-853X543.jpg)

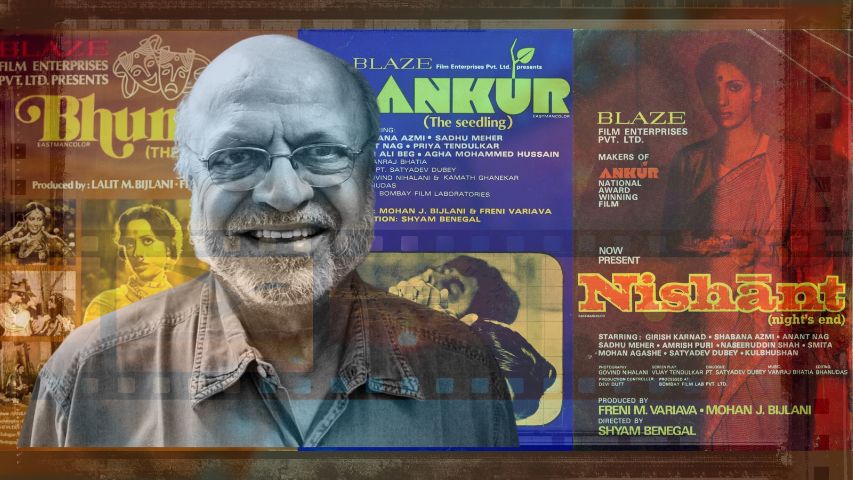

ANKUR: THE SAPLING OF PARALLEL HINDI CINEMA

by O.P. Srivastava October 23 2023, 12:00 am Estimated Reading Time: 6 mins, 33 secs“In the early 1970s, a new class of population was emerging in India, which had started to get rid of the legacy of the past and reboot the country”, writes O.P. Srivastava

Ankur (The Seedlings) was Shyam Benegal’s first feature film, released in 1974. It was also the debut film of Shabana Azmi and Anant Nag. At that time, Bollywood had been churning out typical mainstream masala films like Paap Aur Punya (Shashi Kapoor, Sharmila Tagore), Khote Sikkay (Feroze Khan, Rehana Sultan), Kunwara Baap (Mehmood, Bharthi) and Pran Jaye Par Vachan Na Jaye (Sunil Dutta, Rekha).

Benegal apparently carried the script of Ankur for 13 years before he met Mohan Bijlani (father of Lalit Bijlani) and his partner Freni Variava, who owned a number of theatres. They agreed to invest in this film, an amount of around Rs 5 lakh. Together, the three of them started Blaze Enterprises, a production and distribution company.

Benegal wrote the screenplay for this film, while Satyadev Dubey wrote its dialogue, and Govind Nihalani did the cinematography. While the dialogue of the film is short and crisp, the filmmaker tells the story visually using the flavour of the local sights and sounds.

Ankur won the National Award as Second Best Film in 1975 (The Best Feature Film Award went to Chomana Dudi by BV Karanth). However, Sadhu Meher and Azmi won Best Actor Awards for their acting. The film was also nominated for the Golden Bear Award at the 24th Berlin International Film Festival.

In the early 1970s, a new class of population was emerging in India, which had started to get rid of the legacy of the past and reboot the country. They started getting closer to their roots, and there was a growing consciousness towards rebuilding a socially, economically and culturally independent India.

Ankur demonstrated the consolidation of a production process with realistic aesthetics. In an interview, Benegal stated that he ‘wanted to give the film a sense of temporality by situating its plot in a village in the current Telangana; therefore, the film was shot almost entirely on location in a Telangana village’.

The film is based on a true story that occurred in Hyderabad in the 1950s. Accordingly, the space of Ankur’s narrative is not far from the city of Srikakulam, where the peasant uprisings occurred between 1967 and 1970, following in the footsteps of Naxalbari in Bengal.

Ankur is a layered social commentary. On one hand, it talks about the feudal system, and on the other it tackles the delicate issues of relationships between landlord–servant, father–son, husband–wife and master–mistress.

The film’s most memorable scene is the climax, where Kishtayya (Sadhu Meher) approaches the landlord with jovial innocence and Surya (Anant Nag), bogged down by guilt, beats up Kishtayya mercilessly in frightful retaliation. As the scuffle intensifies, Surya takes out a whip (a symbol of feudal dominance) and unleashes it on Kishtayya. Benegal juxtaposes three elements of feudalism, the landlord, the landless and the land, to end the film with a metaphorical cry of rebellion sowing the seedlings (ankur) of rebellion. The title symbolises the action of a little boy hurling a stone to break a windowpane of the landlord’s house.

