-853X543.jpg)

The Flashback Experiment

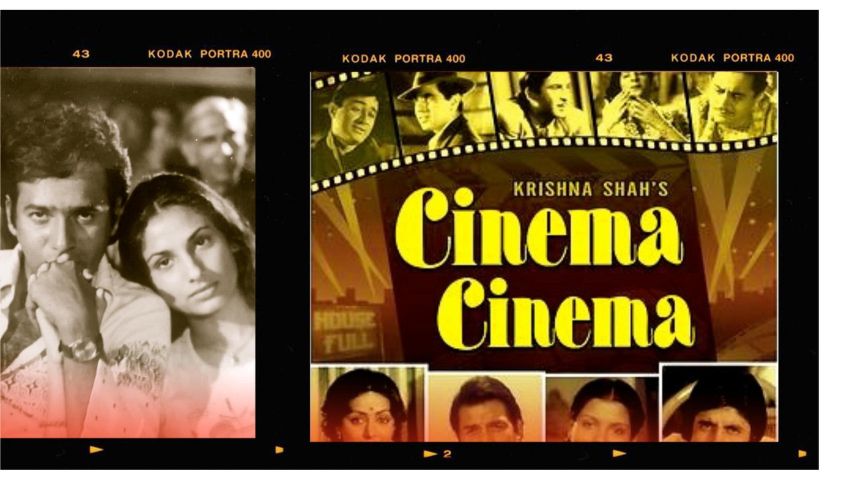

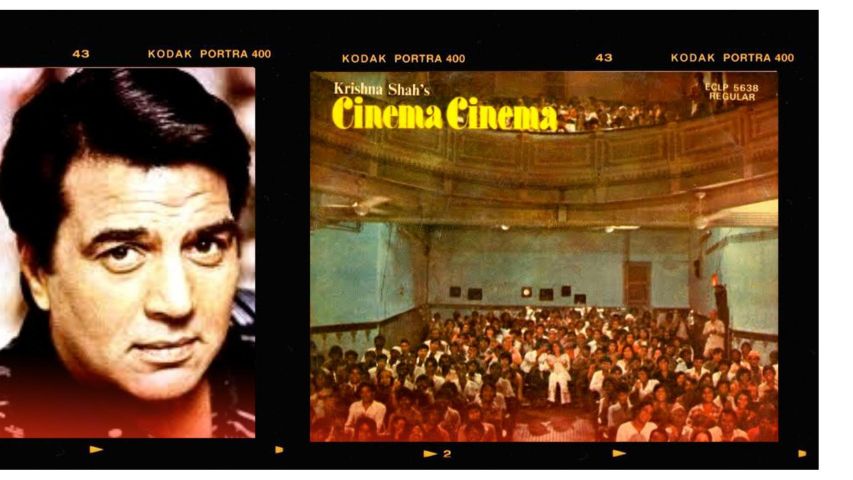

by Dhruv Somani June 27 2022, 12:00 am Estimated Reading Time: 7 mins, 42 secsFilm historian Dhruv Somani revisits Cinema Cinema, the 1979 underappreciated documentary by Krishna Shah and Shahab Ahmed, on the genesis of our popular cinema.

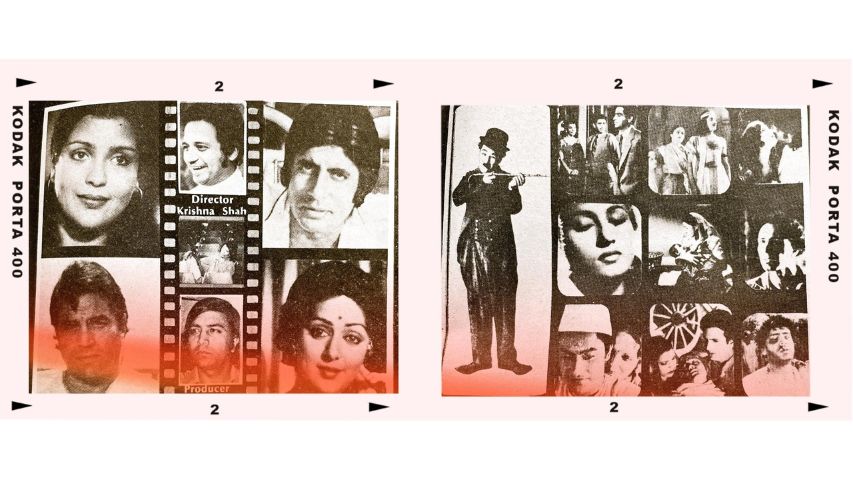

Cinema Cinema was made by director Krishna Shah (most famously known for Shalimar) in 1979 as a documentary on Indian cinema and its multifaceted dimensions. This was after two years of extensive research at the film archives all around the world.

Here was a significant attempt at a chronicle, depicted through a film showing at a ‘house full’ local single screen theatre. The audience buzzes with a variety of comments and colloquial one-liners.

