Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan: Genius replayed on a Mega-Monsoon Day in Mumbai

by Khalid Mohamed July 9 2018, 6:43 pm Estimated Reading Time: 7 mins, 14 secsNo reason, no occasion for a replay today except maybe the fact that it’s just another mega-monsoon day. And I’m anxiously searching for music to go with the rhythm of the rain.

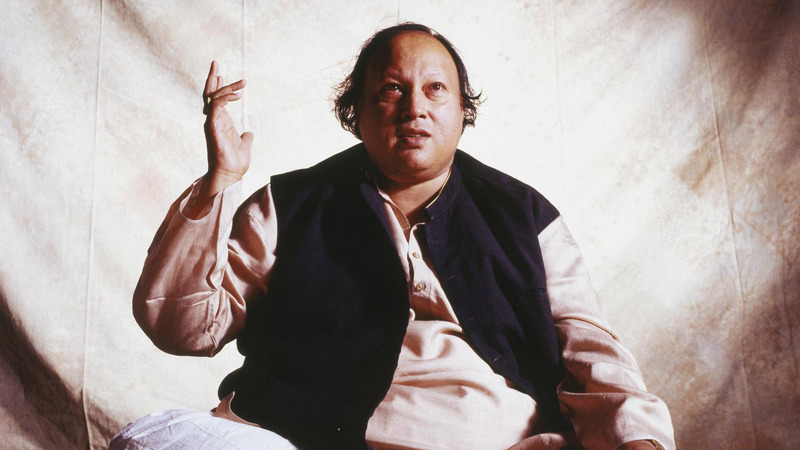

It has to be Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, the ever-dependable to share your feelings with. And to think it will be his 21st death anniversary next month, on August 16 to be precise. The colossal artiste who strikes a timeless appeal.

That’s a voice of limitless artistry – technical as well as spiritual. If you want some one to take you higher, it’s Nusrat bhai who passed away on a day when it was raining in Mumbai. The newspaper obit that had to be rushed (read hacked) in a matter of minutes couldn’t do him justice. But then which obit does?

Clearly, genius can’t be encapsulated in newsprint. Nusrat bhai was one genius I was privileged to know. The other geniuses, in different scales, I’ve had the opportunity to know are M F Husain, R K Laxman, A R Rahman and Santosh Sivan. Two are ageless, the other two are relatively young, Rahman is 51 and Sivan, 54.

Art is ongoing genius. It cannot be a flash in the pan, which Husain, Laxman, Nusrat bhai, Rahman and Sivan have each demonstrated with a sizeable body of admirable work. Okay, so I can already see raised eyebrows… Why Santo?... Is it because he has shot my films? That would be a petty snarl really… You just have to experience how he responds to natural lighting… like the proverbial moth does to a flame.

Perhaps not in my films, but he has this knack of placing the lens at that distinct millimetre where the visual will gain depth and meaning. Of my films, the sequence that Santosh went ballistic with was the Mast mahaul song shot on Sushmita Sen for Fiza. She was being difficult, he told her, “Ma’am I’ll make you look like you’ve never looked before.” And, I think, he did.

