-853X543.jpg)

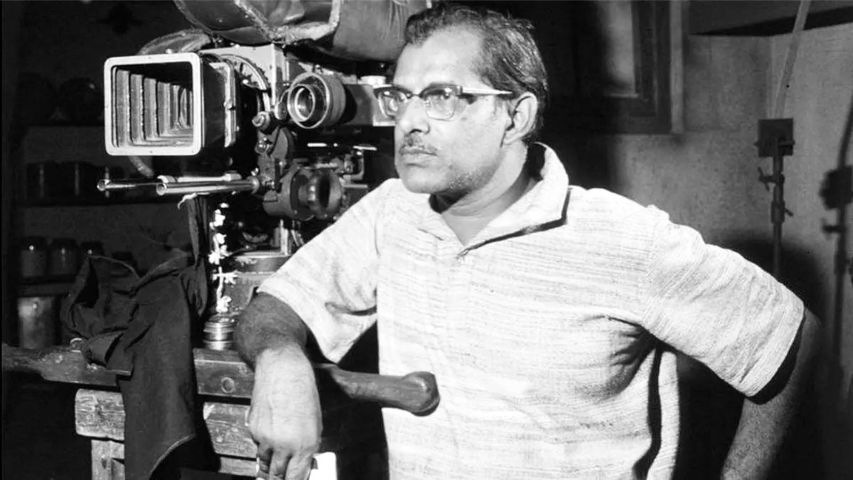

HRISHIKESH MUKHERJEE: THE EVERYMAN FILMMAKER

by Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri August 28 2023, 12:00 am Estimated Reading Time: 32 mins, 21 secsHrishikesh Mukherjee passed away at the age of 83 on 27th August 2006. On his 17th death anniversary Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri analyses and discusses the filmmaker’s work.

A debut that foreshadowed a cinematic style: The document is important in the context of the era, its filmmaker and the opening sequences of the film, which establishes aspects of the director’s signature style. Consider this plot synopsis in the original song booklet of Musafir: ‘A house vacant and to-let: it is brick and mortar and nothing else. And consider the same house tenanted: it is the whole world in in miniature. Here, within its walls the entire drama of human life on earth is enacted in all its shades nuances. One might say that the boundaries of a house bring the life of the family and the individual in definite focus and sharp relief against a maze of similar patterns scattered and diffused all over the world.’

It is 1957. And the filmmaker, making his debut, is Hrishikesh Mukherjee. The film is important for a number of reasons. It is in all likelihood the first anthology-film in Hindi cinema, narrating three different short stories bound by a common factor - a house that is not necessarily a ‘home’. The people who inhabit the house are only passing through, mere travellers who stay for some time and then move away. The stories, bringing together the three aspects of life, birth, marriage and death, were written by Mukherjee himself, in collaboration with a giant of cinema, Ritwik Ghatak, which revealed the director’s Bengal roots that would shine through in some of his finest films.

