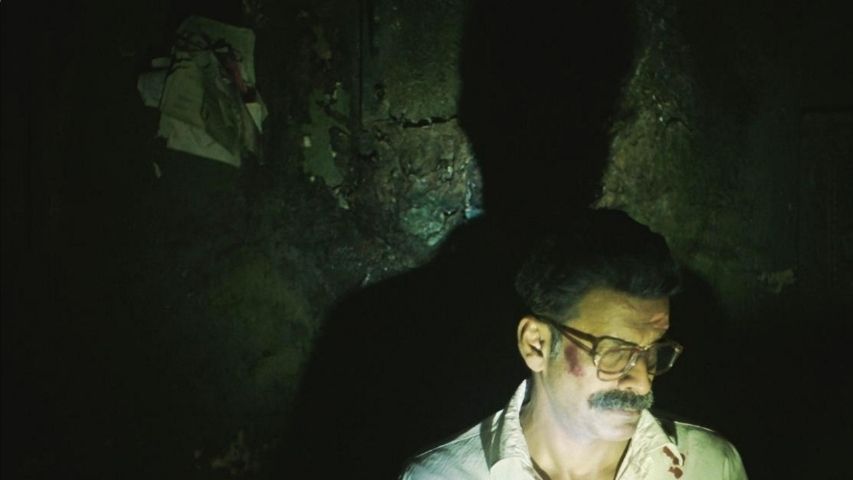

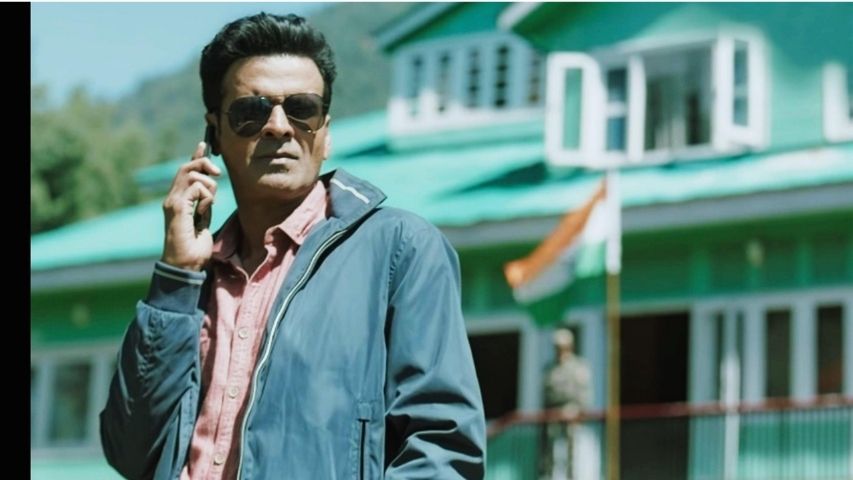

Your Amazon Prime Video series The Family Man (Seasons 1 and 2), as Srikant Tiwari, an intelligence officer - a spy, saw you in a decidedly different image as a middle-class man striving to balance his professional and personal lives. Did you foresee its tremendous impact?

I’d say when an actor is undergoing the process of creating any role, its impact can never be predicted. You can’t comprehend anything else but the fact that you’re in a work in progress.

Ever since there was a boom of OTT fare, I was flooded with offers. That propelled me to check out each and every OTT platform. I wasn’t getting any role, which went against the hackneyed template, of a gun-toting mafia don, a cop, a cog in the wheel of crime thrillers. I had resolved not to play mafiosis anymore - in a way they were all variations of Bhiku Mhatre of Satya in a different garb. I definitely knew what I wasn’t looking for.

Then the creators of The Family Man, Raj and D.K., asked for a meeting at Indigo, a restaurant close to my house. I thought I would decline politely but within 20 minutes of their narration, I could make out that my character, Srikant Tiwari, would connect with the viewers. Spies are always glamorised, they are larger-than-life. This guy was absolutely ordinary, with no swag, spending hours travelling in buses and local trains. He was the kind of man who despite his extraordinary work has never been celebrated through his life. I said ‘Yes’ even without reading the script. All I asked was for two or three episodes, which may have already been written. On reading them, I was in without a second thought.

