-853X543.jpg)

FESTIVALS: THE LOKHANDWALA STREET-CORNER START-UPS

by Siddharth Kak April 14 2024, 12:00 am Estimated Reading Time: 12 mins, 59 secsToday, Siddharth Kak explores the by lanes of his neighbourhood to discover a variety of Indian food and snacks on offer by a unique range of start-ups founded by some of the most humble people you can find on mother earth.

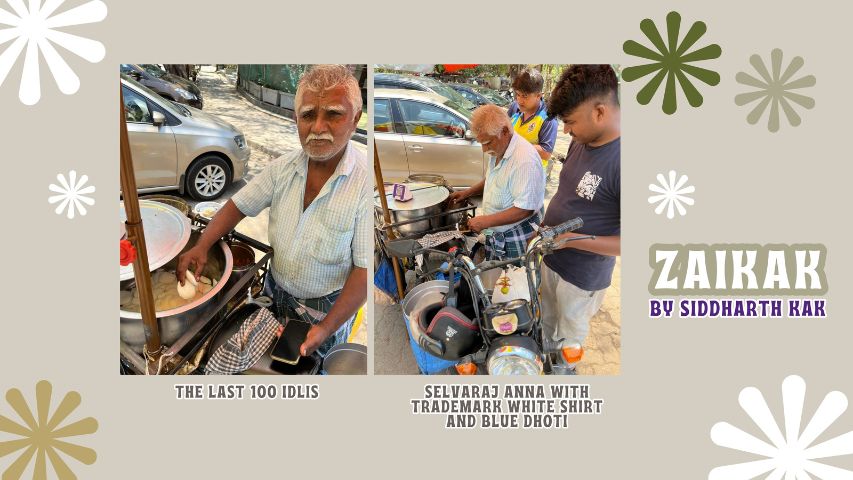

Let me tell you the story of Selvaraj Anna who came to Mumbai, then Bombay, the city of dreams, to earn a living when he was just a teenager, from an impoverished household in Kanyakumari. He worked as an assistant in a kirana firm for 20 years, and then started his idli business before returning to Kanyakumari and leaving his nephew Muthukrishnan to take his place at the Lokhandwala street corner that he occupied.

After two years of a struggle in Kanyakumari, Selvaraj returned to Mumbai where had struck lucky, to begin anew. A self-made man, he is now 65 years old. His daughter stayed back in Kanyakumari and is married there. His wife Parvati and he live in a single room chawl in Bhagat Singh Colony, Goregaon. For the last 25 years he has been visiting the Lokhandwala Circle near my home every morning to sell his Idlis, medu wadas, dosas and dal wadas by the dozens, even hundreds, from 7 am to noon every day. It doesn’t matter if it is a holiday or a working day.

From early morning, the locals, the rikshawallas, vendors, the dog walkers, the milkmen and watchmen, and the students from the medical school, residents in the neighbourhood, early morning worshippers from the nearby Gurudwara or namaz worshippers from the nearby mosque, literally scores surround his portable bicycle shop with an umbrella fixed once the sun comes up, as he scoops non-stop hundreds of soft fluffy Idlis, scores of dosas and medu wadas, slapping a generous helping of sambar and coconut chutney on each overflowing paper plate. There is no sophistication here. No paper spoons or filtered water bottles. You eat with your hands and the combination is delicious. Everything is available at one price ₹20 plate. For that you get five Idlis, five medu wadas , or two dosas. It is a hearty, inexpensive snack.

By 10 am, his stock starts getting depleted. Finally by about noon all that remains in his huge round utensil is the last layer of about 100 idlis. How many Idlis does he make every day? Even he doesn’t know. All he knows is that when this huge utensil is full he has enough for the day. I estimate 700/800 idlis. Prasad, a regular, who worked distributing newspapers for a local vendor, hazards that there are over 1000 idlis in the utensil. It doesn’t matter. By 1 o’clock it is all finished.

Selvaraj’s clients start arriving early in the morning. School children rushing to school, pausing for a snack to start the day. Office going staff waiting for a lift or a taxi. People going for a walk stopping for a little healthy snack . Next door, a coconut vendor will quench their thirst. Maids hastening to their work in high-rise towers take five minutes off for an inexpensive bite.

Residents of this well off neighbourhood, stepping out for chores like young Arnab of Highland Park passing by at midday for a haircut next door. The idlis are now over. Still he is ready to accept even the second last plate of squashed wadas, because perhaps the coconut chutney and sambar are so tasty. Within minutes, two young girls, Mayuri and her friend, sales girls going for their shift at the nearby popular Society Stores have the very last plate of squished wadas packed, though the sambar has run out. Still, there is the delicious coconut chutney for which they get an extra dollop.

