Lights Still On: Portrait of a 70-year-old Photo Studio where once Bollywood’s Legendary Stars Shone Bright

by Khalid Mohamed July 4 2018, 6:00 pm Estimated Reading Time: 5 mins, 52 secsThe incalculable number of photographs – running into crores – of vintage Hindi cinema’s charismatic actors and film classics have vanished into thin air. Lovingly lensed by anonymous as well as ever-remembered lensmen, the photos have been either shredded or are rotting away somewhere out of sheer apathy and neglect.

The scant few original photo negatives, especially of Dilip Kumar, Raj Kapoor, Dev Anand, Madhubala, Nargis, Meena Kumari and Suraiya, needless to say, are priceless. The vestiges of the 1950s are accessible to a degree.

The ethereal Madhubala in Mahal

As for the visual chronicles of the silent era as well as the mid-1930s and ‘40s, these are heartbreakingly blotchy and oftentimes mere digitised copies uploaded on Internet from newspapers and magazines of the era.

Vis-a-vis Bombay’s majestic photo studios which were once assigned to photograph star portraits and publicity pictures from the studio sets, they have all shut shop.

The Hamilton Studio at Ballard Estate is lored to be the oldest one of its kind with a treasure trove of images, especially of the erstwhile royalty, the aristocracy and film stars. The India Art Studio at a traffic junction on Kalbadevi, excelled in family group portraits. Both the studios from the bygone era have withstood the test of time.

And on the main artery of Dadar, the distinctly old-worldly Indian Photo Studio -- once assigned to photograph exclusive star portraits and film publicity pictures -- lives on, just about breathing on an oxygen tank.

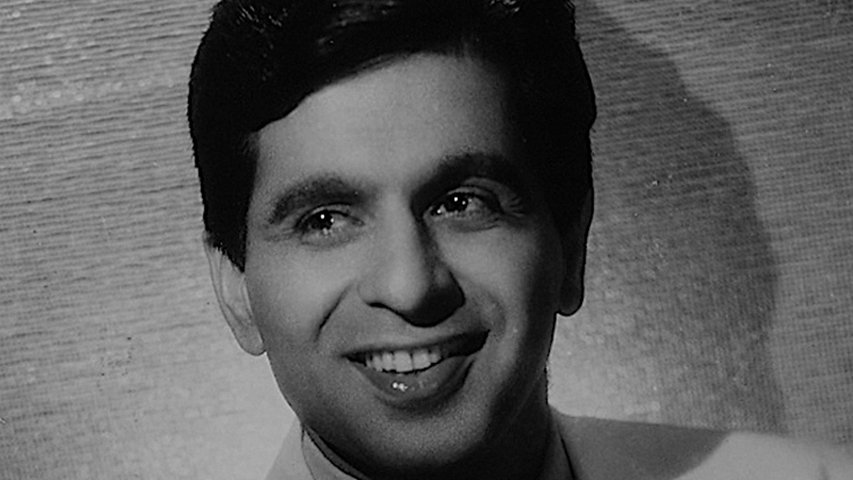

The actor for all seasons, Dillip Kumar

The spacious photo studio was founded in 1948 by the late Jethalal H. Thakker, famed for his black and white portraits, caressed by shadow-play lighting.

Sporadically a section of Jethalal H. Thakker’s estimable oeuvre has been exhibited at packed shows down the years at the galleries of the National Centre for the Performing Arts (1993), the National Gallery of Modern Art (2000) and the Bhau Daji Lad Museum (2015-16).

Since the shows have not been cost-effective, the entire Thakker chronicle -- in silver gelatinous originals -- of Bombay cinema during its golden age, is now up for sale.

Vimal J. Thakker, son of the late photographer, says stoically, “A prestigious institution devoted to the preservation of Indian culture and cinema has expressed an interest in the whole lot,” adding, “I’m 65 years old. My father had told me that every drop of blood and sweat of his is invested in the studio. He wanted me take the legacy forward. But frankly, I’m not as accomplished as a photographer as he was. I guess, I’m caught in a Catch-22 situation. It’s stressful to keep it going, neither can I sell it.”

