-853X543.jpg)

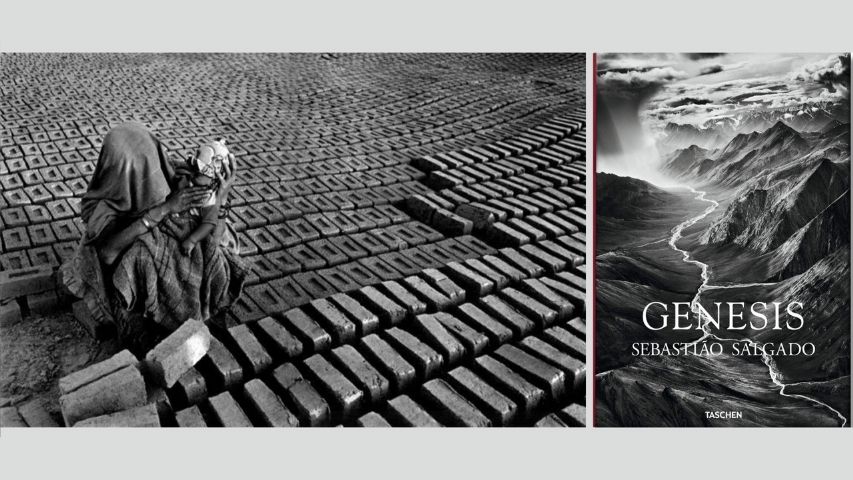

Of human bondage

by Khalid Mohamed December 28 2020, 12:00 am Estimated Reading Time: 7 mins, 21 secsKhalid Mohamed’s throwback to his encounter with social documentarist, Sebastio Salgado, whom he rates as the world’s most impactful living photographer today.

There’s something way superior about still photographs – unvarnished and unphoto-shopped – than the escalating number of videos and the limitless gimmicky visual inventions on the Internet.

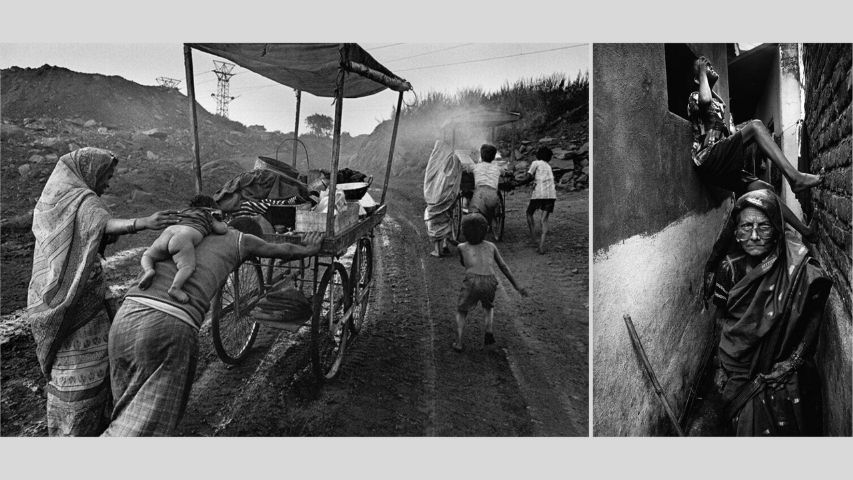

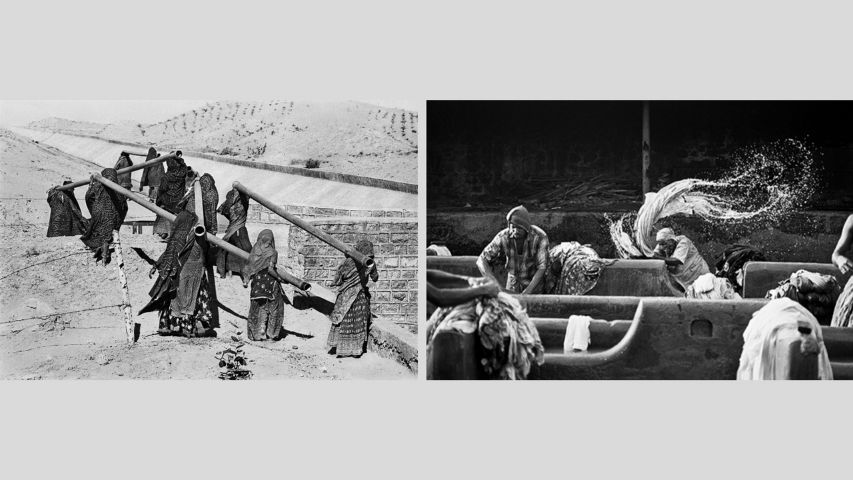

Indeed, Sebastio Salgado’s lacerating-stark, unmoveable images, dedicated to the limits of human endurance by the labour force and the deprived across the world, are not only a chronicle of our times but transcend themselves into an art form.

