Khalid Mohamed harks back to an interview with Jaya Bachchan on the art and craft of acting during her heyday under the helmsmanship of pre-eminent directors.

She’s an articulate, forthright Rajya Sabha member from the Samajwadi Party today, in her fourth term since 2004. The image in the public eye is that at the age of 73, she is Gibraltar - firm in her opinions, doesn’t exactly woo the press and is seen on Instagram, essentially in family photographs.

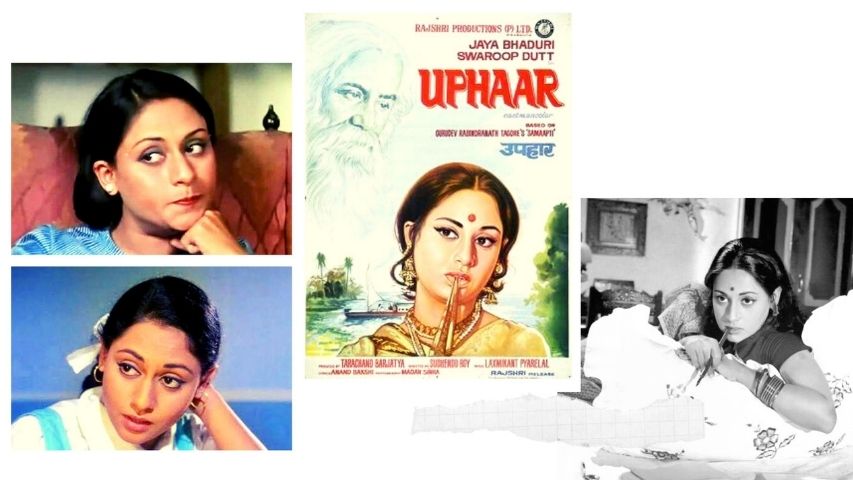

I bring up Jaya Bhaduri Bachchan, for this week’s column, to afford a glimpse of the consummate artist she has always been. At present, she is in the midst of participating in only one film, Rocky aur Rani ki Prem Kahani, directed by Karan Johar, whom she has known ever since he was in knee-pants. Naturally, her loyal fan base would like to see her much more often on screen.

I had lucked out when she had agreed to portray Nishatbi, a mother whose heart shattered to pieces on the disappearance of her son during the communal riots in Mumbai of 1992-’93, in Fiza (2000). I could detect an actor of fortitude, who often tapped her emotional memory of those dark and destructive days. She had opted for no make-up, playing the part to the core of reality.

No vanity, no embellishments, no demands for flattering costumes. Evidently because she firmly identified with the plight of so many Nishatbi’s whose sons had gone missing in the course of the riots. In fact, we had met one such mother in her Mohammed Ali Road tenement, before the shoot began. She hid her tears at the mother’s sheer haplessness. And I may add, her token fee for the project was close to zilch.

Before that, circa 1996, I had conducted an interview with Jaya Bachchan on her art and craft of acting. This was on a monsoon afternoon in her Juhu bungalow, over Hercules-strong mugs of coffee:

You were on a near-17-year hiatus from regular acting. Can an artist ever forget acting? Can one feel at sea facing the camera after a long break?

I don’t know about others but I can’t forget acting.

I don’t feel stonewalled or inadequate at all. It’s like starting all over again from where I left off. I’ve shot for Tapan (Sinha) kaku’s film, which forms a part of an anthology on Daughters of This Century, based on five short stories of Rabindranath Tagore. I haven’t made a big issue about this. I can do without the hoopla and remarks like, “Oh, she’s making a comeback, is she?”

One never leaves acting, there’s always the urge to do it again, the urge to continue with a vocation, which is as much a part of one’s life as breathing. Acting becomes as essential as having a square meal and drinking water every day of one’s life. Once an actor, always an actor. In Tapan kaku’s film, I play an ‘untouchable’ girl who decides to go and live in heaven. When she dies, her husband doesn’t have the few rupees to perform her last rites.

Weren’t you scheduled to start Baa Retire Thai Chhe directed by

the late Shafi Inamdar before the Tapan Sinha film?

Yes, we were about to start in a few months. It’s very important for me to strike a rapport with the director and the entire production team. Shafi had finalised the locations, he was raring to go when he passed away, which came as a shocking blow. (Note: subsequently she did act in its original version on stage, directed by Ramesh Talwar).

You didn’t have any hesitations about playing a grandmother?