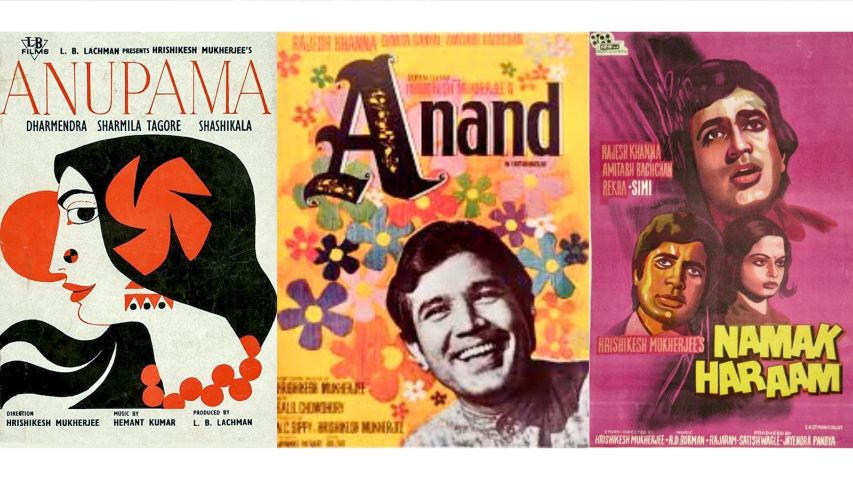

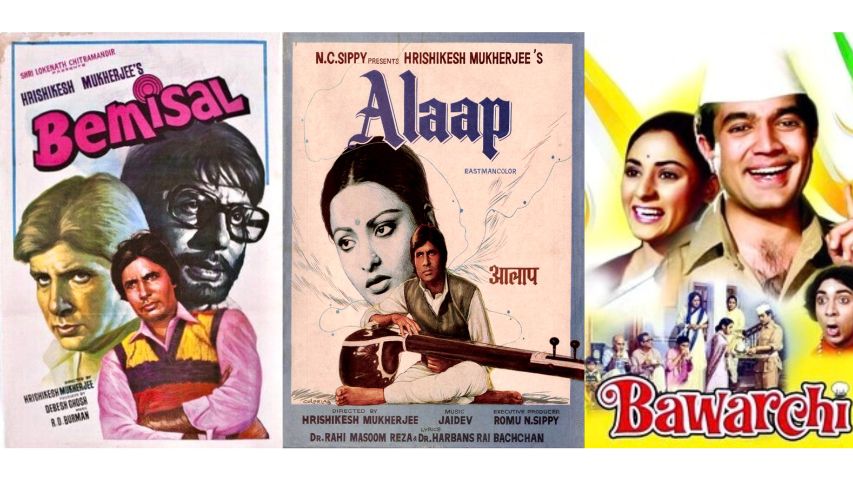

Time and again he would dip into stories originating in Bengal, making them palatable for a pan-Indian audience: Anuradha (a Sachin Bhowmick story that appeared first in Desh magazine), Biwi Aur Makaan (inspired by the Bengali film Joy Maa Kali Boarding), Satyakam (from a novel by Narayan Sanyal), Bawarchi (from the Tapan Sinha classic Golpo Holeo Sotti), Bemisaal (based on a novel by Ashutosh Mukherjee, which was remade from the Uttam Kumar starrer, Ami Shey O Sakha), among others.

And this is the only film that features a song sung by Dilip Kumar (a duet with Lata Mangeshkar), again providing an insight into how this unassuming young man had the courage of conviction to cajole the biggest stars of the era, right through to the 1970s and 80s, to do his bidding. From Dilip Kumar to Rajesh Khanna to Dharmendra to Amitabh Bachchan to Rekha, Jaya Bhaduri and Sharmila Tagore, each went out of his or her way to star in his films at a fraction of their market fees. Of course it goes without saying that each of these actors had their finest roles in films directed by him.

Musafir opens with Balraj Sahni’s voiceover and the camera coming to rest on a house: ‘Lakh lakh makaan aur in-mein rehnewale karodon insaan. In karodon insaan ke sukh dukh, hasne rone ke maun darshak hain yeh maun makaan. Theek musafiron ki tarah yahan log aatein hai, rehte hain aur chale jaatein hain. Yahin janam hota hai, vivah hota hai aur hoti hai mrityu. Musafir teen kirayedaron ke jeevan chakron ki kahani hai jo ek ke baad ek is makaan mein rehne aate hain’ (Scores of people live inside these houses that are mute spectators to the ups and downs of their lives. People come here like travellers and leave. Some are born here. Some get married here. And some die here. Musafir is the story of three such tenants who came to live in this house).

It immediately establishes a theme that one discerns in many of Mukherjee’s ‘serious’ films – the transient nature of life and relationships. Our life is nothing but a winter’s day, or as one of the most beloved characters in one of his most loved films, Anand, says: ‘Babumoshai, zindagi aur maut uparwale ke haath mein hai, jahanpanah. Usse na toh aap badal sakte hain na main. Hum sab toh rangmanch ki kathputhliyan hain jinki dor uparwale ki ungliyon main bandhi hain. Kab, kaun, kaise uthega, yeh koi nahi bata sakta hai.’ (Life and death are in the hands of the one up there. Neither you nor I can change that. We are all puppets on stage whose threads are in his hands).

In the opening moments of the film, two men walk down a street. One of them is the actor David Abraham, who remained an integral part of Mukherjee’s films for over twenty-five years, and who was incidentally cast as a sutradhar or naatak rachita (drama orchestrator) in almost all the films – never quite central to the narrative but operating from the side-lines with his everyday wisdom. It is possible to see David, and later Deven Verma, as standing in for the director himself, orchestrating the mayhem and bringing resolution that ensues in most of his comedies: Chupke Chupke, Gol Maal and Khoobsurat, to name just a few.

In Musafir, David (playing a landlord, Mahadev Chaudhury – interestingly, in a later Mukherjee film, David’s character is named Uncle Moses, in Jai Arjun Singh’s words in his biography, The World of Hrishikesh Mukherjee, ‘doling out commandments and cracking jokes on behalf of a very benevolent deity’) says, ‘Yeh raha mera makaan. Saari duniya mein aisa makaan nahin milega. Haan, iss makaan mein saari duniya mil jaayegi.’ As Jai Arjun Singh further mentions: ‘Houses, as facades, sanctuaries, prisons or settings for self-discovery, are central to Hrishi-da’s work.’ It is not surprising then that some of his most well-known works play out in the confined spaces of a house.

A little later, Mahadev elaborates: ‘Yeh makaan nahin kaamdhenu gaay hai jo khaaye bhi kum, doodh de zyaada – aur upar se gobar muft.’ (This house is like the kaamdhenu, the miracle cow of plenty, it eats little, is generous with its milk. And, as a bonus, you have the dung).