When the eyes speak, Raj Kapoor

The studio which has preserved its art-deco interiors, antique furniture, rows of light bulbs, and a patterned trellis door which would frequently serve as a backdrop for the portraits, has had to adapt to the times. Families still trickle in for group photographs and passport snaps. Digital restoration of mottled pictures from family albums are undertaken to make ends meet.

If he can’t move from the studio, situated on Dadar’s Plot No 200, once known as the Bombay Garage building, Vimal J. Thakker shrugs, it’s because, “We’ve been tenants here, not proprietors. The costs of maintaining the studio are rising, but not our business. There are months, when we just about get by.”

The Thakker patriarch, Jethalal, had migrated from Karachi during the partition. When he first arrived in Bombay, he had to rough it out by sleeping on the streets of the Colaba

Causeway. He moved to Lonavla and then returned to Mumbai, locating a home in the central suburb of Sion.

That certain smile, Nargis

Employing his experience as a civilian photographer for the British army in Pakistan, Jethalal began clicking photographs. The portaits of Nalini Jaywant, who lived in Matunga then, close to Sion, caught the eye of the movie moghul A. R. Kardaar who hired him to shoot stills for his films Dard (1947) and Dulari (1949). The Kardar-Jethalal collaboration lasted right till the Dilip Kumar-Waheeda Rehman starrer Dil Diya Dard Liya (1966).

“But Kardar saab owed quite a substantial amount of money to my father,” Vimal recalls with a touch of amusement. “When Kardar sold some of his films’ rights, he needed photo-sets. I must have been a teenager but I wouldn’t hand over the material. I went over personally to his house on Marine Drive and said ‘nothing doing’ till he finally handed over a bearer cheque. Film people would often dilly dally with the payments. So, I became my father’s accountant in a way.”

Jethalal H. Thakker favoured studio shots over candid and natural lit images. Among those who trusted him implicitly to make them look enigmatic, there were the triumvirate of Dilip Kumar-Raj Kapoor-Dev Anand and practically all the leading ladies of the time right till 1968. His last photo-shoot was of Madhuri Dixit, accentuating her eyes, for a film trade broad-sheet.

Hats off, Raaj Kumar

“My father had become disillusioned with the film industry’s production system,” Vimal elaborates. “He was very fond of Sunil Dutt though. Dad would always attend the New Year’s eve celebrations hosted by his production company, Ajanta Arts, at Dutt saab’s bungalow-cum office in Bandra. The still of Dutt saab and Leela Naidu used for the poster of Yeh Raaste Hain Pyar Ke (1965) was composed and shot by dad.”

Jethalal H. Thakker was the first one to click photographs of Raaj Kumar, who continued to call for his favourite lensman at his shoots. When his son, Puru, was about to join the movies, the actor insisted that no one else would shoot him for his first session but the photographer who had relaxed the jaani before the stern gaze of the camera.

Today, Vimal J. Thakker at the India Photo Studio

Following an accidental fall 15 years ago at his Sion residence, Jethalal H. Thakker passed away at the age of 80, entrusting Vimal to keep the studio going, no matter what. “I’ve tried to do my best but my best is not enough,” says Vimal emotionally. “My two daughters are married and settled in London. Lately, they cajoled me to get myself a decent car.”

On a Sunday afternoon, footfalls are slack at the India Photo Studio. The rush is on at the studio’s adjoining Chitra cinema hall, where ‘Sanju’ is playing to packed houses.

“Moviegoers still step in to see our old cameras and portraits on display,” Vimal concludes. “But in the cellphone age, everyone’s into selfies. And today’s stars like to see themselves more on Instagram rather than on portraits which last a lifetime.”

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)