India is a land of innovative start-ups. Expensive market research leads to product discovery. Complicated financial planning leads to price setting. Expensive investments lead to the right location for distribution.

At Lokhandwala Circle, one discovers the beauty of India’s Jugaad. Selvaraj and his colleagues have instinctively found the right place, which is all about location, location, location. Common sense helps them set a price which does not give even a humble passer-by much pause for thought. Just ₹20 per plate. Nothing complicated. There is no complication of choice either, no menu card, no visiting card, no placard, no pamphlets or publicity. The trick is that they must retain local goodwill so that they continue to hold their spots and also bring in their product well under ₹20 a plate so that some profit can be earned. In order to do that, they cannot afford to hire staff, so it is a family enterprise, just husband and wife. It is a precarious living, but they have their dignity.

Let me see. If Selvaraj sells about 200 plates a day he probably earns about ₹4000 before he packs up. Now he has to buy the ingredients for the dough, the expensive oil for frying. In the evening, the cycle begins again. He has to make the dough and then, along with his wife Parvati, from midnight he begins steaming the idlis and frying the wadas and dosas, non-stop so that he reaches his 700 or 800 figure or whatever fills his utensils to the brim. Then he sets out at 6 am with his travelling shop firmly strapped on to a specially mounted iron tray, so he can reach the Lokhandwala Circle by seven and put up his portable stand.

After 11 the nature of his clientele changes - now those finishing their morning shifts, washing and cooking bai’s like Roopak, drop in after their morning schedule to grab a healthy snack before going back to look after their own homes. The hustle bustle continues till the hot sun forces people indoors.

Selvaraj has no insurance. He has no staff beyond him and his wife Parvati. If he falls ill, he has no earning for that day. It is a rough and brutal life, but one with which he has come to terms. He is not an educated man. He cannot make a living any other way. Perhaps he has been able to put aside a few hundred rupees a day in the last few years, to tide him over retirement or illness. He plans to go back home to Kanyakumari from where he came, to spend the last of his days.

But now he works diligently with an unfailing smile, endlessly serving the orders of the constant hungry cluster around him preparing each plate with robotic dexterity, a hundred times a day. He offers his services calmly and humbly. It is people like Selvaraj that give me pride in being an Indian, faith in the qualities of humility and hard work that constitute the lot of the average Indian.

For 25 years, Selvaraj who is short and stout, has pedalled his way down from Goregaon on a bicycle weighed down front and back with the parasol and the huge utensil full of idlis strapped onto the back of the cycle, with cans of wadas, and bags of extra sambar and coconut chutney, dangling from the handlebars. You need strength to cycle with this weight, from Goregaon to the Lokhandwala Circle, a distance of about 10 km in the early morning, every morning, and then stand continuously serving the people for five hours till finally it is time to heave a sigh of relief, having managed to sell all he has cooked. Then he must cycle back 10 km to his one room chawl in blazing heat or rain, to sit at last for a simple lunch cooked by his wife, indulge in some conversation, a brief nap, a bath and then begin the cycle all over again as evening falls. While we are relaxed watching TV at night, or the IPL, or some exciting melodrama on an OTT channel, Selvaraj and Parvati are busy.

Like a human conveyor belt, they are preparing for hours the soft and fluffy Idlis, and crisp wadas, without missing a beat. Try it for two days. You will get tired. Very tired. Selvaraj and Parvati have been doing it for 25 years and perhaps that is in their future too for the next few years while he still has the strength to make and deliver.

In between Selvaraj Anna took a break and left his nephew Muthukrishnan to occupy his spot. Muthu managed but he did not have Selvaraj’s panache. Still he hopes for a better future sending his son and two daughters to school and continues to pitch his stand next to his uncle’s, even after his return.

What does karma have in store for Selvaraj? Duty and devotion without contemplating reward? He is following the Bharatiya dharma. But what does the country do to help and support marginalised self-made entrepreneurs whose life and discipline are the heartbeat of India? How are we helping them to prepare for old age and health? Do we feel absolved of responsibility by giving them ₹20 in exchange for a plate of idli and sambar? Selvaraj does not eat a morsel for the five hours that he stands and delivers his vittles. He has no time to answer calls.