At a monthly rental of Rs 80, the place is a steal, and Mahadev says, ‘Main rupaye ka bhooka nahin hoon’ (I am not hungry for money), almost echoing the director himself, who remained committed to his genteel middle-class bhadralok outlook in most of his films, never going arthouse or highbrow but seldom kowtowing to the demands of the box office. This says something about his filmography, that whenever he made a film with an eye at the box office, Dev Anand-Sadhna in Asli Naqli, Biswajeet-Mala Sinha in Phir Kab Milogi, Rekha in Jhoothi (an unconvincing attempt to rekindle the Khoobsurat magic) or Jhooth Bole Kawwa Kaatey (starring the 1980’s superstars Anil Kapoor and Juhi Chawla), he came a cropper. In fact, he made it fashionable to cast the biggest names of the era. Among them were Dharmendra, Amitabh Bachchan and Rajesh Khanna, but also, later, Shatrughan Sinha (Naram Garam), against type. Not just that, he also gave the vamps of Hindi cinema of the 1960s and ’70s, Bindu, Shashikala and Aruna Irani, some of the most atypical characters in films like Abhimaan and Arjun Pandit (Bindu), Anupama (Shashikala) and Mili and Bemisaal (Aruna Irani).

A little later in the film, another sequence provides yet another insight into Mukherjee’s filmmaking philosophy. A car stops outside the house and the owner asks Mahadev if he knows where house number 35/2 is. Mahadev replies, ‘Yes, I do.’ He walks away, not bothering to show the car owner the way to the house. When asked about it, he says he felt it necessary to answer only what he had been asked. ‘Main faltu baatein nahin karta (I don’t talk more than is necessary),’ he elaborates.

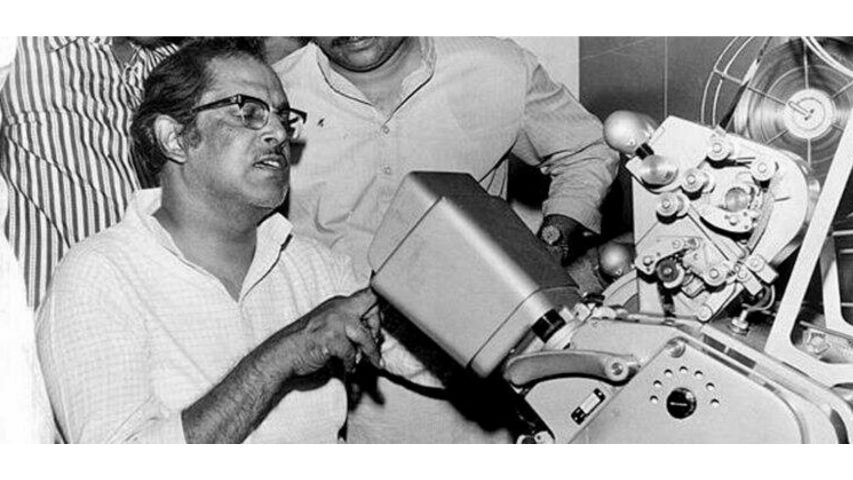

Now, this not only illustrates a signature style of the way his films were written, that throwaway one-liners, but also the economy he brought to his films. Bringing into play his learnings as an editor (he started out as an editor and was one of the finest in the country), and discipline as a mathematician (he had trained as one), he was aware of budgetary constraints. He would not compete with the big budget films of the time and had to be economical in the way he shot his films to make them viable at the box office. At the same time, to keep his unit employed he would often shoot two to three films in a year.

So, time was of the essence. As Gulzar, a frequent collaborator on Hrishi-da films, says, ‘What I took most from him was his efficiency. Hrishi-da was very clear about not taking extra shots or extra angles. He had it all planned in his mind.’ In effect, Hrishikesh Mukherjee edited the film in his mind even as a shot it, economizing on shot-taking.

The origins: It goes without saying that much of what we see as the Hrishikesh Mukherjee style was developed from his days as an editor on films and then his association with Bimal Roy. The Partition in 1947 affected the film industry in Bengal adversely. Like its once-flourishing jute business, after partition, all the jute-growing areas went over to Bangladesh and India was left with jute mills, leading to a tremendous shortage of raw material for the mills, the film industry too suffered a huge loss of viewership. As the industry floundered, before its recovery in the 1950s with the films of Uttam Kumar and Suchitra Sen, and then Satyajit Ray, a number of professionals, working primarily behind the scenes, moved to Bombay.

Leading this migration was the legendary Bimal Roy, who had already established himself as an important filmmaker with Udayaer Pathey. Among the ones who accompanied Roy were assistant director Asit Sen, writer Nabendu Ghosh, dialogue writer Pal Mahendra, actor Nazir Hussain, followed by composers like Salil Chowdhury and Hemanta Kumar, and Hrishikesh Mukherjee - twenty-seven years old at the time, he had been Bimal Roy’s editor at New Theatres. He arrived in Bombay in the first week of February 1950.

