-853X543.jpg)

MANI KAUL’S ICONOCLASTIC USKI ROTI

by O.P. Srivastava August 21 2023, 12:00 am Estimated Reading Time: 5 mins, 21 secsThis film is a juxtaposition of slow-moving close-ups and wide shots layered with lots of silence and interspersed with a few monotonous dialogues, writes OP Srivastava

Imagine you are inside an art gallery. There are many paintings on the walls: portraits, landscapes and abstract paintings. You look at one, trying to understand it, experience it, then move on to the second and then to the next, slowly trying to assimilate each painting’s message. The journey also tells you something about the artist’s background, technique and thoughts. All the paintings are different, yet together they communicate a single chain of thought.

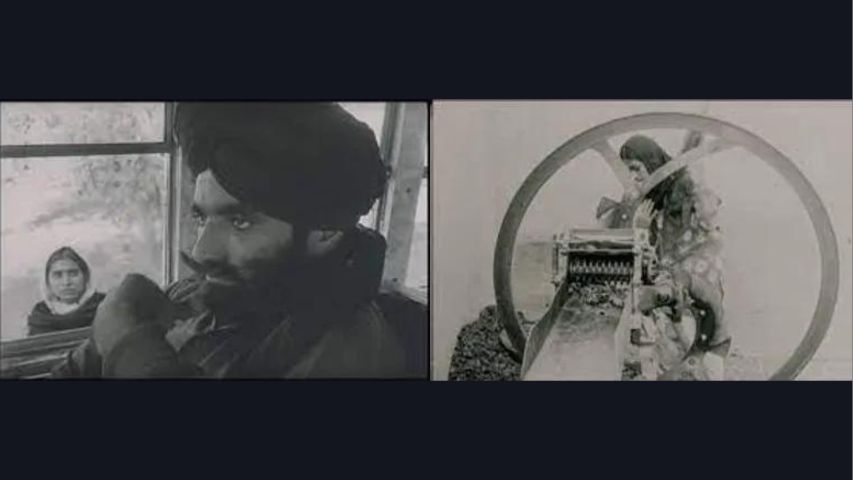

You might have a similar experience when you watch Uski Roti. This film is a juxtaposition of slow-moving close-ups and wide shots layered with lots of silence and interspersed with a few monotonous dialogues. The sequences are rather static and often relentlessly long. The film was shot in black and white, and starred Gurdeep Singh, Garima, Richa Vyas, Lakhanpal and Savita Bajaj. Its cinematography was done by KK Mahajan, and it runs for 110 minutes.

Based on a short story by Mohan Rakesh, Uski Roti (1969) is a film about a young Punjabi woman, Bhalo, who goes to the bus stop every day to give her husband, roadways driver Sucha Singh, his roti. While Bhalo is restricted to a monotonous and laborious routine in the village, waiting for her husband to come home, her husband spends his time drinking, playing cards and with another lady in nearby Nakodar. True to its setting, the film was shot in a village in Punjab.

Uski Roti was perhaps Hindi cinema’s first attempt at breaking away from narrative structure. The cinematic style used in Uski Roti was technically innovative, greatly influenced by the minimalistic style of French avant-garde filmmaker Robert Bresson. The film’s cinematic idiom was also inspired by German poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht’s ‘theory of isolation’ from the ‘epic theatre’ movement. According to this theory, actors would distance themselves from the character inertly, encouraging the audience to think about the larger narrative rather than identify with the character’s emotions. For example, the repeated scenes in Uski Roti that show the protagonist, Bhalo, waiting to serve her husband rotis (daily bread) immerse the character as well as the audience in the stark reality of the situation and not the waiting wife’s emotions.

Regarding the film, the director Mani Kaul said, ‘I wanted to completely destroy any semblance of a realistic development, so that I could construct the film almost in the manner of a painter’.

Like Robert Bresson, Kaul focussed on filming parts of the body, the hands, feet and head, and positioned his actors in front of the camera such that they either faced away from the camera or were in profile, thereby disregarding the convention that the face is the centre of one’s body. KK Mahajan, searching for abstraction in physical correlatives, creatively captured this inactivity in the film. For example, when Bhalo observes a stranger fade away in the dust of the field around her, the shot continues even when the figure has become invisible to the eye. The activity occurs in a differentiated continuum where space is diversified, not restricted to the narrative’s immediate thematic concern.

Kaul explained this process of perceived object and space in films by stating that ‘a tree, for example, will stand for itself in front of the camera and nothing more, unless the filmmaker decides to invest an idea into the tree. Investing an idea into the tree (whether it makes the tree beautiful or ugly) is above all a way of “de-naturing” of the tree…The very tree, which stands for itself will begin to reveal its own meaning when it finds a suitable position in a given set of (standing-for-themselves) images’.

Bhalo’s outer and inner lives are seen through two distinct lenses: a 28 mm wide-angle deep-focus lens, which helps cram more into an image than a longer 50 mm lens, and a 135 mm telescopic lens, which is good for portraiture and ‘bokeh’, the aesthetic quality of the blur produced in the out-of-focus parts of the image.

Kaul’s films held layers of different kinds of poetry. There was lyricism in the way he dwelt upon a tiny grain of time and opened it slowly to hold infinity in his palm, as the English poet John Donne would describe it. He would contrast the tribal and classical to bring epic dimensions to his narrative. Kaul shunned obvious dramatic modes, including frontal humour. However, a scene where a coat is thrown on a peg and keeps falling, or that of a Balkrishna sticker on the glass pane of a bus that keeps looking at you as the road below it moves, making the image levitate, are some of the best examples of purely visual humour that is at once subtle, lyrical and intelligent.

Kaul was enamoured with art, and his deep appreciation for beauty is responsible for the immaculate picture composition in his films. The photography and spacing in Uski Roti were modelled on artist Amrita Shergill’s distinct post-impressionistic depiction of Indian womanhood.

The inability to understand the meaning of the images in Kaul’s films and his style of filmmaking puts off the mainstream audience. By design, Uski Roti obliterates the identification of a theme or meaning in a scene, thereby destroying a ‘structure’ or traditional storyline. The film dared to defy the very form and cinematic traditions of its time, and that is exactly why it stands out.

Born Rabindranath Kaul to a Kashmiri Pandit family in Jodhpur, Kaul graduated from FTII (1966–1967) during Ritwik Ghatak’s term as principal. Kaul himself later became a teacher at FTII. The FFC financed Kaul’s first film, Uski Roti, which was released in 1969 when Kaul was just 27 years of age. John Abraham, the maker of important Malayalam films like Amma Ariyan, started his career by assisting Kaul on this film. Shyam Benegal considers Uski Roti ‘as much a landmark as Pather Panchali’.

Uski Roti won the Filmfare Critics Award for Best Movie. Kaul also won the National Award in 1974 for his film Duvidha and the National Film Award for his documentary film Siddheshwari in 1989.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)