Speaking up with clarity about the subjugated section of the social stratae anywhere across the globe, the photographs avoid didacticism and carry a stamp of the camera person’s ideology. It would be facile to club this with any overt strains of Marxism though.

The ideology of the Brazilian photographer Salgado (now 76) is distinctly individualistic, it’s self-authored and relentlessly humane. Which is why whenever one feels a shred of self-pity for oneself, Salgado’s photographs can engage the viewer in an unspoken conversation. And they so many of them, contained in a series of voluminous books. The most striking one, being a 400-pager is succinctly titled Workers, first published in 1996 by Aperture.

Of Workers, the formidable American playwright Arthur Miller had remarked, “Salgado unveils the pain, the beauty, and the brutality of the world of work on which everything rests. This is a collection of deep devotion and impressive skill.”

_(10).jpg)

However, the greatest living photographer in my book at least, needs no endorsements. His life speaks for itself. From all accounts, Salgado, initially an economist, had fled from Brazil after the military coups there in 1964 and ’68 and subsequently settled in Paris.

Untrained in formal photography, after working for the leading agencies Sygma, Gamma and Magnum, along with his wife Lelia, he established his own company, Amazonas Agency, which would obviously give him an independent focus. He has travelled through over 100 countries. Some of his iconic shots have been devoted to the goldminers of Brazil and the global phalanx of migrant workers. Indeed, if he had been here to record the plight of Indian workers during the opening months of the pandemic, the results would have been nothing short of staggering.

The tall, gentle-faced, greyish-blue-eyed one-man force of nature, garbed in khaki cargo pants and shirt, was in India circa 1994. I was foolish enough not to realise then that here was a personality, whose oeuvre will forever be an invaluable legacy to the world. At that juncture, I was hooked to the seminal images created by France’s Henri Cartier-Bresson and Marc Riboud. The latter’s series on workers repairing the Eiffel Tower, at dangerously high altitudes, was as far as I had reached in grasping the might of world photography.

Salgado’s images are vastly different from those of Cartier-Bresson’s or Riboud’s. Unfortunately, they hadn’t reached my blinkered eyes. He had walked into the Filmfare office where I was employed, accompanied by the ace Mumbai-anchored, stubbornly low-key lensman Mahendra Sinh. They asked if it was possible for me to fix up a couple of hours to click a Bollywood shoot in progress.

Evidently, Salgado intended to capture the behind-the-scenes workforce, and not the popular stars. Off they cabbed it to Juhu where scenes were being picturised on Aamir Khan and Manisha Koirala. The next day, Sinh called me to say Salgado didn’t shoot any pictures, perhaps because everyone on location had become self-conscious.

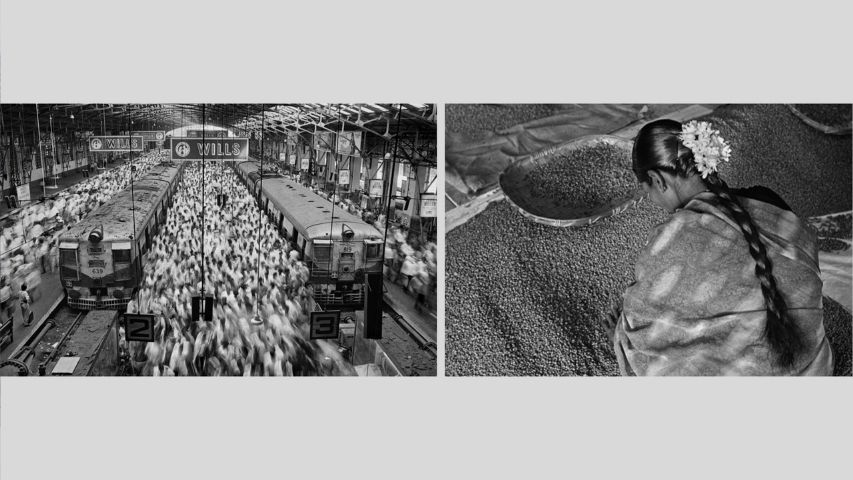

“Never mind,” Sinh added. “He’s happy just wandering around Bombay and photographing whatever catches his eye.” One of the unforgettable photos, in high-shutter speed, which emerged from his Bombay visit was of commuters spilling out of a local train at Churchgate railway station.