Hrishikesh Mukherjee began his career as an editor, in 1945, learning on the job at New Theatres in Calcutta. He said in an interview, ‘There was no FTII (Film and Television Institute of India) then, and we learned mostly through observing others at work or while working ourselves. Those who could have taught us did not. World War II brought a slump in film production, and even those willing to teach could not.’

They made a close-knit group, living in a small house in Malad, dreaming of bringing new stories and a social consciousness to Hindi films, which had in the 1940s fallen prey to fly-by-night operators out to make a quick buck in the war-torn years. The studio system was on its last leg with legendary studios like New Theatres, Bombay Talkies and Prabhat no longer the force they were in the 1930s. And with New Theatres in Calcutta being the alma mater of this group of film enthusiasts, it wasn’t surprising that they brought a strong Bengali sensibility to their work, creating, in the words of Dilip Kumar, ‘a mini-Bengal in Bombay’.

In her introduction to the anthology on her father Bimal Roy, The Man Who Spoke in Pictures, Rinki Roy Bhattacharya quotes Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s account of the formation of Bimal Roy Productions, which would nurture a number of talents (including Gulzar), and make some of India’s finest films for over decade: ‘After watching Kurosawa’s Rashomon at Eros cinema, some of us along with Bimal-da were returning home in a double-decker BEST bus. The film had left a tremendous impact on us. We were all silent…“Why can’t we make films like this?” He was quiet at first but suddenly exclaimed, “Who will write the film?” I promptly offered to write. We decided that all unit members will have a share in the production company. And so Bimal Roy Productions was born in a double-decker BEST bus!”’

Hrishikesh Mukherjee played an important part in the growth of the production company, with his work as editor, assistant director and scenarist on some of its most important films including Parineeta, Madhumati and of course, Do Bigha Zamin, the film that established Bimal Roy as the foremost of Indian film directors and gave India a new cinema, a couple of years before Satyajit Ray took the world by storm with Pather Panchali.

Hrishi-da had already edited Bimal Roy’s films like Pehla Aadmi and Maa (for New Theatres), and it was he who turned Salil Chowdhury’s story about a rickshaw-wallah into the twenty-four-page screenplay that became Do Bigha Zamin (the title itself harks back to Rabindranath Tagore’s poem ‘Dui Bigha Jomi’. Not only that, it was his narration of the screenplay that convinced the urbane and city-bred Balraj Sahni to play the peasant Shambhu.

A few years later, in the wake of his first film, Musafir, Hrishikesh Mukherjee moved into his own house in Carter Road, Anupama, which many people who knew or worked with the filmmaker described as a veritable ‘Bengal Lodge. Actor and star Biswajeet Chatterjee recalled in an interview to Jai Arjun Singh, ‘Even after living so many years in Bombay, he was still a pure Bengali. Everyone who arrived in Bombay from Kolkata would treat his house as Bengal Lodge. Kali Banerjee, Utpal Dutt, and so many others would go straight there from the station.’

Biswajeet, who starred in a couple of the filmmaker’s lesser-known films like Phir Kab Milogi, Pyar Ka Sapna and Do Dil, and the underrated Biwi Aur Makaan, among his best comedies, proudly remembers: ‘Though I have never worked for Hrishi-da in any of his real classics, the only Bengali film Hrishi-da ever directed was my production, Chhotto Jigyasa. I had a problem with the original director, he left, and it seemed like the film wouldn’t be completed. But Hrishi-da came to my rescue without a fuss. He was credited only as chief adviser.’ This was an aspect that is seen notably in the director’s many contributions as an editor.

Casting against type was his forte. Probably the one lasting contribution of Hrishikesh Mukherjee as a filmmaker is the way he cast the biggest stars of Hindi cinema in direct contrast to their box-office image. And he did this in films that owed themselves to his Bengali sensibilities that operated on limited budgets.

The earliest of these is Kishore Kumar in the director’s maiden film, Musafir. In the 1950s, Kishore Kumar was, along with Dilip Kumar, one of the most popular stars. He however was an out-and-out comic star. Possibly taking a leaf out of his mentor Bimal Roy, who cast the singer-star in a serious mode in Naukri, Hrishikesh Mukherjee did the same with Kishore Kumar in Musafir. In fact it is possible to see the Kishore characters in these two films, Ratan and Bhanu, as mirroring each other. Musafir of course remains Bengal superstar Suchitra Sen’s first Hindi outing.

