Megha Ramaswamy’s documentary, The Last Music Store, entices Khalid Mohamed to stroll down the memory lanes of Rhythm House.

Better late than never. That feeling coursed through me on belatedly chancing upon Megha Ramaswamy’s heart-tugging, 37-minute documentary The Last Music Store, streaming on MUBI channel - on the closure on March 1, 2016, of Mumbai’s Music Paradiso, better known as Rhythm House.

The go-to haunt at Kala Ghoda was dotted with cabin booths, five if I’m not mistaken, for sampling LPs, EPs and singles on turntables, and it wasn’t mandatory to buy one. Couples, age no bar, would canoodle in the quasi-privacy especially during the monsoons, students on a bunk from school and college would spend hours thrilling to the demos of the new LPs of the Beatles (all the records of Elvis Presley and the Rolling Stones weren’t imported perhaps because of music label license fees), and of course there were the serious music scholars, with an armful of classical platters, frowning while they waited for their turn to enter the always house-full cabins.

Senior students, particularly from the nearby Cathedral and John Connon, and Campion Schools, the Elphinstone and St. Xavier’s College crowd, would be shaky because they could be asked to hurry up or quit. Yet they had a savior - a spry, tooth-brush mustache, grey safari-suit wearing salesman, known only by his first name Akbar, who would assure the young bunch, not to worry, and repeat the store’s motto, “Browsing Allowed at Leisure”.

The pride of Kala Ghoda, it is chronicled; the store was founded by Suleman Nensey in 1948, to sell music equipment. The business was on a down curve. Mammoo Curmally joined hands as partner and resolved to market vinyl records instead.

By the mid-1970s, Mammoo Curmally invited his brother Amir, a senior manager at the Imperial Tobacco Company in Calcutta, who quit and came to Bombay to help run the business. Subsequently Amir’s son Mehmood, a jazz aficionado was at the Rhythm House, too. Indeed Amir and Mehmood Curmally and their benevolent lieutenant Akbar, became the faces of the store for the us-still-in-college generation.

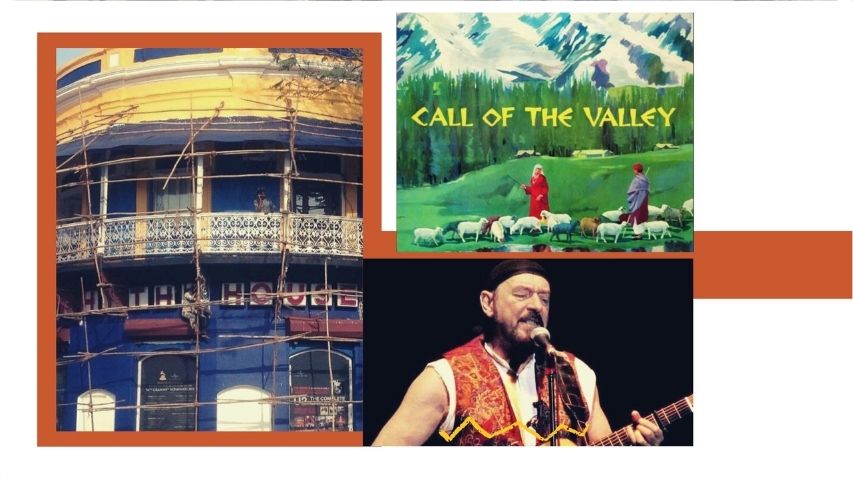

Here were men who were celebrities in their own right. Jethro Tull performed at the store for them. Ravi Shankar, Shammi Kapoor, Nargis Dutt, Zakir Hussain, Asha Bhosle and music composers O.P. Nayyar, S.D. Burman and Shankar-Jaikishen were regular visitors.

The compact, conveniently outfitted, music parlor did have an element of competition from shops on D.N. Road, Colaba, Marine Lines, Dadar and Bandra. No contest though. The others were focused on sales; Rhythm House reverberated with the pure joy of music, behind the sales counter boards posting the month’s bestsellers from the Bollywood and the international repertoire.

Ramaswamy’s documentary, which comprises largely of talking heads, reminiscing about the closure, takes in the loyal staff, the Curmallys and a music expert from a recording label. Therein lies its strength, since their interviews are on the brink of an emotional collapse. Without exception, the employees are faced with the dilemma of locating a job, which wouldn’t be anywhere close to the security of reaching the store punctually, partaking of the pleasure of selling music and returning clockwork the next morning.

On camera, most of them sit before the racks of compact discs and videocassettes, which were offered before the shutdown at absurdly low discount rates of 70 per cent. A middle-aged woman, who would sell tickets from a small table for stage plays for decades, tears up that it’s the end of the road for her now.

The backroom offices of the Curmallys haven’t seen a lick of paint in years. The steel almirahs belong to another age. The once-buzzing and spiffy store wasn’t in a complete shambles though, it could have been rescued, but by whom is the question? Although Rhythm House was as much of the city’s heritage property, since it was a ‘shop’ perhaps, neither the state government nor the patrons of the arts lifted a finger to prevent its end. A subsidy or a donation drive could have helped but then that would have been like asking for the moon.

I am sure anyone who has seen or should see Ramaswamy’s documentary, which was commissioned by Aliya Curmally without giving any brief about its script, will have a personal story to narrate about the store. Mine is that I had once dropped by with a video crew for a short film. A scene was to show a woman selecting a CD or two from the racks. I expected much fuss-‘n-fret from the owners and staff or at least being asked for a wad of money for the shoot. But I just had to ask, and was told, “Go right ahead. No problem. You’ve been an old customer here.” Moreover, the staff helped out in lugging the camera and batteries. From an intercom Mehmood Curmally, tall as a basketball player, in a baritone voice inquired, “Hope all’s going well. Do you guys need any tea or coffee? Water?”

