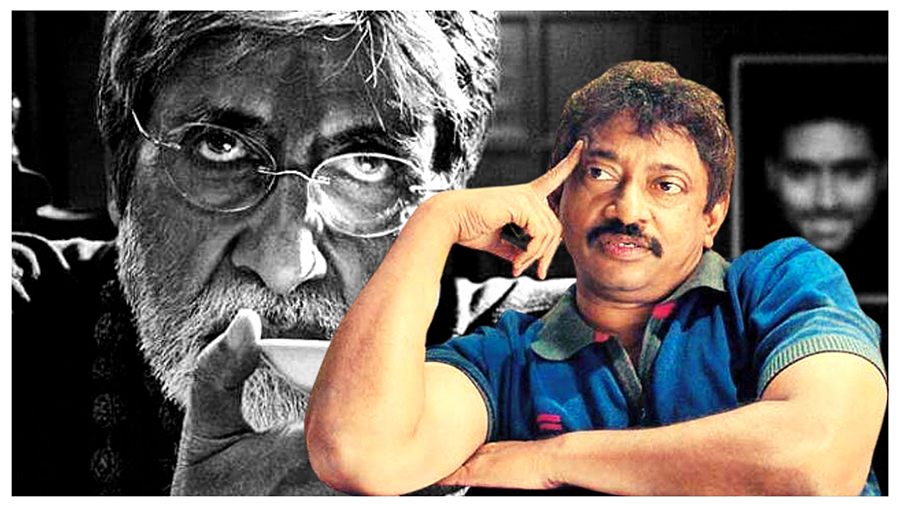

Khalid Mohamed’s never-before published interview with the dogged rule-breaker, Ram Gopal Varma on how to make a film, from its script and set designs right down to direction.

He can be infuriating, a put-downer of say Iranian and global cinema. Yet knowing Ram Gopal Varma, when the sun was shining brightly upon him during the late 1980s to the earlier stretch of the 2000s, I would crave to converse with him on cinema, which he would hack out by the dozen from his company, aptly called The Factory.

I was commissioned to do a book on him in an interview format; every chapter would be in a varied style. It was to be titled Rogue Thinker, which he approved. The publishers, however, withdrew, informing me that their marketing team had concluded he wasn’t saleable anymore, especially after his yet another probe in the Mumbai underworld, Department, headlining Amitabh Bachchan and Sanjay Dutt sank like the Titanic.

He can make plenty of sense in his approach to filmmaking, and he can be awfully self-righteous. I still nurse a sneaking respect for him though. Super successes or calamitous failures, his mantra is: this is the way I am on my twitter handle, as a filmmaker and dare I add human being. He can be whimsical, suddenly handing me an unused poster of Satya, saying, “You collect such trivia, no?”

Right now, he appears to have exited Mumbai for his birth-town Hyderabad, has announced that he is introducing an OTT channel Spark, by streaming his film D Company, and is cruelly dismissed as ‘burnt-out’. It’s only a few directors like Dibakar Bannerjee who acknowledge that he was the trendsetter for the seamier slice-of-life films on his own independent terms.

Be that as it may, here, then, are his so-far unpublished views on the key departments of constructing a film, quintessentially RGV-style:

The Write Way: How a script germinates

Right from my first film Shiva onwards, I think in terms of shots rather than a script. There is an idea of a plot - like say, a man’s journey into gangster-dom. Immediately, visuals arise rather than pages of prose. If I were to work with an inflexible script, the film would go haywire halfway. That has happened whenever I’ve made the mistake of following a script. Anything worthwhile that I’ve made has been accidental.

I started writing a script only with Company. By contrast, Satya didn’t even have a one-line outline of the progression of scenes. Credit cannot go to any one or two scriptwriters for Satya. If I adopted the traditional mode of a script for Company, it was to make the film’s daily production smoother. My assistants had to know where and what we were going to shoot next, in Mumbai and abroad. Yet the Company script wasn’t inscribed on stone, I kept changing it every day.

In a script, the practice is to specify whether a certain character will be standing or sitting; the entire body lingo is premeditated. That doesn’t work, a character’s body language has to be altered depending on the location we have found, the dialogue that has just been improvised and the lighting chosen for every scene.

The importance of paperwork in filmmaking is exaggerated. A film unspools in the creator’s mind, not on sheets of paper. Robert Towne’s script for Roman Polanski’s Chinatown is said to be perfect, but it bored me.

I second Oliver Stone’s statement that “a script is basically a collection of moments.” Like him, I am not respectful about scripts. It may suit other filmmakers, it doesn’t suit me at all to know every moment and nuance, which I will shoot next.

Dialogue writing is believed to be a part of scripting. Again that doesn’t work for me. Perhaps because I insist on minimalist, functional dialogue, what people would say in real life rather than in film life? Brief, colloquial, of-the-moment dialogue suits my subjects rather than flowery or fiery monologues and speeches. Mushy dialogue gives me an allergy.

Best written films according to RGV: Carl Foreman’s Mackenna’s Gold, William Friedkin’s French Connection and The Exorcist.

