-853X543.jpg)

The Filmmaker And The Feminist

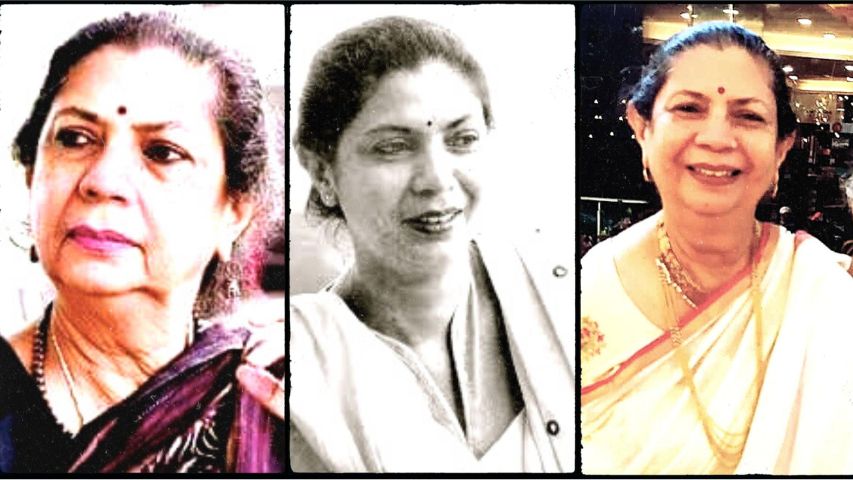

by Vinta Nanda June 20 2022, 12:00 am Estimated Reading Time: 9 mins, 12 secsVinta Nanda chats with Rinki Roy Bhattacharya, one of the first feminists, a woman greatly respected by the entire fraternity fighting for women’s rights in India.

Her mission started when there was more resistance to the idea of women’s liberation than can be imagined. She’s a writer, columnist and documentary filmmaker. She was the vice-chairperson of the Children’s Film Society of India (CFSI) and the founder chairperson of the Bimal Roy Memorial & Film Society. As a freelance journalist, she’s written extensively on films, theatre and art, and feminist issues for publications of The Times Group, The Telegraph, The Hindu and The Indian Express.

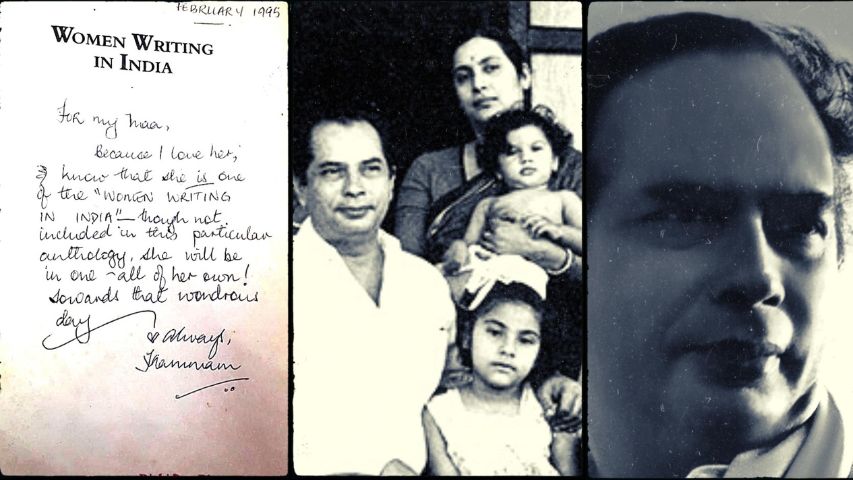

Daughter of film director Bimal Roy, she was married to filmmaker Basu Bhattacharya. Her childhood was spent around prominent writers, poets and artists, who frequented their home noted for gourmet Bengali cuisine.