None at all. Come to think of it, I’d love to be a grandmother on screen.

The ageing process has never bothered you?

Never! What bothers me is that business about dressing up snazzily and looking the way I did 10-15 years ago. Really, it’s such a pity that all film actors aren’t eligible for lead roles once they’ve crossed the age of 30 or 35 at most. There are no subjects, at present, for older artistes. Never mind, I’m not fussy about playing the main lead, as long as my character has some substance and depth.

Over time, you must have refused scores of offers.

I wish that was true but nothing worthwhile was offered to me. Neither Hrishi kaku (Hrishikesh Mukherjee) nor bhai (Gulzar) asked me to do anything for them. They probably felt that I wouldn’t agree or that I didn’t want to return. But believe me, I had never closed my doors.

What’s the greatest high for an actor – the fame or the fortune?

What’re you saying? Such things are not important for me at all. The greatest high is going through a gamut of characters, of leading so many different lives. To tell you the truth. I don’t see acting in a very involved manner. I remain a little detached while performing. After all, I’m not playing myself. Instead, I’m investing my imagination, impressions and observations into the character assigned to me.

An actor cannot imitate. So, I didn’t play Lata Mangeshkar while doing Abhimaan. Yet I did use bits of her and others to create a new entity. An actor has to use the face, body and voice she possesses. She cannot change herself physically beyond a point. She doesn’t want to do an impersonation or even a repeat performance of what she had done earlier.

There’s a catch though. After making a mark in one particular role, filmmakers keep coming back for more of the same. (Laughs) After Abhimaan and Anil Ganguly’s Kora Kagaz, they wanted me to play the ghar ki biwi over and over again. But I’m not the quiet, suffering wife, you know. I don’t bury my head into the sand like an ostrich. I shake off whatever is bugging me and move on. I don’t brood or sulk around in a state of depression.

Are you saying that you’re a happy person?

Hmm..well…basically I’m happy.

I would say that you’re rather serious.

Ha! Can’t serious people be happy? I can’t feel sorry for myself for too long. I may feel low for a while but then I pick myself up from the dumps and get going. It’s impossible for me to go around with a long face at home. Whenever that happens, my two children say, “Ma! Enough of that. Now chill out!”

What were you like as a child?

Very independent though not rebellious. We lived in Bhopal, in the kind of a house that my father, a journalist, could afford. It was a little house with a little garden. Even as a kid, my day would be full. I’d never get bored.

What did you look like?

What! How can I remember?

Try.

I’m told that my face hasn’t changed. Except, of course, now I’m sort of puffy and wrinkled. As a kid, I was quite bubbly. I was the eldest of three sisters, and quite bossy. I think I still am.

Our father instilled vital values in Neeta, Rita and me. He would stress the importance of being good, positive human beings. He never gave us sermons or lectures. He would correct us mildly and leave it at that. There would be lots of books, newspapers and press notes at home since he was a political journalist. I would read everything I could lay my hands on, be it in Hindi, Bengali or English.

Where did cinema figure in this world?

My father was progressive, we were sent to dance and music classes. The first film I saw was V. Shantaram’s Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje. I must have been 10 or 11 then. I saw it because my dance teacher had told me to, our parents were open-minded.

After Jhanak Jhanak… there was a long gap. From Nagpur we had shifted to Bhopal. I have faint memories of devouring samosas and watching the films of Dilip Kumar with my parents at night shows. Every Sunday, we would see a Bengali film; they were much better than what you see from Calcutta nowadays. I really loved Ritwik Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara, Mrinal Sen’s Baishe Srabon and Satyajit Ray’s Teen Kanya and Apur Sansar.

How well do you remember your first role in Satyajit Ray’s Mahanagar?

I remember going to Calcutta with dad, he had to meet some publishers in connection with a book he was writing. This was around the time of the Indo-China war in the early ‘60s. Tapan Sinha was shooting a film in Puri, dad knew him well and we went over to meet him.

We also met Sharmila Tagore, Robi Ghosh and Anil Chatterjee. Back in Calcutta, Sharmila and Robi kaku had recommended me to Ray. I used to wear specs, Ray told me to keep them on, only he gave me a thicker frame so that I looked nearly blind.

I did the role just as a lark. Ray was easy and gentle with me… he would just say, “Okay that’s fine… now just a look a little to the left… or right.” (Smiles) And he was always complimentary.

Did Mahanagar motivate you to take up acting?