Sound: Ear friendly

I am very particular about sound. In our movies, songs are not shot in real time. Camera angles and cuts bring coherence to the songs. The sound has to be kept uniform although there are jumps in time as well as space. From a nightclub, a dance may suddenly shift to a city’s street. The sound has to alter slightly but cannot be jarring.

Background music and sound effects are a key part. The atmosphere has to be absolutely realistic. Mainstream movies go over-the-top throughout a film’s duration. The heightening and lowering of volume is an art by itself, it has to be achieved at the precise split second moment.

In Shiva, I kept the atmosphere sound subdued but simmering. In Bhoot, particularly, it was essential to blast the sound after an oppressive stretch of silence. That was to scare the viewer, make the audience feel that a ghost could pounce right there and then on them in the cinema hall.

Best sound design according to RGV: William Friedkin’s The Exorcist

Editing: Cutting edge

Editing is a perspective, a way of seeing. It’s the way a director wants the audience to see his film. Editing, above all, decides the extent of how long a shot must ‘hold’ or retreat to create its desired effect. For instance, if you want the audience to feel a character’s emotions at a point of time it must cut away before the viewer is likely to get fed up of the shot.

A fast tempo doesn’t necessarily mean jump cuts and MTV-style flash shots. A tempo isn’t determined by the genre of a film but by the director’s attitude. I avoid clutter and any repetition of information already given to the audience.

Many of our films suffer from spending too much time in establishing the characters the way TV serials do. The main story is important, not the backstory. For instance, if a guy has come to Mumbai to improve his life as in Satya, I don’t necessarily have to go into the details of the place he came from and all the misery he suffered. That is implied by the very fact that he has left home for what he believes to be the City of Gold.

Editing can enhance or diminish the impact of a moment. Like I remember Raghavendra Rao’s Himmatwalla. There was a long-distance shot of Sridevi showing her famous ‘thunder thighs’. That was exciting but the immediate next shot was a close-up of Sridevi’s face, which ruined the impact of her sensuality.

A transition from one scene to another is often conveyed through shots of skyscrapers, sunsets and sunrises. That is hopelessly conventional unless the skyscraper plays a ‘character’, like it did in the case of the haunted apartment in Bhoot.

Sharp editing can be especially effective in transitions without being obvious. The way Steven Soderbergh’s Erin Brokovich cut from Julia Roberts speaking to someone across a desk, to a person at another desk, was fantastic. That was so economical; no footage was wasted showing her move from one office to another.

I don’t sit on the editing after a film has been shot. The editor makes a first cut and then I alter it, often drastically, rearranging the shots, throwing away many of the ones, which don’t work.

A director shouldn’t be so excessively in love with his work that he cannot see a single frame cut. Perhaps that’s why you find so many of our films with redundant scenes. The director doesn’t have the heart to bin them just because he shot them, never mind the final effect.

Best-edited films according to RGV: Oliver Stone’s Natual Born Killers and Rodrigo Cortes’ Buried.

Cinematography: Visual instincts

I have no hesitation in saying this. If top cameramen feel offended about this, so be it. Truly, I believe that cinematography is overrated as an independent art form. Anyone who operates a camera for six to seven months can photograph a film. Ultimately, it is the director who decides on the visuals, lighting and the general look. Since I shoot on real-life locations and always try to use natural lighting, the Director of Photography (DOP) merely serves as the executor. Over the years, I have operated the camera myself though not as a rule.

The task is to get the actors to perform and capture them from the point of view, which is relevant to the moment. A director instinctively knows the angle he wants, not the cameraman. When crowd scenes, like say in a sports stadium, have to be filmed, multiple camera set-ups are essential. Again, the director knows exactly, which angles he wants so that the editor can put them together later.

I don’t go in for too many angles though; the editor doesn’t have too much material to play around with - perhaps because I’m clear about what I want. Like a reporter should know exactly how many words he needs for his article. Overshooting only creates confusion besides being a waste of resources.

I admit that I have tended to overuse the hand-held camera, Steadicam and the Jimmy Jib. Today, straight, unfussy shots work - lensed from an angle, which makes the audience feel that he is right there on the screen, almost as if he is participating in the events.

Best film for photography, according to RGV: Robert Wilson’s B-Grade Slasher Dead Mary

Art direction: sets appeal

Mani Ratnam takes a considerable amount of interest in set design and décor. I don’t. The patterns on the curtains, the paintings on the wall, the knick-knacks don’t matter to me as long as they aren’t jarring.

The interiors have to look as realistic as possible, and so it’s best to shoot in real locations instead of creating them. I have used studio sets very rarely, like say for one-fourth of the song Mangta hai kya in Rangeela, and for Mast, which was supposed to be about a show business fantasy world. For dream sequences, sets may be essential, but not for my kind of cinema which attempts to come as close to real life as possible, good, bad or plain ugly.

Best-set-designs according to RGV: Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Saawariya, ha ha!

Action: Politics of punching

Raw action has to be orchestrated, almost choreographed. The violence has to be integrated with the emotional states of the characters. Otherwise the action will be like a cartoon strip, full of sound and punches, signifying nothing. In fact, it is the static moment between a fight, which makes an impact, which is what I sought to achieve in the opening action scene in Shiva.