One of the director’s most drastic and dramatic actor choices remains Dharmendra. By the time Hrishikesh Mukherjee first cast the star in his film, Dharmendra had been part of popular Hindi cinema, which normally cast him as in the romantic mold in primarily women-driven films (seven of these with Meena Kumari). He broke through as an action hero, going shirtless, with the 1966 blockbuster Phool Aur Patthar. Over the next couple of decades, he came to be regarded as the ‘He-man’ of Hindi cinema, an action hero like no other. Yet, in the films of Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Dharmendra was probably what one could never imagine: the middle-class Bengali bhadrolok. It was in that very year, 1966, that Hrishi-da, once again probably taking a leaf out of Bimal Roy who cast the actor in a different mold in Bandini, had Dharmendra play a jobless writer and teacher, dressed in the quintessential Bengali dhuti, crooning one of his most atypical songs, ‘Ya dil ki sunoh’, in Anupama.

The pinnacle of their collaboration came in 1969 with Satyakam, considered by many to be Dharmendra’s finest performance. As the principled man who will break but not bend, Dharmendra is a revelation in a film that ranks amongst the director’s best. Later, in 1975, a year more famous for Sholay and Deewaar, and by which time both Amitabh Bachchan and Dharmendra had become larger-than-life vigilantes in mainstream potboilers like Zanjeer and Yaadon Ki Baraat, Hrishikesh Mukherjee cast the two superstars in one of Hindi cinema’s most uproarious comedies, Chupke Chupke. In fact, it says a lot about the filmmaker’s clout that at a time when Amitabh Bachchan was in the stratosphere of success, he willingly agreed to play what was essentially a secondary role in Chupke Chupke. The esteem in which Dharmendra held the filmmaker is also visible in the way he sportingly played himself, ‘Dharmendra, the superstar’, in Guddi (Jaya Bhaduri’s maiden film), one of the few Hindi films that had a ‘star/actor’ actually deconstructing his stardom.

Another star who willing cast off his chocolate-boy romantic image for the director was Rajesh Khanna. By the time Khanna acted in Anand, he was a bona-fide superstar with the epoch-making success of Aradhana behind him. Films like Do Raaste, Sachha Jhutha and Kati Patang had made him a romantic heart-throb of millions. Hrishikesh Mukherjee cast him as the spirited cancer patient, Anand, in the eponymous film, giving him one of his most enduring roles. He also had the star act in what was essentially an ensemble piece, Bawarchi, in a character that had no romantic interest opposite him (in fact, that the film’s main heroine, Jaya Bhaduri, calls him brother, became fodder for gossip magazines!). Hrishikesh Mukherjee was, reportedly, the only filmmaker with whom Rajesh Khanna refrained from throwing tantrums and made it a point to be on sets in time.

However, it is his, for-all-practical-purposes, final collaboration (Naukri in 1978 is too inconsequential a film) with Rajesh Khanna, Namak Haraam, that stands not only as the actor’s finest hour but also as the film that dethroned him from his perch and gave Hindi cinema its biggest superstar, Amitabh Bachchan. And it is with Amitabh Bachchan that Hrishikesh Mukherjee proved how it was possible to cast the star in roles far removed from the ones that defined his stardom.

The Filmmaker behind Amitabh Bachchan’s Angry Young Man: Conventional Hindi film wisdom credits Salim-Javed with the creation of Amitabh Bachchan’s angry young man image, with directors like Prakash Mehra, Yash Chopra and Ramesh Sippy, to name just a few, helming some of the most iconic ‘angry young man’ films. However, even though Zanjeer is credited with birthing the image, and films like Deewaar, Trishul and Shakti popularizing it, the real credit for it should go to Hrishikesh Mukherjee.

More than two years before Zanjeer, Hrishikesh Mukherjee, and his regular team of writers like Gulzar, Bimal Dutta and D.N. Mukherjee, gave us Dr Bhaskar Banerjee or Babumoshai in Anand. And the one thing that makes the film work, apart from the music, is the despair and angst that Amitabh Bachchan imbued Babumoshai with, the first of Bachchan’s angry characters.

Following Zanjeer (which means they were much in production simultaneously with Zanjeer), we have Abhimaan and Namak Haraam, the latter largely instrumental in Bachchan’s superstardom in the wake of Zanjeer. Directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee, both films have Bachchan in roles with bitter overtones. It was a template he would resort to for all his films starring Amitabh Bachchan, barring Chupke Chupke: Mili, Alaap, Jurmana and Bemisaal (probably the finest of Bachchan’s angry man roles). Of course, Mukherjee’s angry young man was vastly different from Salim-Javed’s. For one, he never raised a fist, there were no dishum-dishum, no explosive dialogues and no final catharsis in a fight to the finish. The anger simmered at a subterranean level, as a subtext.

Of these films, Alaap stands out for a number of reasons. And like I have dwelt at length on Musafir as a template for the filmmaker’s career, I would like to consider Alaap as an example of the lengths Hrishikesh Mukherjee was willing to go with Amitabh Bachchan.

For one, in an era when the superstar could not deliver a flop even if he tried to, just look at his roster of films in the years 1976-79, Alaap came a cropper at the box office (the only other Bachchan film of the time that failed miserably was Immaan Dharam, ironically, scripted by Salim-Javed). But while Immaan Dharam was a rank bad film, Alaap has come to be regarded as one of Bachchan’s best, just that it broke away too much from the star’s popular image, with an outlook that is relentlessly bleak.