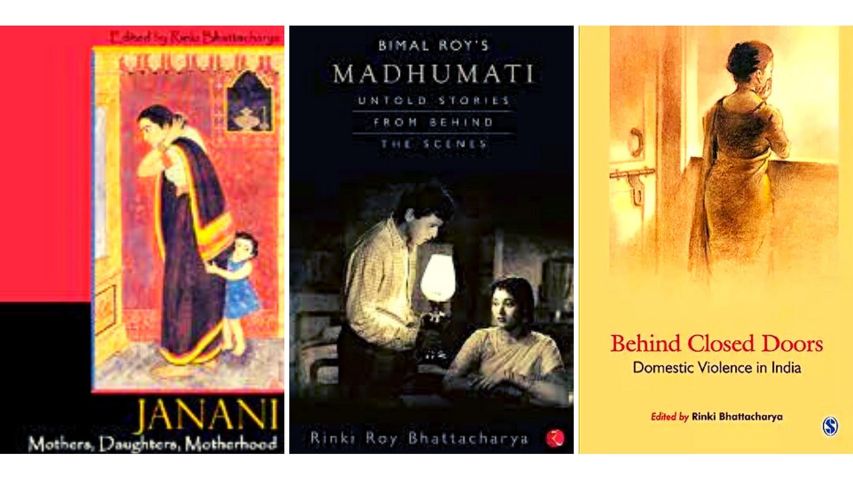

She made her debut in making documentary films with Char Divari, which deals with domestic violence. A sequel followed soon after on related issues involving violence against women in India. She became deeply involved in the Women’s Movement in India and has written several books including Behind Closed Doors: Domestic Violence In India. Bimal Roy - A Man of Silence, Indelible Imprints, and an essay in Uncertain Liaisons are more of her writings. She also published a book on the making of the film Madhumati (1958) by the title ‘Bimal Roy's Madhumati: Untold Stories from Behind the Scenes’.

And I am privileged to know her as a friend. Besides writing for The Daily Eye ever so often, Rinki and I catch up often to exchange notes on films, feminism and food.

I first met her when I was curating the film section of the Kala Ghoda Arts Festival in 2009 for which we had scheduled back-to-back screenings of three films made on Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Devdas – by filmmakers Bimal Roy, Sanjay Leela Bansali and Anurag Kashyap. We hosted a panel discussion at the end of the day, which Rinki gladly agreed to participate in and she had a packed auditorium captivated with her talk.

She’s a storyteller par excellence. I recall the time when she once asked me to accompany her to the National Films Archives in Pune, where she was meeting the director to discuss the digitization of her father Bimal Roy’s films. All the way to Pune and back, she told me stories, three on the way up and three on the way back. And I still don’t know how the roughly eight hours that we spent together that day had passed.

It’s at the time of the release of the book The Oldest Love Story: A Motherhood Anthology (Om Books International) by Maithili Rao and her, edited by Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri, that I got talking to her. Over to her then…

Where did writing start for you and do give us a few nuggets from the beginning of your career?

I began writing out of dire economic necessity from the age of 24 to run our household and to survive. Fortunately for me, I had numerous well-wishers and guardians, for example, there was this iconic film editor of the renowned Amrita Bazar Patrika, popularly known as NKG, short for N.K.Ghosh.

The Patrika incidentally, was India’s oldest print media. Greatly respected too. NKG had attended my parent’s wedding and took me under his wing. I was given a weekly column to write. I would pour into it all the week’s filmy gossip and nuggets. I earned 200 rupees for it, which in those days was enough to run a home. Basu had no income. Mine was welcome.

I am equally privileged to have found similar encouragement from the renowned Hindi writers Dr.Bharati, Kamaleshwar and others. They gave me special features to write for the Times of India group. I was in great demand to write stories for all these important media. I held columns in Times, Economic Times, Mid-Day… not bad, right?

The most triumphant moment as a journalist was to ban the horrendous, vulgar film produced by I.S.Johar called ‘Joi Bangladesh’. This film humiliated the sentiments of an entirely new nation, Bangladesh, with its pseudo sympathy and sentiments. It had six rape scenes shot with the intention to titillate the audience. My Dhaka friends watched it in horror and complained to me. I wrote a strong letter in their underground paper called The People. A cutting of my letter was sent to the then minister of Information and Broadcasting, Nandini Satpathy. She ordered an immediate ban. So 70 prints of the film were withdrawn and never saw the light of day again. Naturally, I was jubilant! There are other stories too but let me not be vain… this ought to be enough?

You, as I know, are among the first few feminists in India. How would you describe the discourse on gender from where you started addressing issues to where it is now?

