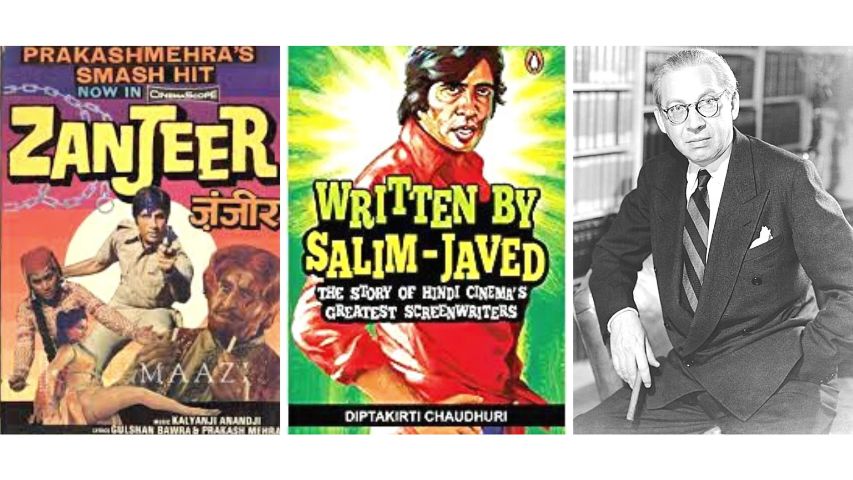

Ranjan Das takes the Diptakirti Chaudhuri account, Written by Salim-Javed, as a case in point to explore a vast hyperlinked universe, which the book led him to explore.

In Diptakirti Chaudhuri’s deeply engrossing account, WRITTEN BY SALIM-JAVED, Salim Khan quotes Alexander Korda on the brevity that should go into dialogue writing, “Film dialogue is like the poor man’s telegram.”

Anybody with an iota of interest in Hindi cinema would know that the Salim-Javed duo had revolutionized Hindi films of the 1970s with their taut screenplays and crisp dialogues that have since attained iconic status and have been etched into the memories of successive generations of film-goers. They were the first to bring into prominence the importance that a screenplay plays in a film by having their names emblazoned on film posters alongside stars and directors and demand pay checks that equalled - and sometimes surpassed star payments. They were brazen marketers.

Never to claim originality, Salim-Javed always acknowledged their sources of influence; their ability consisted in rehashing the original to make them contemporaneous. In this, they were master craftsmen. They skilfully adapted the Spaghetti Western Death Rides a Horse (1967) twice – Zanjeer and Yaadon Ki Baaraat, both released in 1973!

In a non-fiction book such as this, there is always a chance that the curiosity of the reader gets tickled and he becomes interested to know more about the specific sources and influences that worked on the protagonists, i.e., Salim-Javed. The Spaghetti Western (Westerns made in Italy by Italian technicians and directors, starring Hollywood stars) mentioned in the book would surely lead to a sudden spurt in torrent downloads of the film, leading in turn to a comparison of the original with the two derivatives; similarly, a newer generation of film buffs might want to revisit the film that triggered Sholay - John Sturge’s The Magnificent Seven (1960), which in turn was inspired by Kurosawa’s classic The Seven Samurai (1954).

Alexander Korda, whom Salim Khan quotes on dialogue writing evokes similar curiosity. The name, despite sounding familiar, fails to figure in the immediate pantheon of world-renowned masters; but since this casual, but pertinent reference to the man is alluded to, one is tempted to look up the internet for more information about him, and what one stumbles across is phenomenal.

Alexander Korda (1893-1956) was a Hungarian-born British film producer and director. Born into a Jewish family, his filmmaking career spanned Hungary, Austria, Germany, Hollywood and eventually Great Britain, where he became a leading figure from 1930 onwards. In a career spanning four decades, from the silent era to sound films, he directed 68 feature films and produced 57.

Considered as the greatest British movie Moghul, he was knighted by the British government in 1942, and the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, as an homage to him, instituted a category called Alexander Korda Award for the “Outstanding British Film of the Year.” Film buffs who are otherwise unfamiliar with Korda’s contribution, would best remember him from Carol Reed’s cult classic The Third Man (1949), starring Orson Welles - his name appears in the credits of the film as the producer, along with the director.

In the process of inquiry into Korda, some more interesting facts emerge about his life. While working in Hollywood, during the transition phase from silent to sound films, he divorced his first wife, a Hungarian actress named Maria Corda, because she could not adjust to the new technology due to her thick English accent. Talk about professional life affecting relationships, and here we have a ruthless example.

As the curious mind prods along, delving deeper into the net, more facts emerge, this time about his second wife Merle Oberon, a British film star whom he married in 1939 and divorced six years later. (He was married thrice.)

Merle was an Anglo-Indian, born in Bombay in 1911. She worked as a telephone operator in Calcutta before migrating to the UK in 1928 at the age of 17 where she got into films. Her career got a major boost when she was spotted by Korda and was cast in The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933) opposite Charles Laughton. She was nominated for the Best Actress Academy Award for her role in The Dark Angel (1938) and had several affairs, including David Niven, and later John Wayne, even when she was married to Korda. Amongst other films, she is also remembered for her role in Wuthering Heights (1939) opposite Lawrence Olivier.

Throughout her adult life, she claimed that she was born in Australia in order to conceal her Indian roots. The year before she died in 1979, she finally admitted her true origin.

Such is the hyperlinked world that a good non-fiction book encourages its readers to navigate, plunging them into depths that swarm with forgotten nuggets of history.

-853X543.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)