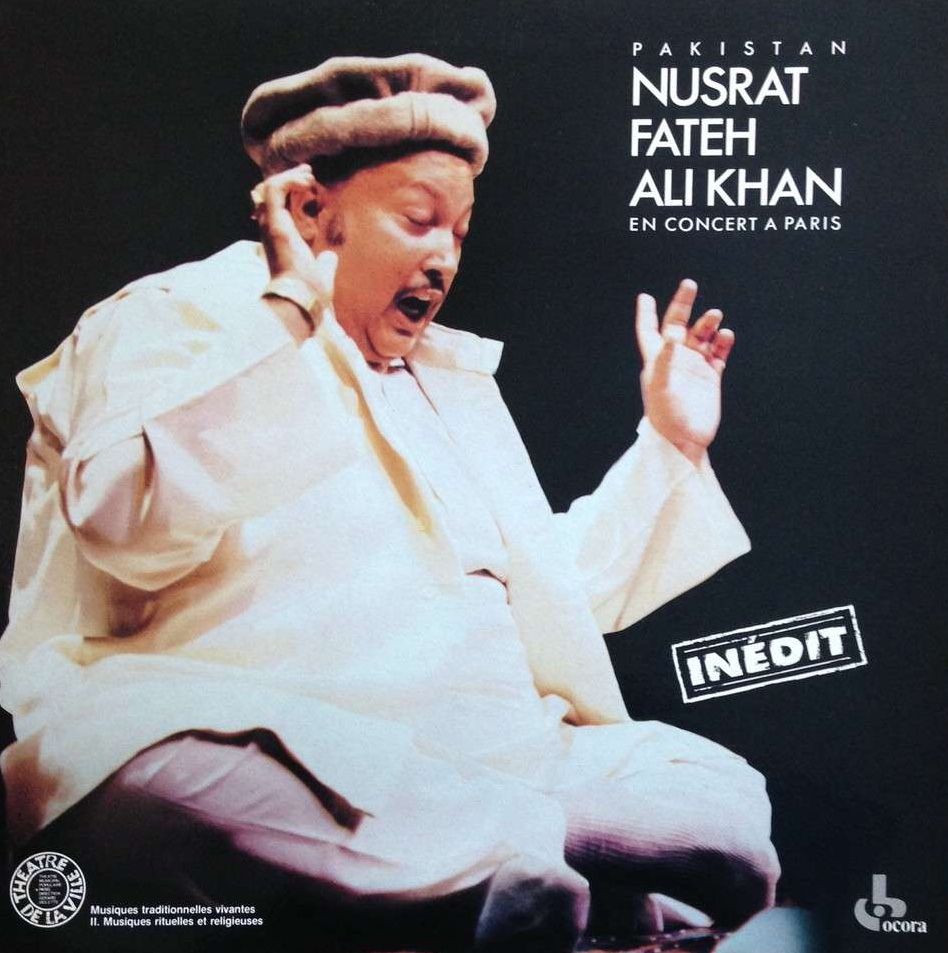

I do ramble. In my defence I can merely argue that the rambling is to the point. For instance, take an album cover of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. His portrait today is photo-shopped; he looks as if he just emerged from an early morning shower, waiting to begin another day, another song. His ‘best of’ compilation has been released by some label or the other, and the covers popped up on the net.

Claims go that he recorded as many as 125 albums. Either you have one, two or dozens of his classic sufi albums (the Real World releases are the best). Then there are his brief, ready-to-radio-air tracks, his lengthy riffs, the qawwalis, the geets, the pop and movie ditties and of course the remixes.

He didn’t approve of the retreads but admitted that his music reached out to a wider, younger listenership as a result. Afreen afreen! Don’t think he was kicked about Lisa Ray walking around, seductively, in the music video though... but kept his reservations off the record.

The one album that’s a staple (read must-possess) is titled Shahen Shah, recorded way back in 1989. Each one of the six cuts here expands on re-listening, with Nusrat bhai’s voice transporting you to another realm. Close your eyes, switch off the lights and listen to Kali kali zulfon ke phande na dalo. It can be variously interpreted as a romantic ode to the beloved or as an invitation to lose yourself in worship, away from the everyday traps and deceits. On the same album, try Meri aankhon ko bakshe hain aansoon, the vocals take you to yet another life-affirming plane.

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s appeal has been to the connoisseur as well as to those who connect right away to snappy beats, hooklines, pithy lyrics and a voice that is distinctive to the point of being inimitable. He was 48 when he passed away, but you couldn’t ever tell whether he was young or old, because he was consistently in his prime.

He was first heard in India via tape-recorded cassettes, much in the manner of the music of Mehdi Hassan preceding the artiste’s visits to and concert performances in India. Allah hoo and Tere bin nahin lagda were played in homes, on tapes and on radios.

Indeed, I hoped against hope that Shyam Benegal would actually get permission to use a Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan track in Mammo, which I had scripted. Benegal loved what he heard of Nusrat bhai, but preferred to use a vignette by a Pakistani female vocalist, which is the director’s prerogative. Just like he replaced the Beatles songs that I’d incorporated in the script – hey, I grew up on the moptops – with Beethoven, saying that he’d grown up on western classical. Fair enough.

One of the perks of being a journalist is that I’ve been in the presence of geniuses, and could be inspired by their thoughts and values. The first time I met Nusrat bhai was at the Juhu Centaur Hotel, courtesy Shekhar Kapur who had used his music in Bandit Queen.

My subject was so shy that I thought I’d return to the office with monosyllables. Gratifyingly, it just took a question on India and Pakistani relations to connect. He opened up, his already swimmy eyes, welled over with emotion. He talked of “music that knows no borders”, and hoped to perform at the Filmfare Awards ceremony that I was once a part of… which well is quite another story.

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan was already the global flavour. Pearl Jam’s Eddie Veber, Oliver Stone, Martin Scorsese used his music. To get him to perform at the show meant a coup. And also a task that would daunt a combo of Hercules-Samson-Rambo. After clearing thousands of yards of red tape, permission was secured at last for Nusrat bhai and his troupe to perform at the show.

My boss at Filmfare, had the knack of achieving the impossible. So there we were on the big evening, Pradeep and I dressed in our black suits and white suits resembling penguins. Very smug, very happy. The show began…

Lucky Ali wouldn’t stop singing, his guitar going on twang-twang-twang… Dharmendra who was being presented the Lifetime Achievement Award was thrilled... we loved him, we were captivated. Then it was the turn of Madhuri Dixit… and it happened. She had to frame freeze.

The cops – and the powers-that-be were then – switched off the power. The closing act of the function couldn’t be performed. Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and his troupe wouldn’t be permitted to sing. That was the first year when a “time limit” was suddenly prescribed for the award show. There had been no precedent.

The man of devotion smiled sadly, his eyes again looking wet. We apologized profusely. He nodded, “It was not your fault, some things are not meant to be.” Fortuitously, my meetings-interviews-chats with Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan continued unaffected. In his hotel suite, he would appear freshly bathed and dressed most often in white or grey.

He liked dressing up, and there was that hint of musk attar. I must have met him every time he returned to the Centaur. His attitude, his voice and his tentative smile remained unaltered. He asked me if I would agree to write a book about his music. “Me? Of course, of course,” I whooped.

He was to return from the U.S. after a spell of medical treatment for his kidney. “Do you know my father never wanted me to sing? He wanted me to become a doctor or an engineer, like all fathers do,” he had said almost inaudibly. It was at the chalisva of his father, a classical musician that Nusrat had first sung as a child. It was at a graveyard; he would narrate, remarking, “That’s why I am not afraid of death. One’s devotion can continue forever.”

I cherish the endless quotes scrawled in an exercise book. I just had a quick look at them, the beats return... Mora piya ghar aaya.. Dum masst masst... so many unforgettables, so many imperishables… his heart goes on in his music.

For me, at least, there can be no monsoon magic, without Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)