I wasn’t bitten by the acting bug or anything as dramatic as that. But yes, I was motivated to see more films. I’d see anything. Dad would get upset and ask, “Why are you wasting your time on rubbish?”

He felt that I should go to the Pune Film Institute. The government was spending so much money on the place, he thought it would help me. So after clearing my higher secondary school, I was coaxed by my sisters to send in my application to the Institute. “Everyone goes to college, you’ll be doing something different,” they insisted. I was called for an audition, screen-tested and selected.

At the Institute, I felt a change within me. I started thinking seriously about acting, about cinema. I won a scholarship and stayed on to get my diploma.

Which films, Indian and global, would you recommend for the young generation interested in quality cinema?

We were extremely fortunate to be exposed to world cinema at the Film Institute, thanks to the National Film Archives in Pune. My suggestions would be quite a big bunch. These are the ones I can recall off-hand, D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation and Intolerance, Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane, Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, V.I. Pudovkin’s Mother and Storm Over Asia, the Akira Kurosawa collection from Rashomon to Madadayo, Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront and East of Eden. And Satyajit Ray’s Apu trilogy, Jalsaghar and Devi for the sheer economy and brilliance of the performances, Ritwik Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara, Sushil Majumdar’s Ballika Bodhu, Charlie Chaplin’s Gold Rush, City Lights, The Great Dictator and Limelight, Peter Seller’s The Party, Pink Panther and Being There… he could be so funny without being obvious, Ingmar Bergman’s Virgin Spring. Andrei Tarkovsky’s Sacrifice, V. Shantaram’s Do Aankhen Baarah Haath, Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zameen, Bandini and Sujata, Nitin Bose’s Ganga Jamuna… seeing Dilip Kumar’s performances in this one and Taraana is heartbreaking, Raj Kapoor’s Jagte Raho, Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa and Kaagaz ke Phool, Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Musafir and Anuradha, Shyam Benegal’s Ankur and Nishant, Giuseppe Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso and Michael Radford’s Il Postino.

How come you never acted for Satyajit Ray again?

Aah, that nearly happened. When I was at the Institute, I was offered a role in Pratidwandi. I was right in the middle of the course at the Institute, so it didn’t work out. I grumbled with him for a while. I was also offered Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome and Basu Chatterjee’s Sara Aakash. I couldn’t do them because it was felt if I left the Institute then my concentration would get distracted.

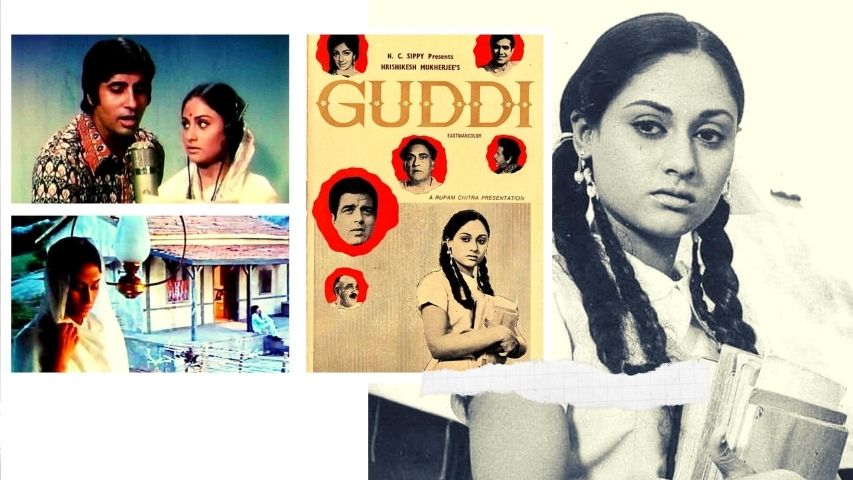

But you did do Guddi while you were still at the Film Institute.

Guddi happened while I was giving my final exams there. I completed the exams and immediately went to shoot for Hrishi kaku.

Can acting really be taught? Doesn’t it have to be ingrained in every performer?

I don’t think acting is an either/or thing. An actor must have the aptitude. If you work hard with the kind of technical support you have in cinema today, it’s not really difficult to become an actor. It’s so much easier today, you no longer need a face.

Wasn’t a face needed in the 1970s?

