-853X543.jpg)

Hiralal: A rare biopic on a pioneer of Indian cinema

by Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri March 22 2021, 12:00 am Estimated Reading Time: 9 mins, 6 secsThe fascinating life of Hiralal Sen probably needed more visual flair, writes Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri

However, despite its staginess, there is no denying that Hiralal is an important biopic. As a nation that is mad about cinema, it is surprising how little there is by way of visual documentation of the pioneers who shaped the art form in India. Off the top of my head, I cannot think of any feature film that documents the stories of people like Dadasaheb Phalke (barring the delightful Harishchandrachi Factory in Marathi), J.F. Madan, Fearless Nadia (Riyad Vinci Wadia’s documentary Fearless: The Hunterwali Story is an honorable exception), Baburao Painter and a host of others.

Then again, we rarely get our biopics right. Consider some of the major ones in the last decade or so. Be it our freedom fighters (what a hash we made of Bhagat Singh with three biopics in the same year), or contemporary political figures (The Accidental Prime Minister) or sports (the hagiographical embarrassment that M.S. Dhoni: The Untold Story is, or films like Mary Kom and Bhaag Milkha Bhaag), our biopics seldom ring true. And the problem lies not only with the way they play fast and loose with facts. As Roger Ebert said vis-à-vis the manipulation of facts in Michael Mann’s The Insider - ‘My notion has always been that movies are not the first place you look for facts, anyway. You attend a movie for psychological truth, for emotion, for the heart of a story and not its footnotes.’ The malaise runs deeper.

Seen in the light of the above, there is no doubt about the importance of a film like Hiralal. And cinematic liberties and fictional takes, of which there are quite a few, are the least of its problems. It chronicles an era of Indian cinema that has rarely been brought to screen, if at all, and does so in great, often painstaking, detail. It provides an up-close and personal look at the life and time of a founding father of Indian cinema, Hiralal Sen, whose contribution has been largely overlooked.

Here is a man who predated the films of Dadasaheb Phalke by almost a decade. He is credited with creating what is, arguably, India’s first political documentary - Surendranath Banerjee’s rally to protest the 1905 partition of Bengal - and the first commercial - an ad film for Jabakusum hair oil. But for his own want of business acumen, a certain lack of awareness about the pioneering nature of his work (though the director is at pains to convey his arrogance – ‘there is only one Hiralal’), and a fire on 24 October 1917 that destroyed all his works, it is moot whether he would have been regarded as the creator of India’s first feature film, Alibaba and the Forty Thieves, which he directed but never screened as he fell out with his friend and producer - and thus as the Father of Indian Cinema, instead of Phalke.

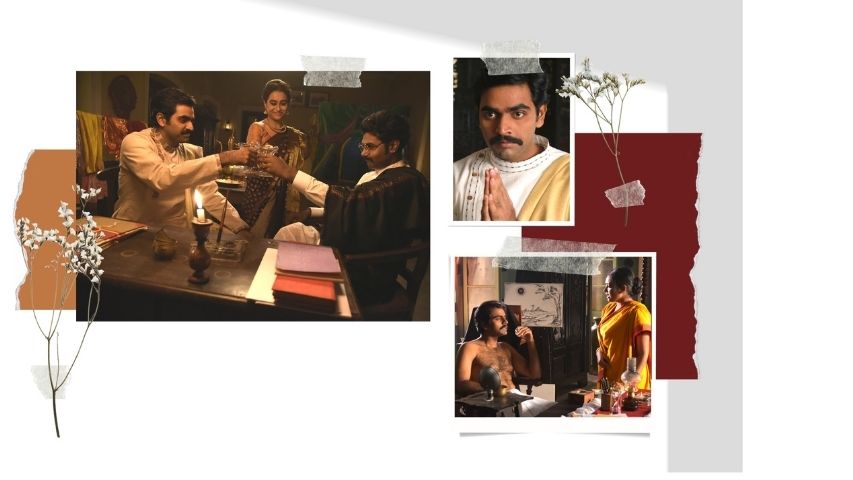

Arun Roy’s film records these events faithfully and provides us with quite a portrait of the era and the dramatis personae. There’s a wonderful attention to detail here – a Bourne and Shepherd exhibition, tent-house picture shows (Stephenson’s Bioscope), the MG cars, the unwieldy hand-cranked cameras and their tripods being lugged around. The lighting and ambience (a hat-tip to cinematographer Gopi Bhagat and colorist Debojyoti Ghosh) are almost picture-perfect. And what a glittering array of characters - from J.F. Madan to Amarendranath Dutta and Kusum Kumari (the stars of Classic Theatre) and that doyen of playwrights Girish Ghosh (impeccably played by Kharaj Mukherjee with a winning combination of arrogance and a sense of time passing him by). And what characters, with egos as big as their contributions to the art form - ‘Ramakrishna called me Kaal Bhairava, the image of Shiva,’ thunders Girish Ghosh at Dutta in the run-up to their parting ways.