That’s that I thought, selfishly regretting the fact that I wouldn’t be able to persuade Salgado to part with a photograph of Aamir-Manisha for publication in Filmfare.

Fortuitously, coincidence was on my side. Next week, he was on the same Air France flight to Paris where I was travelling to interview the pioneering French writer and filmmaker Nelly Kaplan, the politically radical director Constantin Costa-Gavras, the charismatic actresses Catherine Deneuve and Leslie Caron, courtesy my friend Patrick Bensard who headed the Cinematheque de la Danse. My five-day schedule was already water-tight. Being an ignoramus, I missed out on the opportunity to interview Salgado on flight.

Converse with him I did, surprised when he hopped over from the flight’s business class to the gratifyingly half-empty economy class where I was seated. Travelling luxuriously wasn’t his scene, he preferred to downgrade himself, and talked about the Akele Hum Akele Tum shoot, which just didn’t yield any inspiring pictures. He flipped over a couple of Filmfare issues which I was carrying and politely said, “Glamorous, very glamorous, but why so much soft focus and artificial lighting?” We are like that only, I had to respond gingerly.

Towards the end of the flight, I handed over a box of dried fruit and sweets, picked up during the Diwali season. Overwhelmingly grateful, he insisted on dropping me in a cab right to the doorstep of Bensard’s where I would be staying. It was drizzling, the doorbell wasn’t being answered for a while, he wouldn’t leave before Bensard emerged at the door half-asleep. And before leaving, invited me to visit his studio if I could grab some time. Over the weekend perhaps.

The parquet-floor studio was enormous, requiring us to ride a mini golf car to reach the darkroom. There I was floored, hundreds of his photographs were being developed, and it would be the understatement to say they were stunning: candid images captured in diverse parts of India. “What do you think of them?” he asked tentatively. Couldn’t say a word, who was I to give my take on the superb images? Sensing my embarrassment, he changed the topic, “I know you have to meet Leslie Caron at her farmhouse restaurant today. It’s two-hours away. Have a coffee… a glass of wine… before you leave.” He had nothing to gain from me, and yet he was the epitome of humility.

That’s one encounter with the photographer with a ceaseless cause that I have never had the nerve to write about. It may have been brief and there was no q-and-a session for me to get into. Back home who would have published it anyway? Hence, I’m getting it out of my system today to salute an artist (a word he doesn’t approve of) whose images, in cumulation, sear the heart and mind. He doesn’t glorify his subjects, he doesn’t contrive that cliched ray of hope. Overridingly, he depicts the reality.

And that reality is the whole truth, a majority of his oeuvre being in black-and-white without faux technical intervention. He’s equally powerful in colour and in studies of nature, which infallibly describe the ravaged state of the environment.

A two-hour documentary on his work. The Salt of the Earth was made by the eminent German director Wim Wenders and Salgado’s son Juliano. It won a special jury award at the Cannes film festival, nominated for the Best Documentary at the Oscars, besides winning top trophies at the San Sebastian International Film Festival and at the Cesar Awards. Truly suggest that you watch it on YouTube (yes, it’s accessible there).

Salgado’s purpose isn’t activism or denunciation. The language of photography for him is a way of life, an unspoken ideology. From his interactions with the world press, I quote, “What I want the world to remember are the problems and the people I photograph. What I want is to create a discussion about what is happening around the world and to provoke some debate with these pictures. Nothing more than this. I don’t want people to look at them and appreciate the light and the palate of tones. I want them to look inside and see what the pictures represent, and the kind of people I photograph.”

Another quote, “I try with my pictures to raise a question, to provoke a debate, so that we can discuss problems together and come up with solutions.”

That’s Sebastio Salgado, the greatest living photographer, I have had the privilege to meet, albeit by chance. And learn the life-lesson that a photograph can be mightier than the proverbial sword.

Photographs Copyright: Sebastio Salgado

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)