Aeschylus’s millennia old play gets an epic adaptation through The Suppliant Women

by Yash Saboo November 29 2017, 4:27 pm Estimated Reading Time: 2 mins, 30 secsWritten 2,500 years ago, The Suppliant Women is one of the world’s oldest plays which speaks to us through the ages with startling resonance for our troubled times. In brief, the rudimentary plot of The Suppliant Women is about fifty women who leave everything behind to board a boat in North Africa and flee across the Mediterranean. They are escaping a forced marriage, hoping for protection and assistance, seeking asylum in Greece. Featuring a chorus of local women from London, this is part play, part ritual. Director Ramin Gray unearths an electric connection to the deepest and most mysterious ideas of humanity: who are we, where do we belong - and if all goes wrong - who will take us in? The message is clear, we’re all in this together!

Aeschylus’s play was first performed in about 470 BC and David Greig’s piercing version has already proved how time can change the meaning.

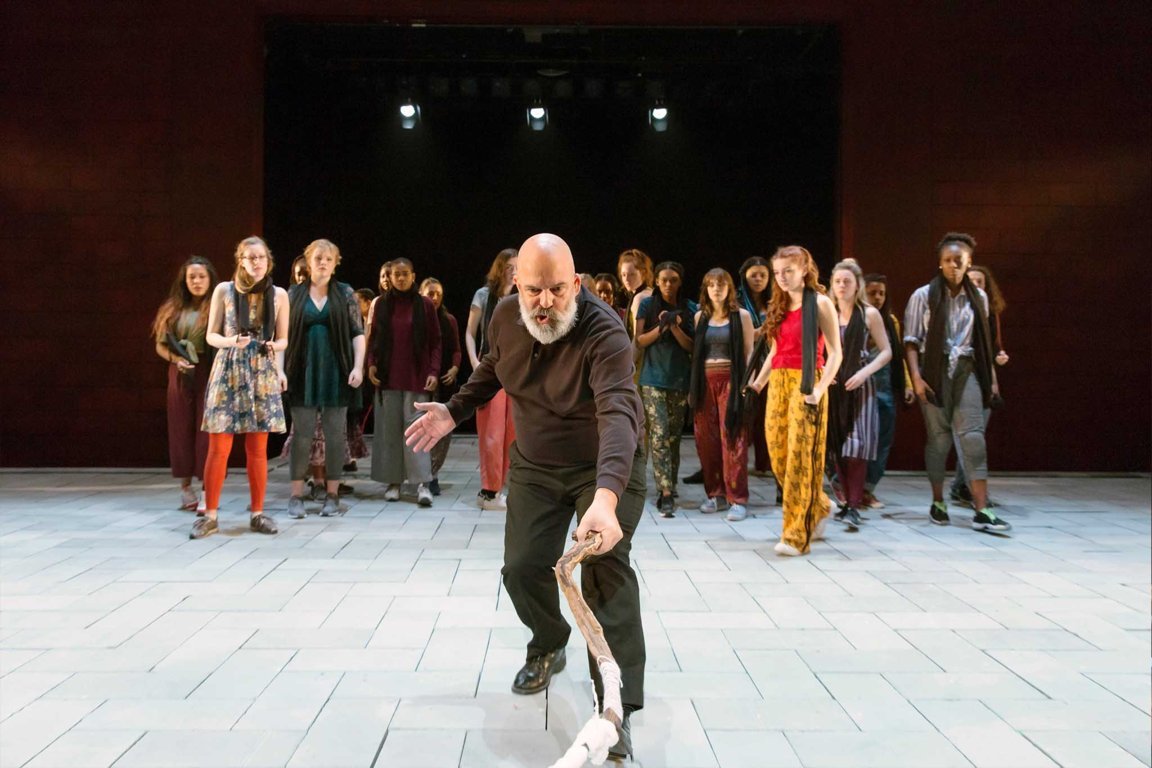

The Suppliant Women begins with the house lights up and a phalanx of young women filling the stage. As per ancient custom, the performance can’t go ahead until respect has been paid to those who have made it possible. A group of women, holding branches bound in white wool, move together across the stage like waves – or a wood bent by the wind. They chant and sing lines which seem – David Greig’s words are the motor of this evening – to move to the beat of a heart. The sound of the aulos, an ancient Greek wind instrument, blows through the air when sometimes the women open their palms, sometimes they advance with clenched fists. Sometimes they are shrouded by black veils, sometimes warmly lit by the candles they hold. They are their own percussive instruments, stamping, and clapping.

Aeschylus’s plot is comparatively simple, yet you feel a real tension about how this issue will be resolved because of the epic performance by the people. It shows Aeschylus to be not only the father of political drama and feminist protest but of music-theatre. It’s also community theatre in the fullest sense making it an unseen adaptation ever before. In a show that deliberately toys with anachronism, there are numerous witty flourishes – the show commences with a libation ceremony – but it’s really almost entirely about the community chorus.

David Greig announced his inaugural season as artistic director of the Royal Lyceum, he said he wanted the theatre to be a “democratic space” where Edinburgh’s population could “gather and encounter each other”. It’s hard to imagine him achieving that aim more consummately than in this first in-house show of the season. And he does it with a 2,500-year-old play. It has a simple message, but one backed up with tremendous power and heart: that it is morally right to take in that fleeing persecution and that is morally wrong to coerce others.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)