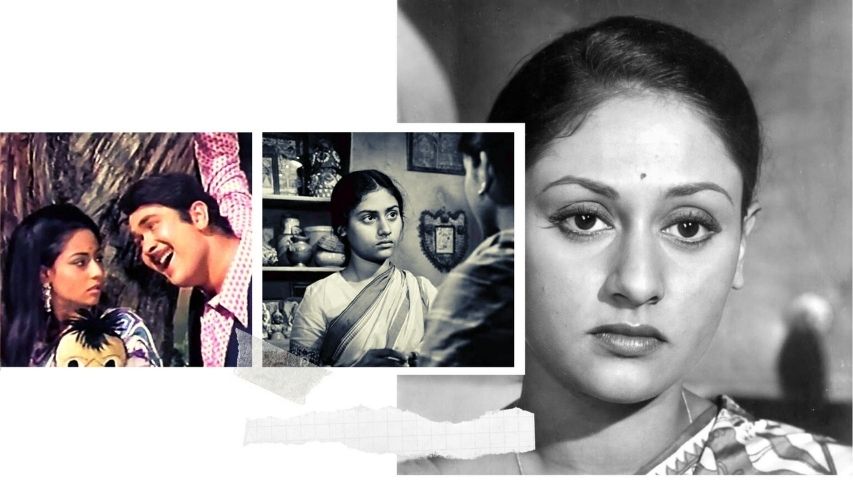

Ha! You’re looking at my face while asking this. Shweta was telling me the other day, “Mum, you weren’t a pretty face, you were different.” I came at a time when Sharmila Tagore, Mumtaz, Hema Malini, Asha Parekh, Sadhana and Saira Banu were going great guns. Around this time, the middle class was becoming more aware of cinema and cinema was coming of age in the Hindi heartland. Simultaneously, the parallel cinema was gaining momentum.

Perhaps, the middle class could identify with me. I wasn’t the usual schoolgirl in a tight salwar kameez, topped by a huge bouffant and carrying a badminton racquet. I came on the scene, wearing a plain school uniform. There was a childishness about Guddi, there was no forced sexuality, pouting of lips and those wet, rain-drenched scenes.

Could any one of today’s heroines fit into the role of Guddi if it were to be remade?

I don’t know if they would agree to shoot without make-up and frills. Kajol could. She is spontaneous and so unselfconscious about her appearance.

There was a time when Nutan, Tanuja, Waheeda Rehman and Farida Jalal were so wonderful. They were actors, not glamour dolls. In fact, I felt Waheedaji was a misfit in Shatranj in which they dressed her up to the hilt. I was aghast. How could anyone do this to her?

How come there’s been no second Jaya Bhaduri?

That sounds flattering. What can I say? Moushumi Chatterjee was a strong contender at one point. Pooja Bhatt is competent, she just needs the right platform. If she forgets about make-up and fancy costumes, she’d make a terrific impact. I am sure there are better Jaya Bhaduris around today who have a blast doing lighter roles.

Kajol has tremendous potential but I don’t know if she can ever come to the level of her mother. Tanu is amazing, so carefree, she doesn’t believe in props or supports. She does her own thing.

Know something? I’ve always found it difficult to look and act sad. I suppose when you’re interpreting a character, a little bit of your personality enters into it. Sorrow is certainly not my forte. Perhaps that’s why I relate best to lively people and lively characters.

You mentioned ‘props’ vis-à-vis Tanuja. Did you ever have to use them?

By props, I mean the perks associated with stardom - the image building, the PROs, the secretaries, the magazine articles saying how everyone from your parents to domestic helps are good and great. Tanu… or I, for that matter… never bothered about this contrived “good girl” image.

There was no need to create an aura or drama around us, which is perhaps why we came across as real. We didn’t hanker after the status of a star. What mattered was the role and doing it better than anyone else in the business.

Were you satisfied with the fees you were paid?

I was satisfied with whatever was given to me. The role came first, the money was secondary.