Vinta, I did not claim to be a feminist to begin with. It just happened that as my principal concern are women’s issues and their rights, their aspirations that are daily repressed by patriarchy, people began to view me as a “feminist” as a result. Women’s rights are greatly endangered because Patriarchy is the dominant culture, in every sphere of our socio-political life. In fact, it is far worse now. Even women make the mistake, the fatal mistake of thinking we have won the gender war. No. We are still marginalized. This is a global concern.

Tell us about the many books you've authored and where the desire to document your father's work came from?

I am a nonfiction writer. A protest writer, if you want to add a label. My writings have emerged from my personal experiences. Take the book on Domestic Violence. The sagas are of women I knew, who I helped rebuild their lives. It was the same with Janani for which I compelled women, mainly noted authors, to revisit motherhood and to break down the prevalent stereotypes. Both books are, to my good luck, well accepted. They are in the Women’s studies courses, which is fulfilling.

As for my father, I was forced to write about my renowned father, Bimal Roy, when I realized to my disbelief that no one had given him that respect he justly and very richly deserves. No one had written a book on my father, which struck me as rather odd considering his huge status, and the enduring popularity of his films. My father is a pioneer who inspired the next generations of filmmakers, yet there was an empty niche. I felt I had to plug it. Bring him back into the limelight. I do this on many levels. In the final analysis, my father’s works are the cinema of protest. Each one of them gently speaks against the injustice that exists in society - whether they are gender, class, caste, or religion.

In retrospect, how do you view your husband's films? How involved were you with his work before you went your separate ways?

Basu was a singularly talented man coming from the backwaters of Bengal. Born in an extremely orthodox Brahmin family, he had a sophisticated sense of cinema, which is rare and quite extraordinary. His films are thus quite unique, especially the marriage trilogy. They have their own space and need not be a part of the parallel cinema.

And yes, I did work behind the scenes for Basu. Was his unpaid secretary!!! Seriously, Basu was not noted for honest dealings with money. Remember, Sai Paranjpye and her cast openly went to town about him after Sparsh? I encouraged Sai to make Sparsh. In fact, I encouraged Basu too about this film. It is Sai’s best work.

I also gave the titles for Anubhav and Aavishkar. I helped with the promotions of both the films, designed sets, costumes - I can go on and on. I worked along with Basu until Grihapravesh. After that I parted company.

Tell a little about him, how the two of you met and got married?

What do you want to know about us, Vinta? It was a love story that soured...

All your children are in creative fields and Anwesha is an writer as well deeply committed to gender. Tell about each one of them in as much detail as you can and about the bonds you share with them.

Each of my children is gifted in their own special way. Aditya had inherited his grandparents’ genes for still photography. He has a portfolio bulging with the most elegant portraits, which is crying to be seen!!! Debonair published his photos and he was paid higher than me at the time! He is a bit actor, well spoken, a filmmaker and potential writer, but he is too lazy.

Chimoo, my older daughter, is exceptionally good at creating events and thriving in the Middle East. Anwesha is a self-elected academic. She has written in my books as well and can do much more. Family life in faraway England comes in the way. She tries to come out. But I have to add my son-in-law to the list of my children, Sagar Arya. He is an actor of repute. He is currently acting in London’s National Theatre to great glory. His portrayal as Veer Savarkar in the play The Father and the Assasin has got rave notices. I am very proud of them all. We have our fallouts, of course, who doesn’t? We have our fun and get on as well as one enjoys.

How did The Oldest Love Story happen? Do share some things about the process.

Maithili has talked about this in the marathon interview you had published earlier. But to give you a brief idea, the book is inspired largely by my earlier collections Janani, Mothers, Daughters and Motherhood, published by Sage in the year 2006.

It was a spontaneous decision to write a sequel. I have to say that the book has been very well received. People are enjoying the essays, we have glowing reviews - what can be better? I am enjoying a great high.

Your long friendship with Maithili - do tell us about her as well.

Maithili and I are very good friends. We support and complement each other. I couldn’t have curated The Oldest Love Story on my own. She has been a rock.

What's next? What are the things you're looking forward to?

You know I am a compulsive writer, Vinta. The other day, I said to someone that writers never age, that they get better. I believe in this too, I will write until my last breath.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)