Second, it cast Amitabh as a trained classical singer, another first (in fact, there are no other films in his career, which had him play a classical singer). For an Amitabh film of the era, it might come as a surprise that the film begins with a dedication to Mukesh and K.L. Saigal and the title credits play out against a visual of Amitabh Bachchan singing the Saraswati Vandana! And though I never bought the argument made by many during the era that his films sounded the death knell for good music, Alaap remains a true outlier among Amitabh’s films, the one with a truly classical score and arguably his finest musical. And though by this time, Kishore Kumar was the recognized and acknowledged voice of the star, Alaap made a change here too with Yesudas providing the playback for the star for the first time, and how!

So, Alaap took one risk too many for a mainstream Hindi film of the era. As the filmmaker himself observed, it was almost blasphemous to have Amitabh play the sitar and harmonium when audiences wanted him to be firing guns. In an interview to Filmfare, he said: “The film had Amitabh Bachchan holding a tanpura, which was too much for the audience to take. Amit’s image of the angry man, always fighting, was becoming very strong then. Besides, the film was depressing, the characters were faced with far too many problems. The classical music base for the songs didn’t go down well either.”

But for the viewer looking for a different take on the angry young man, Alaap, based on a story idea by the irrepressible Harindranath Chattopadhyay, developed by the director, with scintillating dialogues by Rahi Masoom Raza and Biren Tripathy, offers a richly rewarding experience. It begins with Alok (Amitabh Bachchan) returning home after training in classical music. That his father Triloki Prasad (Om Prakash), whom he refers to as ‘Herr Hitler’, does not approve of his passion, is evident at their first meeting when he peremptorily asks Alok what he intends to do with life now that he has had his little diversion in music. He fails to recognize Alok’s dedication to music, and above all, his sense of fair play and justice, setting up a confrontation between father and son that will cast asunder all familial ties.

Though the conflict between father and son is the staple of many a Hindi film, what sets Alaap apart is its approach to the conflict. You can see the understated fire in Alok, in the way he chides Radhiya, his wife, the sister of a humble tongawalla, Ganeshi, for suggesting that he make it up with his father. In the way he dares his father by deciding to make a living as a tongawala. Above all, in the way he reasons that as an artist he would amount to nothing if he cannot stand up to the injustice meted out to his fellow human beings. These are all aspects that feed off his angry man image, but rendered anew, with none of the fire and brimstone of his other films in this avatar. Above all, where Alaap scores is in the way it makes a point about the egalitarian nature of music, one that transcends caste and class. No other Bachchan film has ever done this.

The film is also notable for the way it addresses social and political issues. In one brilliant sequence, more effective for the unobtrusive way in which it plays out, Triloki hails a tonga, realizing that his son is the driver only when he proffers him money for the ride. It says a lot about the way we approach a certain class of people. Triloki does not even look at the face of the rickshawallah till he reaches out to make the payment. Or consider Sulakshana (Farida Jalal), a trader’s daughter with whom Triloki contemplates Alok’s marriage, who tells Alok, ‘Enough is enough, you can’t go on being a tongawalla’ to which Alok’s response reveals our inherent biases against work that involves manual labour. There’s also an offhand comment on the changing face of electoral practices as Triloki Prasad asks his campaign manager to make a bloc-wise breakup of the electorate by caste and religion to ensure that the right canvasser goes to the right region. A practice that has reached its full flowering in many states of contemporary India.

Another beautifully done aspect pertains to the way the film paints the picture of a surrogate family and its strong ties over biological ones. In one of the film’s most telling sequences, as Sarjubai, an erstwhile courtesan who mentors Alok, lies dying, none of the three men around her are related to her by blood. It is a common love for music that has bound them together for a lifetime. That extends to every other relationship that Alok has - with Ganeshi, with his sister-in-law (played with great feeling and charm by Lily Chakraborty), with Sulakshana. In contrast, the one blood relationship, with his father, is fraught with discord and discontent.

What makes this aspect come across so strongly is also Chaya Devi’s performance. Though in many ways, Sarju is the mother figure we see in countless Bachchan films, and though she stands in as a surrogate for his deceased mother, there’s none of the stereotypical melodramatic overtones we normally associate with the mother figure in Hindi films of the era. And that also holds for her portrayal of the courtesan which flies against the conventional portrayal of baijis in Hindi films. It is ultimately the relationship between Alok and Sarju, and between Sarju and the rest that gives the film its narrative strength.