The experimental venture aimed to bring to light a range of age-old barely known and obscure facts. It also stated that the dichotomy between the privileged and the underprivileged, the rural and the urban, the orthodox and the progressive, the senior and the young generation disappear the moment the lights go off in the auditorium.

The naïve viewers forget their hardships and struggles from the moment the hero bays for the villain’s blood, catalyzed by the heroine’s helplessness. Coins are thrown as the air is rent with wolf whistles when the vamp breaks into a cabaret number. And there is a collective sigh of relief and catharsis when virtue triumphs over evil.

Truly, popular cinema has been largely archetypal, often described as masala entertainment. It has tropes, stereotypes and recurrent themes to evoke the audience’s involvement and empathy with the upright hero and the heroine. That’s what Cinema Cinema was all about - a story of our popular cinema and its adoring masses.

In all, it took three years to complete. Confected by incurable cinema buffs Krishna Shah and Shahab Ahmed, delved deeply into the psyche of the cine-goer. Often movie watchers seem to be livelier and more jovial while watching their favorite film than they are in real life. The film is not only a nostalgic trip down memory lane, but meant to be a first-hand experience wherein the lines blur between the subject and object, the spectator and the onlooker. The perspectives offered were both novel and striking.

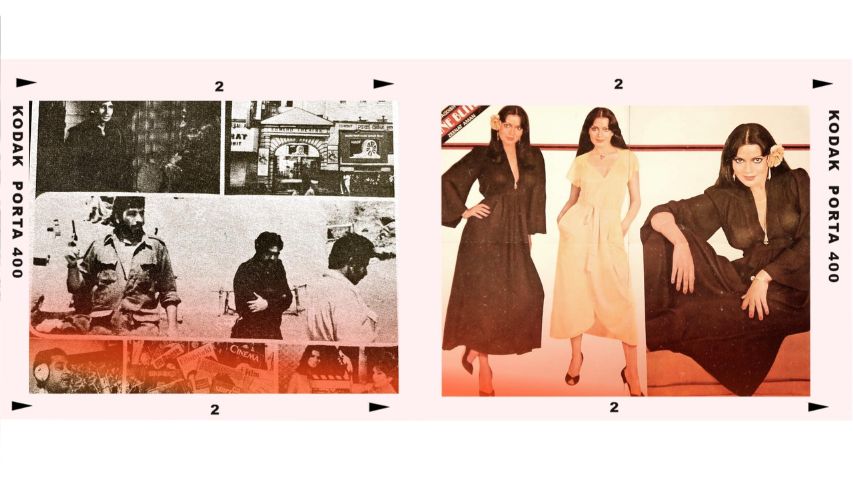

Incidentally, the extensive research was carried out at the Eastman Kodak Archives in Rochester. The legendary French archivist Henri Langlois had expressed a keen interest in the project and opened the doors of the Cinémathèque Française Paris. At the National Film Archives in Poona a treasure trove of old films was accessible.

About 500 films from the silent era to 1979 were studied out of which excerpts from about 200 films were selected. An audience of about 500 people was made to gather in an antiquated theatre where hundreds of movies were screened over two months to film their reactions. Countless producers and distributors were contacted all over India to complete the intensive research-based project.

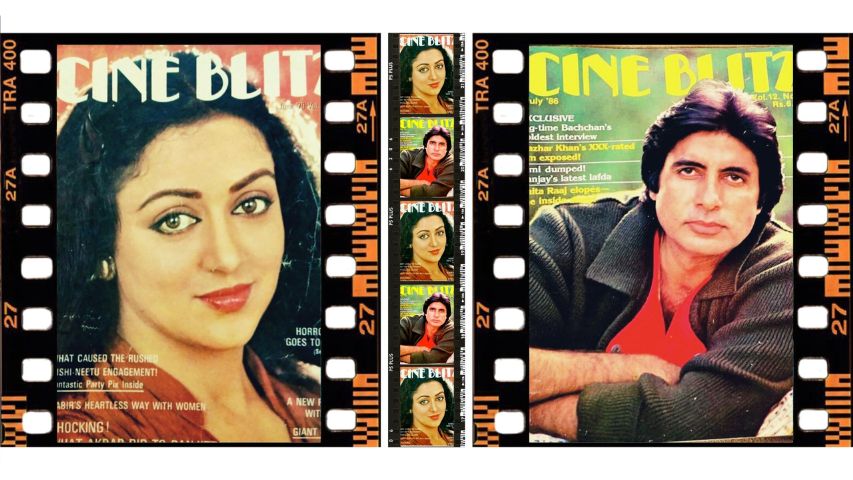

Cinema Cinema effectively conveyed the feel and the flavor of Indian cinema in a little less than two hours. Four major stars, Zeenat Aman, Hema Malini, Amitabh Bachchan and Dharmendra played the roles of narrators or intermediaries. They speak to the audiences directly about the beginnings, the trials, travails, and triumphs of Indian cinema, showing excerpts from films. But the camera of Cinema Cinema is double faced; it is as interested in the film as it is in the goings-on in the auditorium, in the theatre compound, at the refreshment counter and in the projection room.