When I started prepping, the concentration was upon making Srikant a common, every day kind of man you could pass by on the street. His job is demanding as his contribution to his home chores. Inevitably, there are long spells of absence from his family.

For the characterisation, I borrowed elements from the behaviour of my father, brother, some friends and of course, myself. I surmised that if I could somehow convey the feeling of being a fly on the wall, I would get the performance right.

How do you go through this preparation process?

By making mental notes but more than that, jotting down notes on chits of paper. I don’t maintain a diary or a file for such notes. I jot them down on chits of paper. A week or 10 days before the shoot, I memorise them and dispense with the notes.

Did you have to make changes in your performance during Season 2?

Before starting on Season 2, I watched the first one again. I think I had already got the nuances right, but now I had to be more conflicted and confused, both professionally and personally. The struggle to keep his home intact was slipping like sand through Srikant’s fingers. This complexity had to be enacted subtly at a low key, without the slightest degree of becoming overwrought or indulging in high dramatics.

When will Season 3 be on?

Some time next year. I’ve already committed to my dates.

Were you gratified by the armful of awards for the performance?

(Laughs) I’ve been so disappointed initially in my career, that I’m quite detached about awards. If I’m given an award, I accept it humbly.

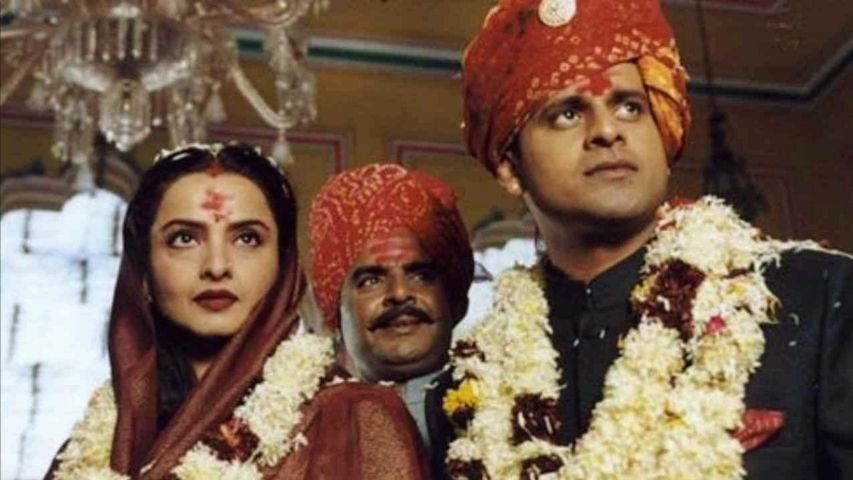

Why have you never been offered a role like that of Victor of Rajasthan royalty in Zubeidaa, ever again?

See, casting me as Victor was entirely Shyam Benegal’s vision. Only he could have imagined me in a role like that of Victor’s and have the guts to go ahead with it. The memory of learning from the maestro will always be with me. His brilliance is such that he can sit down with you and talk about any topic under the sun.

Weren’t you supposed to do your first kissing scene in Zubeidaa?

Trust you to bring that up. (Jokingly) I’m no Emraan Hashmi but you may be surprised by what you see in my future work. Of late I’ve completed Abhishek Chaubey’s untitled film, Despatch by Kanu Behl who made Titli, and director Raam Reddy’s film - he made Tithi. It’s tentatively titled In Pahaadon Mein. They’re all different kinds of roles, which are away from stereotyping me. We’re hoping that the pandemic conditions will improve to release them at theaters. Who can say anything categorically at this point?

And there’s a project with Anurag Kashyap, which we aim to produce together, one with Neeraj Pandey, one with Devashish Makhija who made Bhonsle, and with Rahul V Chittella, who used to be Mira Nair’s assistant. So, unfortunately I’m hardly ever at home like The Family Man. Fortunately my wife Shabana and 11-year daughter, Ava, keep me grounded, and I really hope and think they understand my work pressures.