A palpable sense of loss pervades the film, which is as much a lament for a lost way of life, a new more aggressive world replacing a genteel one of adab and tehzeeb and leisure, an era of classical music and its practice coming to an end - the guru at Alok’s music school says, ‘Ab toh sadhana ka lamba raasta hai, jo jeevan ki tarah safal bhi aur kathin bhi hai’. Music calling for a lifetime of commitment and dedication, and thus rendered irrelevant in a world changing by the day. This is also manifest in the way automobiles replace the hand-driven rickshaw, leading Ganeshi to say, ‘Bus mein tel jalta hai, par tange mein janawar ka khoon’ (A bus runs on fuel, but a tonga runs on the animal’s blood).

Alaap epitomizes a lost world in Hindi cinema, when technique and technology had not yet overshadowed content. All Hrishikesh Mukherjee films for that matter are basic when it comes to the technique, he was never breaking new ground with style, but there’s something about the telling that make the films resonate even today. Fans of Amitabh Bachchan may swear by Deewaar and Sholay, Agneepath and Zanjeer, but nothing beats the charming everydayness he imbued his characters with in his films with Hrishikesh Mukherjee.

Right through the 1970s and ’80s, when Bachchan ruled the roost with one commercial blockbuster after another, it is Hrishikesh Mukherjee who brought the actor in Amitabh Bachchan to the fore. Bachchan was also a sport when it came to the director, taking on cameos in films like Gol Maal in a hilarious ‘dream’ song sequence that shows the superstar on his haunches, clutching his head in despair after being ousted as a film star by the new kid on the block (Amol Palekar).

Getting actors to go beyond their comfort zones also extended to actors like Rekha who became a star with Khoobsurat. Or Sharmila Tagore, who has one of her most nuanced roles in Anupama. Or perennial ‘women of disrepute’ in Hindi films like Bindu, Aruna Irani and Shashikala in films already referred to.

The Music: It is one of the ironies of studies on Hindi film music that Hrishikesh Mukherjee is never mentioned in the same breath as others like Raj Kapoor and Dev Anand when it comes music in their films. It is probably because like his films the music in his films too was nuanced, appealing to a demographic that was different from the ones that patronized the Hindi film musical, as also because his filming of song sequences was never ostentatious. Like his films, the songs were minimalist.

However, there is no doubt that his films boast of some of the finest of Hindi cinema. The songs in Anari continue to evoke the innocence of a lost era. Abhimaan of course is arguably the greatest of Hindi film albums, but even before that he had experimented brilliantly with Pandit Ravi Shankar in Anuradha. Unlike filmmakers and actors of the era who had their own camp of composers, Raj Kapoor: Shankar-Jaikishan, Dev Anand: S.D. Burman, Dilip Kumar: Naushad, Hrishikesh Mukherjee experimented, with great success, with a wide variety of people.

Hemanta Kumar’s songs in Anupama are eternal favourites. Vasant Desai scored for Ashirwaad and Guddi. While the former had what is arguably the first rap song ever, ‘Rail Gaadi’ (much before Sugar Hill Gang’s 1979 Rapper’s Delight, or Baba Sehgal’s rap in the 1990s), the latter gave us the quintessential school prayer in ‘Humko mann ki’ and that evergreen ‘Boley re papihara’. Madan Mohan (Bawarchi) was as much a part of his scheme of things as Salil Chowdhury (Anand). R.D. Burman scored evergreen songs for Hrishikesh Mukherjee in films like Buddha Mil Gaya, Phir Kab Milogi, Namak Haraam, Jurmana, Gol Maal, Khoobsurat and Bemisaal.

Among his finest musical films is Alaap, composed by Jaidev, that outstanding and criminally neglected and overlooked composer. I have already mentioned the film’s classical music credentials and this being the Amitabh Bachchan film with the finest music. Rahi Masoom Raza too never scaled the highs as a lyricist that he did with Alaap. But what makes the music really stand out is the way it is integrated with the narrative and underlines its many relationships, with some of its most memorable vignettes woven into the songs.

Consider, Yesudas’s mellifluous ‘Chand akela jaaye sakhi ri’, for example, in which Alok pleads the moon’s case as a plaintiff, with Amitabh’s mock courtroom dialogues punctuating the song. Not only does it provide the narrative with some lively moments, it also establishes the deep bonding between Alok and his sister-in-law, one of the driving forces behind his passion for music.

Then there’s ‘Ayi rut sawan ki’, impeccably rendered by Bhupinder and Kumari Faiyaz, which provides a delectable shorthand to Sarjubai’s relationship with Raja Bahadur. In ‘Nai ri lagan’ (Yesudas, Madhurani and Faiyaz), you have the film’s most heartwarming scene as Alok bends down to touch Sarju’s feet during a Holi celebration, in a typically, for the film, low-key commentary on music’s ability to upend social and caste rigidities.

And the pièce de resistance: Harivansh Rai Bachchan’s ‘Koi gaata, main so jaata’. Both a lullaby and an elegy, I wonder if there’s another song in Hindi cinema that brings these two forms together with as much feeling as this. In three-and-a-half minutes of exquisite poetry, flawless composition and heartfelt rendition (by Yesudas), the song provides a snapshot of the film and the journeys its characters have undertaken.