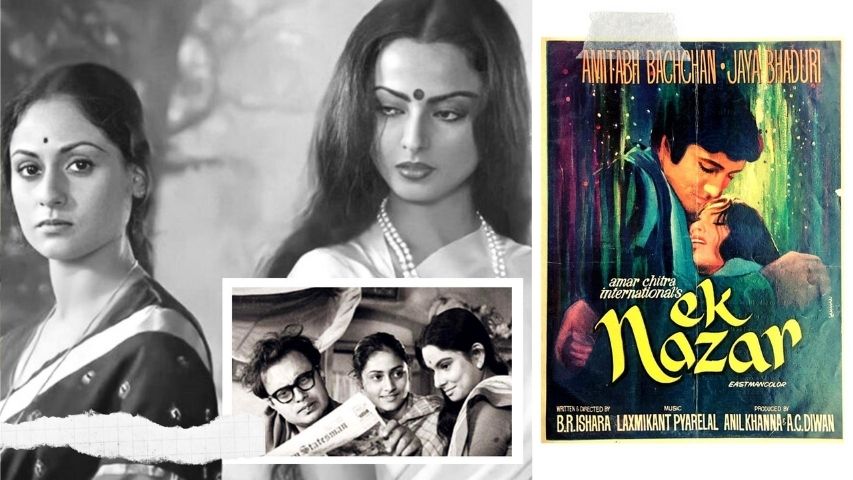

Are you embarrassed by any of your performances?

By that dance in Ek Nazar certainly, and by Bansi Birju in which I was terrible. In Samadhi, I just had to sit in a car and sing. Dharmendra was so sweet to me. When I was asked to do some weird steps, he said, “No way, you can’t make her do such silly stuff.” He made Samadhi so easy for me. Or else, I would have kept asking myself, “What am I doing out here? There’s no role for me.”

Do you notice the lack of films revolving around the young woman today - on the lines of Guddi and Uphaar?

The time for such films is returning. I feel sure that a revival is imminent in all art forms, be it in theatre, painting or cinema. The parallel cinema is becoming active again, filmmakers are recovering their confidence. They will not compromise with their creativity, at the same time they don’t want to make a film for a 10-seater preview theatre either. It’s important to connect with the audience. I’m sure they will create interesting characters and it doesn’t matter whether a man, a woman or a girl is at the pivot of the story.

Were you surprised by your ability to act?

I never ‘acted’ acted. I tried to be natural, nothing was done purposely or with pre-meditation. I hate breaking into melodrama and loud, throat-tearing scenes. I’m uneasy about doing songs and dances till today. What a torture it was doing that dance in Ek Nazar. In retrospect, I wish a duplicate had performed it for me, because I still look back fondly at the rest of the film.

You even won a dance competition in Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Bawarchi though!

Wasn’t that funny? The girl who was competing was a much superior dancer. Yet, I won. But then that’s the movies, the impossible becomes possible.

Mercifully, there’s been a gradual change. We have the anti-hero and we have the woman of mind instead of a woman of body. The heroine doesn’t have to be a goddess anymore, she doesn’t have to be perfect. It has been accepted that all of us are born with some flaws and frailties. That’s why maybe the vamps have vanished, today the heroines have grey shades and aren’t ashamed of them.

Speaking of grey areas, how would you rate Doosri Sita in which you played a murderer and convict?

Although the film (directed by Gogi Anand) became a bit morbid, it was an experience. Nearly 99 percent of the technical crew was from the Film Institute. I had to wear this dark makeup, which didn’t look authentic. I wish I had the patience to spend more time on it.

Doosri Sita had lovely music by R.D. Burman but the subject was far too revolutionary – a woman hacks her husband and mother-in-law to death. But today it seems so commonplace because you read about such incidents almost every day in the newspapers.

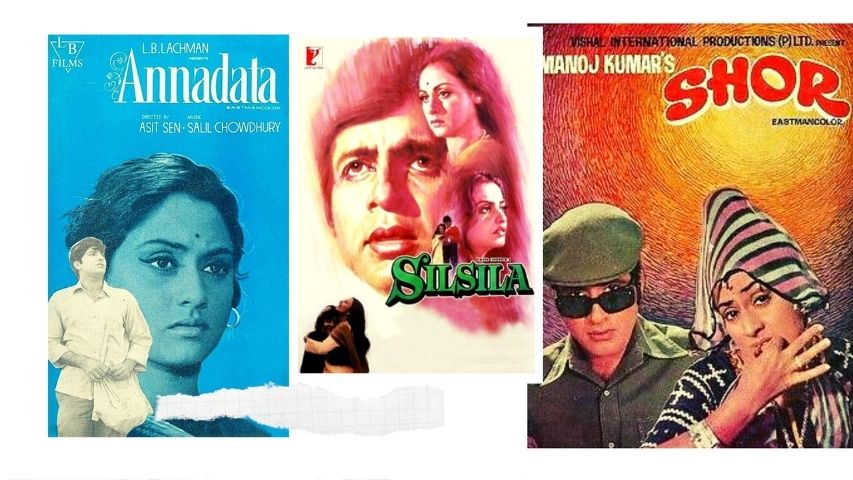

Asit Sen’s Annadata was a sensitive film, Were you disappointed by its commercial failure?