Around then, MP3s, digital downloads, legal or illegal, had made the fountainhead of Indian and global music redundant. Indeed, whenever I would still pick up some CDs, all’d heckle me and say, “You must be crazy. Everything’s accessible on the net. Why pay for something you can get for free?”

In a way, it was like the advent of the Kindle. Why buy books when they can be downloaded or clicked on that thingamajig? If I countered that the scent of paper, the cover design and the print fonts are the way books should be read, I’d be met with raised eyebrows by the millennial, “Uncle, you’ve lost it.”

In the course of one such browsing spree there, I’d asked Amir Curmally, “How’re you coping up with the attack of technology? Will you have to close down?” To that, he had shrugged stoically, “You tell me. Do you have any bright ideas about how I can run this establishment with decreasing footfalls? Still, let’s see. We’ll cross the bridge when we come to it.”

Apparently, a time came for that crossing. Prime real estate prices at Kala Ghoda, and particularly of its artery Rampart Row, was and still are at such a premium that a sale was inescapable. The South Mumbai precinct is now home to a concatenation of tony restaurants, designer wear boutiques, mini-malls and upscale art galleries, standing cheek by jowl to the stray survivor like the Jehangir Art Gallery, which isn’t exactly as inviting as it used to be. On and off, the neighboring Max Mueller Bhavan holds important exhibitions of photographs and art but that’s it.

The quaint and affordable Wayside Inn is dead. Ditto the Samovar in a corridor of the Jehangir Art Gallery. Their absence has spawned pricey specialty cuisine franchises instead. Today, Masaba Gupta sells her haute couture at Kala Ghoda. So does Sabyasachi Mukherjee. The Chemould Art Gallery has shifted. And pavement artists sketching portraits of tourists are an almost extinct species.

Of course, I’m aware that to romanticize the oasis that was, is an exercise in futility. With financial pressures, yesterday’s halcyon halts had to vanish with the wind. The cozy booths to test out vinyl LPs, an USP at the Rhythm House, in fact, had to give way, towards its end years, to stalls of glossy magazines, cellphone appliances, and assorted stationery. To prevent shoplifting, extra staff (wearing red alert uniforms) added to the overheads.

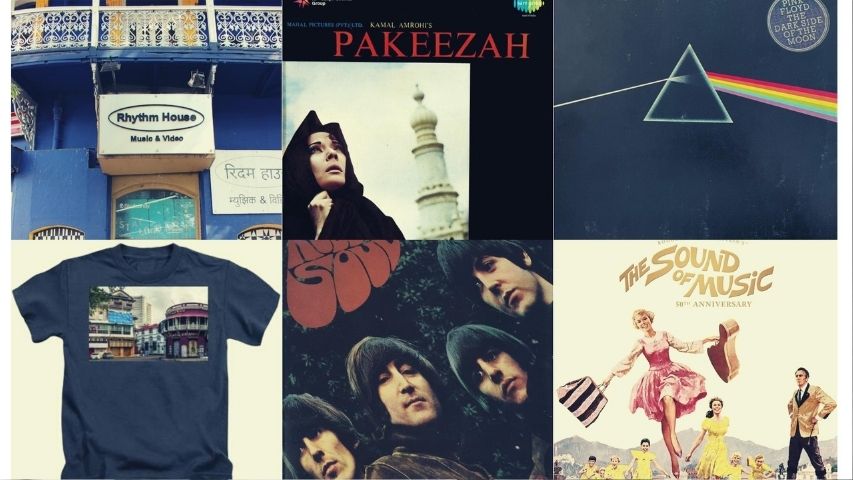

As a school kid, if I wanted to buy the soundtrack of the movie Ben-Hur, of all things, Akbar had cautioned, “Are you sure? It’s not easy listening for kids.” I bought it anyway, the LP is with me, and it’s still not easy to listen to. And if the movie soundtracks of The Sound of Music, Pakeezah, Sholay, plus the Beatles’ Rubber Soul and Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon were sold out, he’d inform me as soon as the fresh stock had arrived. Incidentally, the highest selling album during the late 1960s well into the 1970s was the light classical instrumental Call of the Valley by Harisprasad Chaurasia, Brij Bhushan Kabra and Shivkumar Sharma.

Akbar bhai’s son is an income-tax officer. On connecting on Facebook, he said, “Yes, for dad Rhythm House was his first home. Thousands of music aficionados remember him fondly. We must meet.” We haven’t but Akbar bhai remains the closest I’ve ever got to a music teacher in my life.

The aftermath has been quixotic. In 2017, Nirav Modi, now on the run from the law, had reportedly bought the Rhythm House building through his company, Firestar Diamonds, from the Curmallys. Soon Modi’s high-end jeweler showroom popped up there. Next year, when Modi with his family fled the country, the building was attached and confiscated after legal proceedings by the Enforcement Directorate. Sensibly, industrialist Anand Mahindra had suggested crowd funding to revive Rhythm House, and had met the ED officials to discuss the auction process.

Bombay Municipal Corporation’s Heritage Committee had held a discussion to acquire the place for public purposes, including music promotions. No go. The structure was taken over by Kunal Rawal’s fashion label in 2019. Opened on the first floor of the building, the designer has memories attached to the store. He has stated that his aim was to connect with the heritage property since his label is “an amalgamation of heritage, luxury and the industrial.”

Be that as it may, for right now, the Rhythm House story rests there. Pulling out the plug couldn’t have been easy for the store’s proud, tradition-bound Curmallys.

So here’s, replaying the George Harrison song for Rhythm House: All things must pass/None of life’s strings can last/So I must be on my way/And face another day…

-853X543.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)