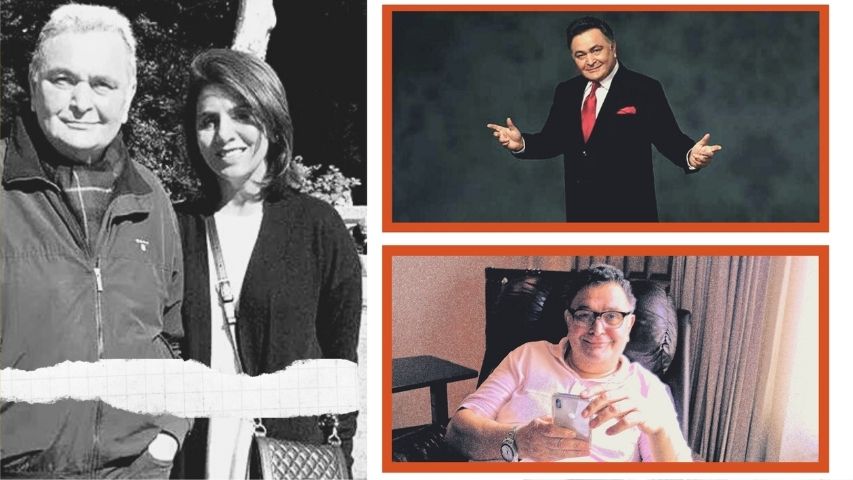

Khalid Mohamed remembers the super actor and always-supportive friend, Rishi Kapoor, on the event of his first death anniversary.

Over a year of the pandemic has flown by turbulently, still wrecking incalculable tragedy in its wake. As we deal with our mental anxieties and more, I miss my dear dear friend who would have been just a call away to yell at me, “Chill idiot, you are not alone.”

Rishi Kapoor passed away at the age of 67 on April 30, last year. I achingly miss my Chintu, who in recent years showed up in varied shades of roles topped by terrific performances in especially Do Dooni Char, Agneepath, Aurangzeb, D-Day, Student of the Year, Kapoor & Sons and Mulk. He was pleased as Punch. The tables had turned after a phase of lay-off when no hefty filmmaker would drop by at his KrishaRaj bungalow on Pali Hill.

He was back up on the marquee where he belonged. At the same time, without making it obvious, he would worry about where and how the career of his son, Ranbir, was going (vis-a-vis Bombay Velvet he’d just make a wry face without commenting). He had surrendered to the idea of his commodious home, with a sunken garden and a tastefully-appointed den for guests, being developed into a high-rise.

Separate floors in the under-construction tower would be assigned to Neetu and himself, to Ranbir and his parentally-approved Alia Bhatt, and his Delhi-based daughter Riddhima. Till it was ready, he had moved to a nearby penthouse. He’d chortle about the building’s name, Wit’s End, lodged in one of the slimmest gullies on the nearby Hill Road. “The entrance is weird,” he’d laugh some more. “But come on over, you’ll like the place. And I’ve kept a bottle of wine chilled for you. Not to fuss, it’s St Emillion from Bordeaux or wherever, it’s expensive and exclusive.”

On our last evening, which had clocked on to 2 a.m., when I usually turn into Cinderella, he had news for me that would make the front pages. The iconic R.K. Studio was being sold off to developers with the consent of the entire Kapoor family. A fire outbreak had gutted an extensive section of the age-old studio; the R.K. memorabilia, mementoes and memories had been burnt to cinders. “What’s the point in holding on to it now?” he had asked regretfully, “You know we Kapoors are extremely sentimental but we have to be practical.” So far, the developers have preserved the beautiful entrance to the studio with the R.K. insignia.

Although the lighting in the house was dim, I’d insisted on clicking photographs of Rishi. By the way, he wouldn’t like to be addressed as Chintu - “What kind of name is that for a grown-up man?” he’d scowl.

Far too accustomed to Bollywood courtesies, I’d call him Rishibhai. “Anyway, why do you drink that pissy wine? Kuchh aur piya karo. That’s a lady’s poison, not yours”, he had hectored me and asked about the progress on the stage play, Rishi and I had written together, part of it during his off-hours on the shoot of Kapoor & Sons in the calming environs of Coorg.