Annadata may not have created box office history but it didn’t fare too badly. Asit Sen’s shot takings were marvellous. Unlike the usual practice, none of the characters was shown standing still and delivering our dialogue. All of us were allowed to move as we would in real life and converse normally. For once, we could improvise and behave like real people and not like stage actors. While working with Basu Chatterjee on Piya ka Ghar, he would also be pretty relaxed with actors, and avoid artifice. Those experiences gave me a tremendous amount of self-confidence.

How much importance would you give to confidence? Isn’t there the danger of becoming all-knowing and cocky?

Maybe I used the wrong word. I meant confidence as being comfortable before the camera. If I ever felt awkward I would put my foot down. Like I had this massive argument with B.R Ishara over the rape scene in Ek Nazar. We sorted it out though. There was no tearing of clothes and stuff.

I had inhibitions whenever any kind of exposure was required. Mercifully, I was never asked to do any intimate or kissing scenes because I had come into the industry with the tag of a Hrishikesh Mukherjee heroine.

Would you have liked to portray a no-holds-barred vamp?

I would have loved to be a vamp but not the sort who wears long ostrich feathers, painted pointy nails and false eyelashes. It would have been a challenge to break the stereotype.

I suppose no filmmaker could imagine me as a she-devil. I was thought of as the girl from Guddi, Chupke Chupke, Mili, Koshish, Sholay and Kora Kagaz - not someone associated with NFDC cinema but as someone from the mainstream.

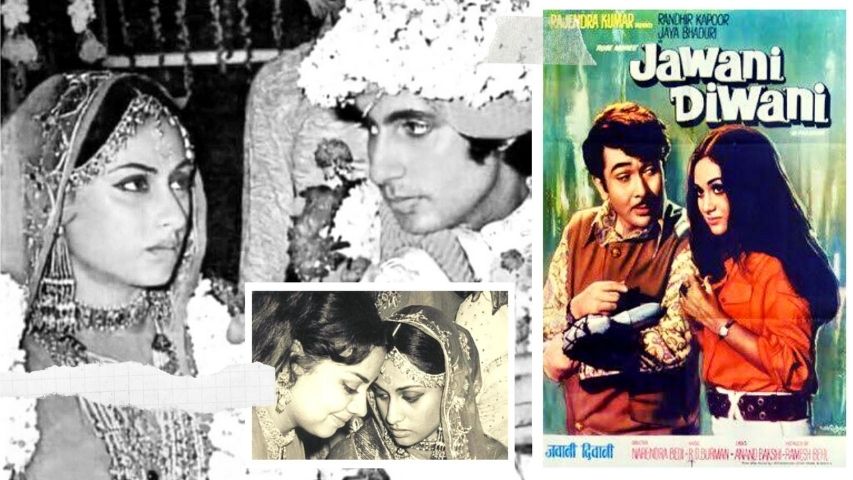

What about the stray glamorous roles as in Jawani Deewani?

(Eyes lighting up) I enjoyed Jawani Deewani thoroughly. It was young spirited. I never regretted doing it though wearing all those wigs and pancake was a big burden. The follow-up, Dil Deewane, didn’t work because because none of us worked with the same sincerity except its producer (Ramesh Behl).

On the other hand, there was plenty of sincerity from every artist in Rajinder Singh Bedi’s Phagun. That’s a film I’d like do all over again, only this time in the role of the mother, which was played by Waheeda Rehman.

Let’s come to your films with Amitabh Bachchan. Was there a special chemistry from the word go?

There was a special rapport between us, yes. We’d improvise very well with each other. He did the first shot of Guddi, then he was out. He was an unknown face when Guddi had started but Anand released before it. Hrishi kaku was adamant on an unknown face. Everyone in the unit felt awful about Amitji’s exit.

I was quite upset when I saw the rushes, Amitji was so good. I overdid this. I kept talking about it. Samir Bhanja, who replaced him, must have felt awful about the way I went on and on.