On a Sunday afternoon when the box office opens, the tickets are sold out and black marketers do brisk business as a parallel box office. The theatre quickly fills up with a cross-section of viewers. Director Krishna Shah appears on the screen as people struggle to find their seats in the dark auditorium. Krishna Shah says that Cinema Cinema is the story of Indian cinema seen through the eyes of its audience.

Hema Malini takes over Shah’s place and the audience seems visibly excited. Hema narrates the uncanny story of the birth of Indian cinema -when it began with Dadasaheb Phalke, a printer by profession who saw Hollywood’s Life of Jesus Christ, which inspired him to the extent that he sold his printing press to study filmmaking in England.

On his return to India with a second-hand camera he wrote, produced and directed Raja Harishchandra (1913), India’s first feature film. Hema informs that all of Phalke’s films were based on traditional Hindu mythological themes and were an instant success. Although the international films of Charlie Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy and the Keystone Cops continued to flood the market, they faced stiff competition from Phalke’s Lanka Dahan (1917) and Kaliya Mardan (1919).

The screen suddenly turns violent and bloody, cutting to a shoot-out from Deewaar (1975). Amitabh Bachchan is tall, taciturn and suave. The audience livens up instantly. A college girl is shown sighing as Bachchan settles down to describe the evolution of Indian cinema through the 1930s and ‘40s. This pretty college girl seems more interested in her handsome idol than in either the film or her boyfriend.

She is shown smiling adoringly at her hero while her boyfriend sulks when Bachchan speaks of the memorable Indo-German venture, Himanshu Rai’s Light of Asia (1925), based on the life of Buddha and released in 1926. Bachchan moves on to describe the advent of sound in cinema. Jazz artist Al Jolson is shown singing the legendary Mammy followed by the hit song from Upkar (1967) Mere Desh Ki Dharti. Next, it seems that a nervous apprentice in the projection room has mixed up the order of the reels. An accidental wise move indeed as the audience breaks into applause.

The reels are sorted out marking Dharmendra’s entry. He introduces Alam Ara (1931) as an Arabian Nights fantasy, replete with 40 songs and dances. It was India’s first talkie and was a huge success. Dharmendra goes on to talk about India’s struggle for Independence and Mahatma Gandhi’s Satyagraha movement and also how patriotic films like Dr. Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani (1946) and Shaheed (1965) were highly appreciated.

A visibly moved audience watches a clip on the assassination of the Father of the Nation while Dharmendra describes the appearance of the neo-realistic films in India. Hum Log (1951), Do Bigha Zameen (1953), and Mother India (1957) were some of the memorable works, which portrayed class issues, exploitation of the poor and unemployment. Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa (1957) was the culmination of the socially concerned film. The despair and disillusionment of the unforgettable death scene from Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959) combined with memories of Guru Dutt’s own suicide leave the viewers moved to tears.

The film takes a break for an intermission as we are made to follow the spectators for their reactions in the foyer, tea stalls and even toilets as they discuss, criticise and comment on the film. The college girl and her boyfriend by now patch up their trivial quarrel since they are overwhelmed after watching the tragedy of a poet in Pyaasa.

The second-half of Cinema Cinema begins with Zeenat Aman describing how Indian cinema turned towards simplistic, escapist melodramas, replete with stock-in-trade plots in the late 1950s and ‘60s. Quintessentially masala films, they were packed with songs, dances, music and comic interludes. Earlier, with Raj Kapoor’s Awara (1948) Indian films had become more extravagant and technically slick. This trend eventually culminated in the mega-hit Sholay (1975) filmed in 70 mm with stereophonic sound. As Amjad Khan appears on the screen now, the audience is delighted, anticipating his stanzas of dialogue word by word.

A montage of the entertainers of the bygone era follows. It is pointed out that to kiss or not to kiss is a censor problem that has hassled directors for decades. The song and dance sequences are a tremendous success when the film suddenly comes to a halt. Irate spectators shout while the couple takes advantage of the situation to seal a kiss. The film is spliced together in the projection room hurriedly. Strains of Dum Maro Dum from Hare Rama Hare Krishna (1971) rent the air. The film ends there. The auditorium empties except for a man who has dozed off.

Besides the four major superstars who served as narrators, others in the cast were Kim, Mushtaque Merchant, Dinyar Contractor, Hoshidar Kambhatta, Kanchan Mattu, Sharad Bhagtani, Bobby Grewal and Bishen Khanna.

Cinema Cinema released on June 27, 1979. During my conversation with Kim (who essayed the role of the young girl) she said, ‘Ahh, Cinema Cinema, what does one say, I had an absolute whale of a time shooting it. Almost the entire film was shot at Edward Talkies of Kalbadevi Bombay. We would shoot all night after the last show, which would end by 12.30 till about 6am. Krishna Shah was a great director to work with. He was very enthusiastic and detailed with his homework. It was a documentary on about a hundred years of cinema and even though it did not do well here in India it managed to win awards in Toronto.

Alas, it was a downer at the ticket counters. Clearly, such an effort to apprise the Indian audience of its film heritage was way ahead of time.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)