Can you honestly claim that at any point of time you have topped your tour de force performance in Ram Gopal Varma’s Satya?

There has never been any intention to top any performance. I’ve always looked for strong roles and attempted to do justice to them. Some have been of the same calibre, some have been more evolved than that of Bhiku Mhatre. I think Pinjar (2003) was my career-best. I’m also extremely proud of Gangs of Wasseypur (2012) and Aligarh (2016). And there was Raajneeti (2010), which made me understand the craft of speech to accentuate the oratory skills of the politician I was enacting. I’m afraid very few actors work on their speech, their dialogue pitch and dialect, nowadays.

It’s tragic. Ever since the 1990s, no one speaks Hindi, no one has the knowledge of Hindustani (a blend of Hindi and Urdu). Even assistants on the sets speak in English. Scripts are no longer written in the Devanagari script. Whenever I ask for a script in Hindi, I get a strange reaction, as if a dog had bitten me.

Who reads scripts? The Bollywood custom is that actors have to be given a long-winded narration.

Believe it or not, the actor you’re looking at right now, reads scripts.

Aren’t you sorely disappointed when socially purposeful, small-budget films of yours like Rukh and Budhia: Born to Run don’t get their due audience?

See Rukh and Budhia were extra-intense, dramatic and were targeted at a niche audience. Today there are far many more avenues, the streaming channels, especially, to get back a film’s investment and decent profits. Contrary to popular belief, small films don’t lose money at all. There has to be a spirit of idealism among the actors and technicians.

When a film is made with the aim of telling a powerful story, we have to agree happily to take a cut in our salaries. However, if I’m cast in a big-budget, fun film like Baaghi 3, with Tiger Shroff in the lead, I expect to be paid in accordance with the project’s overall budget.

Doesn’t every actor come with a price tag? Corporates bankroll films in accordance to a star’s market equity.

True, but what can an artist do? We’re thick-skinned rhinos. Mercifully being the kind of person and actor I am, there’s no greed for money. As long as my family and I can live comfortably, the role matters more than the pay packet. The most expensive thing I’ve ever bought in my life is the apartment we live in. I don’t shop at malls for expensive gifts for my wife (actor Neha nee Shabana Raza). If I were to buy her a piece of jewellery or perfume, she’d think I’ve gone crazy. In any case, she doesn’t approve of my taste in such things.

You’ve acted in approximately 85 productions till now. How many of them were, let’s say, awful?

At least 20 of them were awful. I wouldn’t name the films because these were choices made out of needs and circumstances: to run the kitchen. I’ve been a responsible father to our daughter, but, as I said, not as hands-on as I could have been. I hope to rectify that.

You were quite gung-ho about Aiyyary (Shamsters) directed by Neeraj Pandey.

Absolutely. Neeraj is fastidious about his script and technique. Like me he isn’t the sort of guy who hangs around in social circles, to be seen at the right place at the right time. He tells important stories in a way that they reach out to a wide audience.

That sounds very much like the Ram Gopal Varma of yore.

Not at all. There’s a difference of 360 degrees between them. Ramu is unpredictable, you can never figure out what’s going on in his mind. Neeraj is very organised, precise and in harmony with his actors. There are no last-minute arguments on Neeraj’s sets. If any actor wants a clarification, that’s discussed and resolved at the scripting stage.

A phalanx has emerged of game-changing actors led by Nawazuddin Siddiqui, Rajkummar Rao and Pankaj Tripathi. Do you feel the competition heating up?

How can you say that? We belong to different age-groups. They can’t do my roles, neither can I do theirs. For instance, I can’t imagine myself in Newton or Trapped. While acting with Rajkummar Rao in Aligarh and Chittagong (2012), I could see he is a hardworking and committed actor. Nawazuddin has his own distinct persona.

I’m particularly proud of Pankaj Tripathi. Both of us are from Bihar, where family responsibilities are such that you can’t even dream about becoming an actor. Their parents hope that their children will grow up to become bank officers, district magistrates or police officers. Often I feel if I hadn’t left home, I would have become a farmer, content to be at home with his elders, his wife and a flock of children.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)