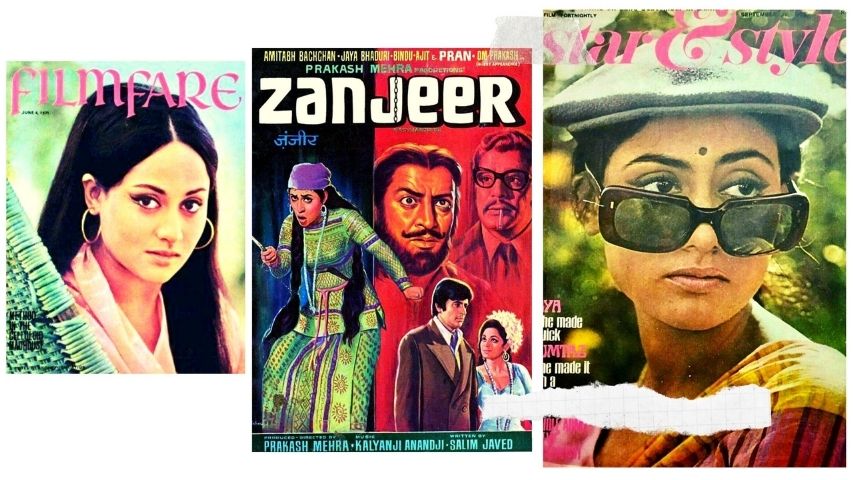

I felt you allowed Amitabh Bachchan to take all the scenes away from you in Zanjeer.

Why do you say that? Zanjeer was totally his film. I just played a street woman, a knife-grinder who turns into a sari-wearing docile sort after he brings her home. I wasn’t keen to do it because there wasn’t much for me to do. But Salim-Javed wouldn’t budge, they said trust us and I did.

Again in the climax of Abhimaan, you were studiously restrained.

I hate the business of one-upmanship with any artist. Only insecure actors try to steal scenes. A lot of actors I’ve known have tried to cover their co-artist’s face and shift positions to hog the frame. This used to happen at times.

Are you referring to Rajesh Khanna?

We were two very different people. We’re not competing anymore. He never spared me. But I have never paid obeisance to any actor. I never tried to convey the impression that “Tumhi ho maata, tumhi ho pita, tumhi sab ho.” On the other hand, if I like a person, I don’t have any qualms about striking up a conversation.

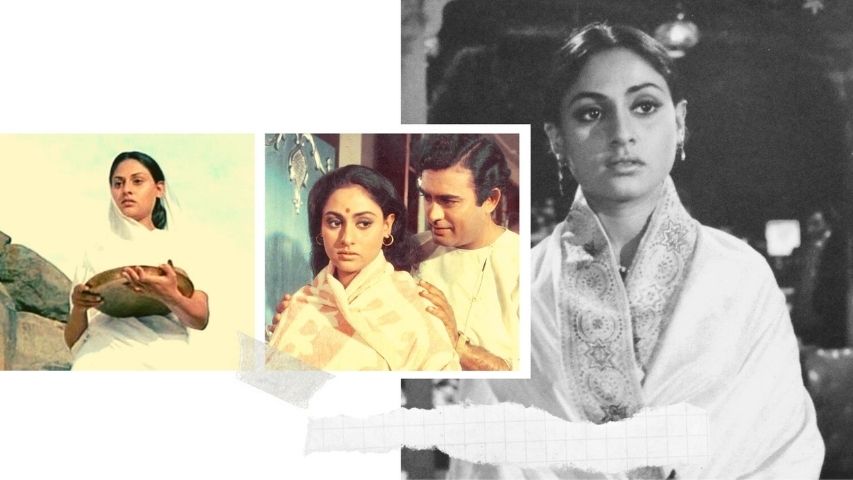

What did you learn from Sanjeev Kumar?

By acting with Haribhai, my sense of timing improved. You’ll notice a certain rhythm, a fluidity in many of our scenes together. After a few takes, I would tend to lose interest. I can’t go beyond a certain limit. Haribhai taught me that there are no limits, and to continue with retakes all day and night if it comes to that.

Neither Amitji not Haribhai would move away if they weren’t required for a scene. Occasionally, they would tell me, ‘wouldn’t it be nice if your said your lines of dialogue this way or that?’ with the director’s approval, of course.

Your films with Sanjeev Kumar were quite a mixed lot - from Koshish and Naya Din Nayee Raat to Nauker.

In Koshish I died so suddenly that I missed myself in the rest of the film. When I brought this up with Gulzar bhai, he fired me, “Why are you behaving like other stars?” He felt he couldn’t pamper me at the expense of the structure of the storyline. To that, I screwed up my face and said, “You are more in love with Haribhai than with me.”