But yes, he has a phone. Two months ago he bought a TVS motorcycle from his savings. At age 65 he does not now have to pedal 10 km each way anymore but he continues to live in a single stuffy room with bare amenities and a fan that whirrs endlessly, like the cycle of life itself. But in Kanyakumari, where his married daughter continues to live, he has, through dint of hard work, been able to invest in a couple of rooms in a chawl, which he gives out on rent.

His nephew Muthukrishnan has not yet graduated from his bicycle, but he has been practising only for the last few years.

Selvaraj reminds me of an assistant who joined me 40 years ago when I began my film production company Cinema Vision India. Peter, like Selvaraj, came to seek his fortune in Mumbai from down South as a teenager and began life as an assistant worker in a flour mill. Peter was barely 5 feet tall and dark complexioned, but by the time he finished his evening shift in the flour mill, he appeared like a white ghost. One day he wandered into my office and asked for a job. I had just begun Surabhi and I needed help. He became the official dogsbody, running errands, making tea and eventually became an enthusiastic production assistant who worked with me for 30 years, before he retired to do charitable work in his school and church. While working for me, he became one of the lucky few who won a World Bank funded slum redevelopment lottery for a flat, from among several hundred thousand applicants in Mumbai. It was a one in a million chance. He was delirious with excitement. We were overjoyed at this miracle that changed the fortunes of a desperately poor, illiterate lad among the vast multitudes in then Bombay. He was able to leave his tenement in the Santacruz Golibar slum and move to his own flat where along with his wife Nirmala, he brought up his family. When eventually he passed away, he was known to the entire team of Surabhiwalas in India as Peter Sir.

What will Selvaraj be remembered as? One day the place that he somehow found for himself at the Lokhandwala Circle will fall vacant. Selvaraj will have gone home or perhaps to a better place. Someone else would occupy his space selling something else. Or perhaps his nephew Muthukrishnan will continue his legacy till Muthus son and two daughters grow up and free Muthukrishnan from years of drudgery.

Selvaraj will one day be forgotten. But for now can we help make his living years better, give him and his family some insurance for the future? Selvaraj has allowed me to use his telephone number in this feature. So if any of you wish to contact him and place bulk orders of idlis and wadas for breakfasts or lunches call him on +91 80979 77354 or visit him between 7 and 11am at his Lokhandwala Circle motorcycle umbrella outlet. Perhaps someone might advise him how to distribute his products better or even start an online service, creating more substantial savings for his old age. I’m sure he is a wise old man and in all these years he has learnt to differentiate between genuine and fake. It shows in his clean food and it is implicit in his clean temperament. Selvaraj has survived all these years, but we can perhaps help make the rest of his years better..

The story of Selvaraj would be incomplete without the story of Vandana who has set up a modest stand next to him. Vandana Sanjay Kakkenawar hails from Karnataka and is married with one son who started a job as an architect just recently. So, her hard work is bearing fruit. She comes from 8 am to 10 am every day and brings a menu of upma and poha, sabudana khichdi garnished with sev and coconut chutney, and some delicious looking sheera, mostly recipes, she learnt from her grandmother. Her dishes are all priced at Rs 30 with sabudana khichdi at Rs 40, but the amount is substantial and hygienically served with wooden spoons. She gets up at 5 in the morning and cooks. Her husband helps in the packing and her son hails the rickshaw. She brings only a few items since she must cook herself and sells about a 100 plates till she leaves to devote herself to household chores, something that every woman in India is expected to do, and which ironically does not count as work. Every item is hygienically packed and delivered even to those standing around and eating.

If she gets orders, her ambition is to start a small kitchen with vegetarian food. But she will never forsake this spot, which started her on her road to entrepreneurship. When she first came to stand here in the second wave of COVID, there was not a soul around. Step by step she has built her clientele many of whom are on credit but as yet there is no paper to keep accounts. Just trust.

She is literally a standing example of the spirit of womanhood in our city of Mumbai, of India. If you wish to contact her to place an order, you can call her on 8879749336.

Next time, you pass a street vendor, think of the story of Selvaraj, Vandana and Muthukrishnan, their struggle in a ruthless world, and the imagination and perseverance, with which their jugaad has become part of the backbone of India that is India’s GDP.

Zaikak says, ”The beauty of India is that it is unconscious of its beauty.”

The famous Photographer Margaret Bourke White said watching Mahatma Gandhi walk to his fateful prayer meeting, “There goes a man who has found a way to change the world. But neither he knows it nor does the world.”

Zaikak declares, ”Selvaraj has found the secret of life. But neither he knows it, nor does his wife.”

Selvaraj Anna (80979 77354), Vandana Sanjay Kakkenawar (8879749336),

Muthukrishnan (84895 98020)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)