This film was a breath of fresh air in the early 70s, largely dominated by commercial films like Bobby, Yaadon Ki Barat, Namak Haraam and Heera Panna. Against this backdrop, Ankur, a so-called art film, ran for 25 weeks in Mumbai’s Metro theatre, which was quite an achievement for a low-budget film. Benegal’s direction in Ankur is simple, direct and naturally imaginative. His storytelling is down-to-earth and realistic. Unlike the glitzy, over-the-top melodramas of the era, Ankur made a social statement in a rather subdued manner, much like its deaf-mute protagonist Kishtayya, played by Meher.

The 125-minute film was considered slow, but still garnered a lot of word-of-mouth attention. Benegal’s cinematic techniques involved letting the camera linger upon the expressions of the actors’ faces long after the point where most directors would say cut. Consider the scene where Lakshmi (Shabana Azmi) stands at the window and watches the funeral procession of a woman pass by the house. The camera gives the audience a glimpse of the goings-on, but mainly focuses on Lakshmi’s face, letting them watch her expressions. The shot takes you inside the character’s mind, and one feels one knows what she is thinking.

Ankur was an independent film with a small budget. Sound played an important role in making it an enjoyable cinematic experience. The sound effects designed by Jayesh Khandelwal resonate with the area’s local sounds (rustling trees, irrigation pumps, bullock carts, local rituals and processions) to blend beautifully with the storyline against a rural backdrop.

Ankur was cinematographer Govind Nihalani’s first film, as it was also Shyam Benegal’s. Talking about Shyam Benegal’s style of filmmaking, Nihalani mentioned that ‘working with Benegal was like being a part of an extended family’. He said, “Shyamji believes in improvisation and discusses the shot in detail with the unit members, and this actually helps in reading the director’s mind. The shot breakdown and the framing are decided on location in consultation with the cinematographer”.

This approach helped Nihalani give the film’s narrative a realistic and gritty feeling. It beautifully captured the mise en scene, the slow-paced life in a hot and arid Deccan village, swaying palm trees, sunsets and sunrises, the dilapidated temples, rituals and flavour of the Hyderabadi/Dakhani zubaan. And, of course, the bumpy rides of vintage cars, which could only be started with the help of low-caste villagers.

Every film tries to use colours to highlight its subtext. This film beautifully used the red and blue colours in local costumes, especially those of Lakshmi, including the stark red of her big bindi.

It is said that Waheeda Rahman was originally approached for the role of Lakshmi, but she declined the film. Benegal took a huge risk in casting Azmi, knowing it would be her debut. Nag also made his debut in this film. As a hearing impaired character, Meher probably played his best in this film. He is absolutely convincing as a hapless, oppressed, low-caste, jobless man, who turns to stealing and drinking to escape the oppressive ways of his fellow villagers. Before he became an actor, Meher was an assistant on Benegal’s documentaries.

In her memoirs, A Patchwork Quilt, Sai Paranjapye writes, ‘Sadhu Meher was a gentle, studious soul from Orissa. He had a very expressive face and a deep understanding of character. Unfortunately, a speech defect from birth hindered him from delivering his dialogues properly. He had a heavy tongue and rather thick lips, so the words faced a speed-breaker, as it were, and were uttered with difficulty. Sadhu got a terrific break. Shyam Benegal cast him opposite Shabana Azmi in his debut film Ankur. The first two days of shooting were frustrating. Sadhu just could not deliver his lines. After many retakes, someone had a brainwave. Why not make him deaf and dumb or speech-impaired to be politically correct? That was done and Sadhu sailed through. Such was the impact of his poignant onscreen portrayal that he bagged the National Award for Best Actor that year”.

Apart from massive critical acclaim, Ankur became a commercial success as well, earning substantial revenue for the producers, who then financed Benegal’s next film. Benegal followed the success of Ankur with a trilogy, Nishant (1975) and Bhumika (1977).

Ankur is an indictment of the unjust and unequal socio-economic system we live in. Without resorting to polemics, Benegal highlighted the inequalities in our society through his films, beginning with Ankur.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)