Towards the end of his life, Haribhai seemed to enjoy wearing wigs and get-ups. He started changing his voice, suits and jackets for the heck of it. I guess all stars have this streak of exhbitionism about them. Naya Din Nayee Raat was not a great film, neither was his performance nor mine.

In Nauker, both of us were bound by the lines of dialogue and scenes we were given. We definitely tried to add whatever touches we could. Perhaps that’s why the film was long-delayed in production, the audience still found it quite fresh.

What are the kind of touches you have added to your performances?

Touches that have to be subtle, they shouldn’t cry out loud for attention. Like in Sholay, I didn’t have much to do. Yet somehow, I didn’t look out of place and made an impression. An actor shouldn’t stand out, a film should. Which is why I hate remarks like, “Arre, usne to uski chhuti kar di.” This doesn’t speak very well for the actor who has done the so-called “chhuti”. It’s an ego massage, not a compliment.

An actor must communicate with the audience without showing any effort. When it’s said, “Usne kya khoob acting ki!”, the actor has failed. Rather he should live the part, he should be and not do. But I’m afraid many of our actors want punchlines and heavy-duty dialogue-baazi.

Did you find it tough to do reaction shots - when the camera’s on you but the actor you’re reacting to is nowhere around?

I loved reaction shots. I prefer to listen than to speak. Hrishi kaku would vouch for this. Whenever he needed a filler shot, he would just say, “Put a quiet close-up of Jaya there.”

You’ve never talked about your experience of working with Manoj Kumar. That was quite a feisty role of a street acrobat in Shor.

Don’t ask me, he’ll tell you all you want to know. He’ll tell you I was a pain, that I gave him a lot of trouble, that I threw major tantrums. I’d rather not comment. Honestly, I did Shor because Hrishi kaku told me to. I was awkward, I lost sight of my role.

Okay, so how do you look back at Silsila?

If the climax was different, it would have been a pretty good film. It was quite a strong subject for Indian audiences when Silsila was released. Today it would be accepted because audiences have seen many more foreign films.

Back then, however, there were set opinions about how a wife and a girlfriend should conduct themselves. Also, the film was affected by too many rumours and gossip. Yashji (Chopra) doesn’t make films which depict real life. He keeps a base in reality and presents it in his particular style.

How much stress would you give to technique in acting?

Technique is necessary. Our newcomers have to compete with international performers now. People won’t go out to the cinema halls if they aren’t sure about a quality performance. So, right at the start, newcomers must learn how to walk five steps to the left, two steps to the right of the camera and so on. Once they feel at home with the lights and the lens, they can look within and draw the deepest feelings from their heart.

What about studying a role - or basing a performance on real-life observations?

No human being can cut himself or herself away from reality. On the contrary, an actor must think of three or four variations to enact a role. For instance, if he’s playing a beggar, he can combine all the observations he has seen on the street.

Also, one must be able to convey one’s state of mind - like I may be talking to you right now but I may be thinking of something else altogether. An actor has to be multi-channelled, the thoughts must be alive on different tracks at the same time. That will give him a naturalness, it will seem as if he exists.

He must use his life as a library, which stores information. The closest I’ve come to using my own experience was in Parichay, the girl was a lot like me. At the first narration, I had started forming an outline of the character. Then I did some homework, arrived at a psychological background for her and played it as if it was me going through all the various situations.

I wish directors would give actors more time to tap their inner strength. They give all the time in the world to the heroines to change their costumes. However, they don’t give them even a minute to wear their characters.

You played a blind woman in Aahat (adapted from Wait Until Dark). Was it tough-going to lose your sight before the camera?

I was apprehensive that I wouldn’t look blind at all. It’s much easier to play a character with physical debilities. I was young, restless and playful then. On my part, I tried to give the impression that the woman could see but there was no light in her eyes. They seemed dead.

Does acting facilitate coping with real-life situations?

No! For me it’s a completely different ball game to be a human being. I’d like to think I’m mature, controlled and understanding now. Yet there was a time when I was far too outspoken. I must have hurt a lot of people, and I do regret this.

Still, I can’t put on an artificial smile and say what I don’t want to. My insincerity is immediately noticed. I’d rather not lie in real life or in front of the camera. After all, cinema like everyday life should be all about nothing but the truth.

-853X543.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)