Initially, the National Centre of the Performing Arts was to produce the three-act musical play and stage it on their premises. However, despite the rigorous rehearsals for Rishi, which was based on his unrequited love story with a girl from the Cathedral and John Connon School, before Bobby made him a huge star overnight, the budget sanctioned was just not sufficient.

Rather than hack out a mediocre play, which wouldn’t do justice to Rishibhai’s slice-of-life, I had begged off from the NCPA. Other sponsors had their own bedevilments, like an event management agency which assured me that the play would be premiered at Baroda, under the aegis of the Gujarat state government and then taken cross-country. Cool. Problem ahead: the state minister who had sanctioned the production as part of its annual cultural festival, was either sacked or transferred. The event agency never got back.

Next: Rishibhai organised coffee meetings with other funders, including one who had this strange notion of creating the play with 3-D effects. Being no Spielberg, I had to decline. And the script’s co-author and pivot huffed, “Maaan, you’re too fussy. I’ve seen your Fiza and I did do a guest appearance in your Tehzeeb, didn’t I? You’re a director, yaar, stop pen-pushing, bahut ho gaya.” Incidentally, Rishibhai was the only living soul to detect the director in me categorically. A scant few of my other friends had politely too - forget the legion of thumb-downers. For giving me that confidence shot, I will be forever indebted, and that’s an understatement.

After that meet, he would be busy at shoots. And then the shocking news broke that he had to be rushed to New York for treatment for cancer. He couldn’t be there for his mother Krishnaji’s funeral, or it would have been too late. I can imagine how that must have devastated him.

For over a year in New York, supported like the proverbial pillar of strength by Neetu Singh Kapoor, he was on the mend. Occasionally, he’d WhatsApp from N.Y. that the prolonged intervals between the procedures were making him restless. Fortuitously, he was finally declared fit enough to return home, and to work. “Must meet and catch up soonest,” he had messaged. That was to be soon after he had completed his scenes for a film in wintry Delhi, where he complained of feeling uncomfortable. The medical treatment resumed, the Coronavirus struck, and just like that, without any last words, Rishibhai had gone. Naturally, mainly his family was permitted to attend his final rites.

Throughout, Rishibhai was aware that he was an extraordinary actor but had never been given his just dues. He’d often bring up his performances in Damini and Saagar, which were underappreciated, because his co-stars had the more showy, script-boosted moments. That he’d snagged a Filmfare Award for Bobby, he had no compunctions about admitting that the trophy had been “bought”. When he was garlanded with awards galore for his latter-day performances, there was still that element of dissatisfaction, and an abiding cynicism of the award rituals.

Since his first go as a director with Aa Ab Laut Chalen didn’t click, he was wary of venturing back to the terrain. A pity because he was an astute technician, instantaneosly vocal when a shot was being taken brilliantly or clumsily. Once, he had chatted excitedly about a script, which was about a woman activist, essayed by Vidya Balan, campaigning for the construction of public toilets in remote villages. He was to play the road-block in her mission. A few weeks later, he rued the project wasn’t happening. Was this script later reworked as the Akshay Kumar showcase, Toilet: Ek Prem Katha? I’ll never know.

In addition, there was this Sudhir Mishra project pitching him versus Amitabh Bachchan as rival aristocrats, now bickering over a woman in their past. And if Manoj Bajpayye had called him up for a medium-budget project, he was totally gung-ho. A fortnight later, he had lambasted me, “What’s with this Bajpayee chap? I had given my okay but he never got back.”

Clearly, Rishibhai was open-hearted to the point of being one of a kind. He’d delight in returning to the locations in Shimla where he did his first shoots, his room at Wit’s End would always be playing vintage songs through hidden speakers.

He had thousands of stories to tell, to mock himself self-deprecatingly. Heartbreakingly after we had finished the first draft of the play Rishi, he had requested, “Just make sure Neetu emerges as the strong, superior heroine. We may have had our differences but believe me, she’s the only woman I’ve ever loved and I promise I always will till my last breath.”

Rishi Kapoor, always a man of his words, kept that promise.

-853X543.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)