It is quite obviously a labor of love for the filmmaker, who says: ‘It took almost two to three years for me, Rudraroop Mukherjee (my researcher), and Sounava Basu (the dialogue writer) to collect all the information and write the script. Budget was a huge issue, especially for an independent director like me. And it became more difficult when I decided to cast new faces for the lead characters.’ The film reportedly was made on a budget of Rs 90 lakh.

However, despite all this, despite the filmmaker’s palpable reverence for the subject, Hiralal never quite soars cinematically. There’s a staginess that informs almost every frame of the film, so that large passages of it look like a play. One example will suffice. Hiralal’s coverage of Surendranath Banerjee’s rally to protest Curzon’s plan to partition Bengal is now stuff of film folklore. Film historian and former professor of film studies of Jadavpur University, Sanjoy Mukhopadhyay has said, ‘In 1904 he captured on film a public rally opposing Lord Curzon’s plan to divide Bengal. To record the immensity of the rally, he placed the camera on top of the treasury building so that he could film the speakers including Surendranath Banerjee against the backdrop of a huge crowd that extended almost two miles.’

Now, that says a lot about the way Hiralal thought of camera placement to get a good angle, that too in what is still a nascent stage for cinema. But in the film we see Hiralal coming across the rally while he is on his way to shoot for Amarendranath Dutta, at which point the director cuts, and has the rest of it as Hiralal’s after-the-fact narration to Dutta. For a film that hails the advent of a new art form celebrating the moving image, the lack of the same for what is perhaps the crowning moment of Hiralal’s work is galling. There is an abdication of that golden compositional principle ‘show, don’t tell’, that dilutes the film’s overall impact and takes away from its merits, of which there are quite a few.

_(19).jpg)

Kinjal Nanda’s performance as Hiralal is of course what powers the film. He plays Hiralal, warts and all, with a rare understanding of the character. There’s interiority about his portrayal that the film could have done with. And he gives it his all in making the transformation from the well-built young man following his dream to the broken, cancer-stricken fifty-year-old who dies in penury. As the rather self-effacing actor tells me over a conversation, ‘I was working in a play when Sounavo, the film’s casting director and dialogue writer, asked me if I would like to try my hand at the film. Arun-da offered me the film after he watched my performance in the play, Code Red.’ What about his preparations for the character? He is reported to have shed over twenty-five kg for the film’s last act and went without water for the last seven days of the shoot. ‘I asked Arun-da for books and research materials on Hiralal Sen, but he waved me away, telling me to make notes around the character from my reading of the script, which I did. I had over twenty-five points for him. Just before the film was to begin shooting, he showed me Christian Bale’s look in The Machinist. It was a huge challenge and I am glad it paid off in a big way.’

That apart, the film boasts top-notch performances all around, and to the credit of the director, he casts a bunch of fresh faces, which add greatly to the credibility the actors bring to their characters. ‘When I write a script, the looks of the characters automatically register in my mind. Kinjal, Arna Mukhopadhyay (who plays Amarendranath), Anuska (as Hiralal’s wife Hemangini), Tannistha Biswas (playing Kusum Kumari), Koushik (Madan’s cunning lawyer Tarini) matched my imagination. And they all are from theatre, so I didn’t need to train them from the basics.’

Then there are some knowing insights that one cannot but help chuckle at. An exasperated Kusum Kumari asks Hiralal why the latter keeps insisting on getting her wet every time he wants to film her (the birth of the eternally wet film heroine), or for that matter Madan’s understanding of the business of films: The only product of this business is dream, dream and dream (echoes of entertainment, entertainment and entertainment?). There is of course the rather alarming insinuation that Madan had something to do with the fire that destroyed all of Hiralal’s work, in the way Roy cuts from Madan insisting on being the first to create feature film in Bengal to the fire. The director says, ‘I haven’t mentioned that Madan destroyed the film. I have portrayed Madan as a proper businessman. Totally opposite of Hiralal.’ There’s also the age-old debate of the producer/director overruling a writer as seen in the falling out of Dutta and Girish Ghosh. Or the questions of a filmmaker’s creative freedom versus the producer’s clout with the distribution/exhibition, in a crackling exchange between Hiralal and Madan.

It is also hugely entertaining to see Hiralal explain the concept of a commercial to the proprietor of Jabakusum hair oil, C.K. Sen (Sankar Chakraborty). Or an elderly Muslim cajoling his wife to remove the burkha so as to partake of this new wonder - a sequence that conveys the awe of it as much as its potential, like that of the railways almost fifty years ago, to alter the social fabric of the nation with its ability to bring together all strata of society under one roof in close proximity.

I began this essay with Ebert and so it’s only fair I end it with him. As he was fond of saying, it’s not what a movie is about, but how it’s about it. There’s no denying the importance of what Hiralal is about and Arun Roy’s endeavor in that direction. As he signs off, ‘I just wanted people to know about Hiralal Sen. It’s a matter of shame for all of us that despite being the world’s largest producer of films people here haven’t even heard of him. At least now we are talking about him. That is my satisfaction’. Valid point. It’s just in how he goes about it that lays the nub. A dynamic pioneer like Hiralal could have done it with a biopic that was less static.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)