Lost but not found: An artist focuses on the tragedy of the Nation’s rising cases of Missing Children

by Khalid Mohamed August 7 2018, 5:11 pm Estimated Reading Time: 4 mins, 41 secsAt a modest estimate, a lakh, if not more children go missing every year from diverse parts of the nation, including the top metros Mumbai and New Delhi. According to the National Crime Records Bureau, of these 60 per cent are minor girls.

How many of the children - abducted, trafficked into the flesh trade, sold and abused in the market for organs - are traced eventually, remains in the realm of guesswork. Statistics on this rampant crime are sketchy at best.

A sizeable section of the gone kids are runaways because of dire poverty. Moreover, the incidence of street children in the metropolitan cities -- vulnerable to exploitation -- is in a count of a fast-multiplying number of hundreds of millions.

I cite these statistics - or what’s accessible of them - as a preamble to introducing the itinerant 37-year-old artist Amit Kumar Shrivastava, who travels between his hometown Gwalior and New Delhi. Currently, he is also engaged in a handicrafts project with a gallery in Kathmandu.

_thedailyeye.jpg)

Artist Amit Kumar Shrivastava

Significantly, his prolific oeuvre of artworks has sought to spread awareness about the malaise of the disappearing children which shows no signs of a let-up.

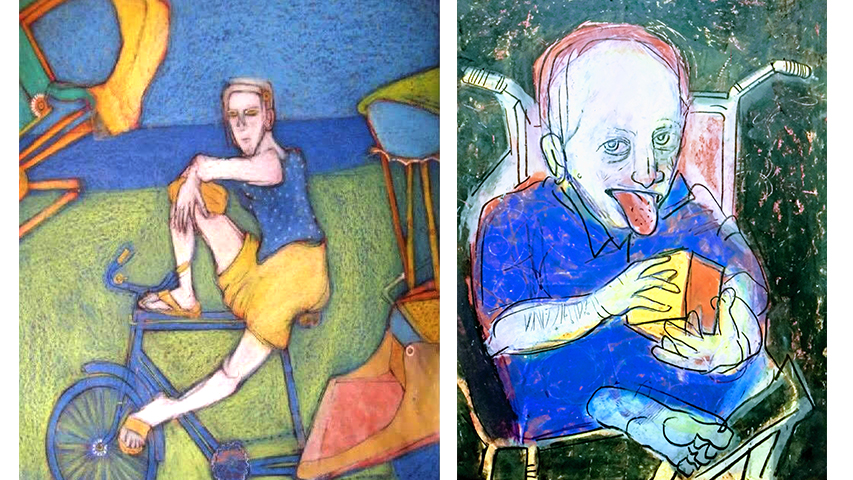

Shrivastava’s series on missing children, since last year, has commanded attention at various art shows across the country. The series comprises 30 sketches of lost children, done in oil pastels on pastel sheets. More are in the works, in acryclic on canvas.

“It’s a misnomer that viewers are only drawn to comforting and pretty images,” he states, adding. “The response towards the series has been consistently supportive… and I’m not only talking about corporate backers. Individual collectors go for such artworks since they know the funds will contribute towards a cause.”

The artist elaborates, “ I know that the images cannot in any which way resolve or mitigate the menace of kidnapping and enslavement of kids. My effort doesn’t even amount to millimetre of a drop in the ocean. Yet, an artist’s responsibility is to bring issues into sharp focus.”

Declaring himself ‘apolitical by nature’, Shrivastava maintains that any form of social comment can serve as a wake-up call. His paintings have been frequently sourced from photos of missing kids, printed in newspapers or beamed by a few television channels (Doordarshan in its incipient years, would feature these regularly).

Lost Childhood

On the street walls at traffic junctions of even Noida and Gurgaon on the outskirts of Delhi, black-and-white ‘laapata’ posters are commonplace, he points out. More often than not the print, Internet and TV media don’t yield any clues. The already overworked lawforce is left bereft of any leads to the possible whereabouts about the kids who have vanished into a limbo. Are they still alive or are they dead?

“Through art,” Shrivastava states, “it has been possible to connect with real stories and also with strangers, like someone I have seen from my home’s window. When I saw a middle-aged man suffering from Down sydrome being wheelchaired by his aged father, I had to ask myself, ‘What will happen to the man when there’s no one attend to him?’ Then there are stark moments which I have sought to express. Like a bicycle rickshawala of Delhi who would spend hours waiting under the scorching sun for fare. The recession of 2011 had affected every strata, particularly the working class whose anguish had to be captured.”

Waiting for a fare Down, Not Out

Although his cause-centric artworks appear to be his forte, Shrivastava concedes, “I have no pretensions about being a reformist. I have to earn a living like everyone else. There are times when there’s a spurt in the demand for my work. And there have been times, when there been a lull.” To stave off lean days, he takes on assignments on commission, be it the installation of a clock in Delhi, or moonlighting in the domain of computer graphics and animation.

Studying Strangers

His father R.P. Shrivastava, a retired employee of Public Works Department, wasn’t exactly enthusiastic about him venturing into an area where security is often a question mark. With scepticism he allowed his son to graduate in Fine Arts from the Indira Kala Sangeet Vishvavidyalaya in Chhatisgarh. “Of course, he’s proud of me today,” the son smiles with relief. His elder brother Manish is a software engineer while his twin brother Sumit is with the Air Force.

“But for that zid of mine to travel a different route,” the artist narrates. “I’ve been a good boy, and agreed to an arranged marriage as soon as it was suggested to me. My wife and I have a five-year-old daughter, who incidentally, seems to be pretty good at drawing and sketching.”

“How much of a child still resides in you?” I ask Shrivastava. After the longest pause, he answers, “I’d like to think of myself as a responsible adult now, but unfortunately a helpless one. Every time I see a poster of a missing child staring at me in the face, my heart skips a beat.”

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)