As Editor: Given his achievements as a director who pioneered a whole new way of making films within the confines of mainstream cinema, his one contribution that we often tend to overlook is as an editor. As already mentioned, he started out as an editor and edited a number of Bimal Roy films before branching out on his own as a filmmaker. Given the constraints of the kind of cinema he made, his acumen as an editor stood him in good stead in economizing on shot-taking.

The iconic climactic scene in Do Bigha Zamin owes a lot to Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s editorial vision. He had originally edited the sequence rather conventionally - the wheel coming off, the camera tracking the wheel till it falls over, then a slow fade-out, followed by Shambhu’s son opening a door and asking why his father had not come home. Dissatisfied with how it was playing out on screen, the young editor recut the scene, making it more chaotic - the final cut has sounds of people shouting and screaming, vehicles coming to a halt, interspersed with a shot, from Shambhu’s perspective, of the Victoria Memorial toppling over. Then a sharp cut to the boy opening the door.

It will be worthwhile to go back to Musafir again to see how his understanding of cutting patterns played out in his own films. Given the nature of circularity and repetitiveness that characterizes life, there is a certain uniformity in some characters and camera angles across the three stories. As Jai Arjun Singh points out: ‘Each story has a scene – composed in exactly the same way, where a restless, unhappy woman gets up at night and walks across to the window, while a man comes and stands behind her, asking her what is wrong…and David’s Mahadev punctuates the stories by turning the “To Let” sign around with his stick.’

He brought his editorial acumen to bear on other classics of Hindi cinema, like Nitin Bose’s Ganga Jumna and Rajinder Singh Bedi’s Dastak. Another Herculean effort is Ramu Kariat’s Malayalam classic Chemmeen. The production had gone out of hand and the director approached Hrishikesh Mukherjee for a salvage job. Watching the footage, Hrishi-da realized that the director had followed T.S. Pillai’s novel too closely, so that it would probably become unrelatable to those who were unaware of the book. In order to make it a more visual narrative, he got Kariat to shoot the sea, both when it was turbulent, waves crashing against the shore, and when it was calm. These shots punctuated the narrative better than conventional dissolves and added what came to be recognized as one of the film’s greatest achievements: ‘the sense of nature as a silent, godlike spectator to human drama’, in the words of Jai Arjun Singh.

There is also, of course, the celebrated salvage job on Manmohan Desai’s Coolie. Interestingly enough, Hrishi-da would often hold the maverick director responsible for turning his favourite star into a mass-market hero, a stuntman, from the quiet and intense Dr Bhaskar of Anand and Shekhar of Mili. However, when Desai approached him with what was for all practical purposes footage that made no sense even in the nonsensical world of a Manmohan Desai film, it was Hrishikesh Mukherjee who structured the film and gave it shape. And then there was the incomprehensible Professor Pyarelal, a film so chaotic that not even Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Scissorhands could salvage it. Yet, the film’s poster carried his name more prominently than that of the director Brij Sadanah.

The Legacy: By the time we come to the 1980s, the audience profile was changing and the demographic that patronized middle-of-the-road cinema, of which Hrishikesh Mukherjee was at the vanguard who brought in his wake filmmakers like Gulzar, Basu Bhattacharjee and Basu Chatterjee, was abandoning the theatre for the comfort of VCRs in their drawing rooms. Though he had a string of successful films at the turn of the decade, including Gol Maal and Khoobsurat, and though his experimentation with the biggest star of the time, Amitabh Bachchan, continued with Jurmana and Bemisaal, the personal, intimate cinema that Hrishikesh Mukherjee epitomized, devoid of all the masala of commercial potboilers as also steering clear of the framework of arthouse cinema, was fast going out of favour. His last films stand testimony to not only that but also his own failure to find a new language for the changing times.

However, his thoughts endured. Filmmakers like Sai Paranjpye picked up the mantle with films like Sparsh, Chashme Baddoor and Katha, among others. In recent times the films of Dibakar Banerjee and Rajkumar Hirani have often had echoes of the world that Hrishikesh Mukherjee created, though of course the new crop of filmmakers were edgier and more accomplished technically, or had the kind of budgets that would probably have financed a few films of the master.

His legacy came rudely into prominence in June 2022 when Mohammed Zubair, co-founder of fact-checking website AltNews, was arrested for a tweet with a hotel sign where its name is shown as Hanuman Hotel instead of Honeymoon Hotel. The perfectly innocuous shot was from one of the master’s relatively lesser-known films, Kissise Na Kehna, which suddenly found a viewership more than when it was first released. The shot is typical of the kind of impish humour making a comment on human foibles that the filmmaker was famous for.

After all, what is Khoobsurat but a comic comment on the Emergency? It is worth speculating what a Hrishikesh Mukherjee film would have made of contemporary India.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)