The director and action director have to be in synergy. And I have worked with action directors who understand that, like Raju Master (Shiva), Horse Babu (Kshanam Kshanam), and Alan Amin (Satya, Company).

Unfortunately, the concept of action is quite strange in our films. It is left to the action director to conceive and execute the entire scene. Our directors often take a holiday when the ‘specialists’ are doing the action for them. Perhaps that’s why even the best of our action movies in Mumbai are very sub-standard.

Currently, Tamil and Telugu cinema are far superior to Bollywood when it comes to action. The stunts and fights in the film Magadhira were amazing. In Mumbai, comedies and romances are the flavor of the season. Hero-centric, macho films are being made only once in a while, and they are nothing to rave about.

Best Action Film according to RGV: Die Hard 4.

Choreography: Dance, baby, dance

The joy of dance comes through the characterizations. Instead of just breaking into dance, without warning, a character should have a reason for doing that, and express her or his mood of the situation.

Even if there’s an item song, it has to be relevant. It has to come as a relief from the intense events, establish a mood or even divert the viewer’s attention from the plot for a while.

Quite often, the results can be fantastic, by accident. Saroj Khan was to do the choreography of Yaaron Sun Lo Zara (Rangeela). The unit had gathered at Madh Island but Saroj Khan, at the last minute sent word through her son Ahmed Khan, that she could not make it because of some other commitment. I was extremely upset, and asked Ahmed that if he wanted to start off as an independent choreographer, he could choreograph the number right there and then. And he did.

I enjoy filming songs and dances if I like the girl who’s dancing, which I do most of the time.

Best-choreographed film according to RGV: Singin’ in the Rain.

Costume design: cool and casual

I’m not fussy about costumes, as long as the designer can achieve the look that I want. Like the look of Amitabh Bachchan in Sarkar was finalized in five minutes. He was given a black lungi kurta and that was it. That, in fact, saved us money.

I want my heroines to look sexy, and they trust me. They know I will not zoom the camera towards their vital assets. Zooming in is bad manners.

Aamir Khan designed his own tapori outfit. Urmila Matondkar’s costumes for Rangeela became a trend although there was no extraordinary haute couture designing done for her. Basically, she carried off every stitch of clothing she wore with style. The white T-shirt she wore while running on the beach was borrowed impromptu from Jackie Shroff on location. And the red dress, worn for the song Hai Rama, was inspired by a costume from Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula.

Initially, Anna Singh who was the No. 1 designer then, was to do the costumes. But she was so busy that she ended up doing only Jackie’s. Neeta Lulla recommended Manish Malhotra, so he came in to handle Urmila’s wardrobe. Costumes are finalized in consultation with the artistes. They are finalized, taking their comfort levels and the look I have in mind. And I try to keep a real life reference in mind. So if I’m showing a character that’s a film director, he would dress up like Vinod Chopra or Shekhar Kapur do normally. A director on screen wouldn’t dress up like me, because I look like a ruffian.

Best film costumes according to RGV: None, except maybe Basic Instinct 2 in which Sharon Stone outfit at the police interrogation became a cult.

Direction: Integrating components

Unarguably, direction is not a primary art form. I can’t compose music or act but I can ‘direct’ the various disciplines towards a specific objective. To say that a director is the captain of the ship is not only outdated but also a mixed metaphor. Which ship is a film director navigating? He is not a captain, colonel or dictator, he is simply working towards creating a film, with various components, which will be seen - hopefully - by millions of viewers.

So, I would even say that there are no great directors in the world. There are only greatly directed films.

The Godfather, if it were to be remade by Darren Aronofsky (Requiem for a Dream, Black Swan), would surely be another greatly directed film. Or take Buried, in which nothing happens except an American soldier trying desperately to get out of a coffin somewhere in Iraq. Every shot, every cut, every piece of background music made me think constantly, “What a superbly directed film.” I am not sure whether the next film by its director Rodrigo Cortes, would be as effective, unless he once again hits upon a mind-blowing concept.

A natural-born director will want to keep on making films, get up in the morning every day and go for the jugular. He should know and understand his audience. That’s why I can’t quite understand why some of our directors long to go international, Hollywood and all that. The names of big studios and its bigger bosses don’t interest me. I can never aspire for Hollywood because I know thousands of directors there must be superior to me.

Neither can I aspire to make quick bucks by directing ad films. How can I make an ad for a brand of tea when I can’t boil myself a cup of tea? If the ad was for a woman’s sensuality, maybe, that would interest me.

Right at this moment, after decades of filmmaking, I feel I’m a cinema terrorist. I’m bursting with energy, there are 1000 movies going on my head. The aim is to make as many of them, get on the road, have fun and get away with it. My flops don’t discourage me. There has never been a question of who will let me make another film again. The question is: who will stop me? No one can. I knew that from the moment I said okay to the first shot for Shiva.

Best-directed films according to: Steven Spielberg’s Jaws, Ole Bornedal’s Just Another Love Story

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)