Meet Barnali Ray Shukla; A Writer, Director and Poet

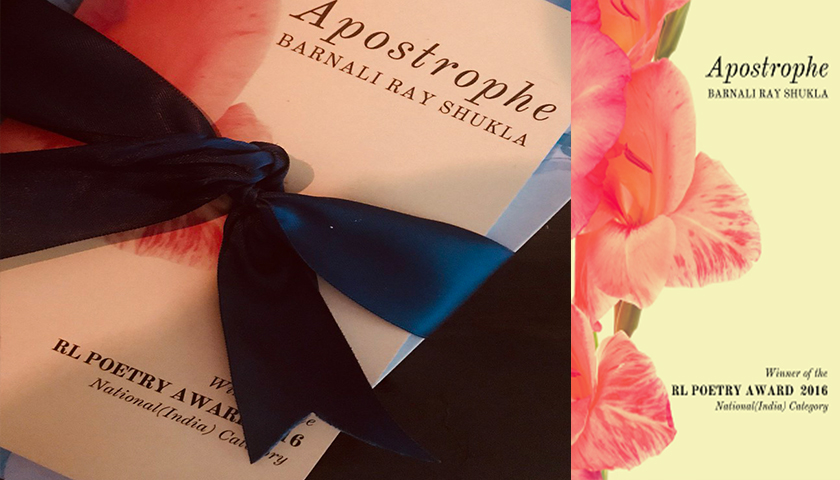

by Sukanya Sudarson June 8 2018, 4:08 pm Estimated Reading Time: 9 mins, 2 secsBarnali Ray Shukla dons many hats – that of a writer-director, a documentary filmmaker and a poet. She has worked in movies like Satya (1998) as assistant director and then in Thodi Life, Thoda Magic (2008) as writer and Kucch Luv Jaisaa (2011) as writer director. She wrote and directed the short film Miss Shoe-Bra Negi. Her documentary film Liquid Borders explores the geographical and political boundaries of India. Her first book of poems, Apostrophe, won the RL Poetry Award 2016 in the national category.

In this interesting e-conversation, Sukanya Sudarson, interviews the multifaceted and extremely talented Barnali Ray Shukla. The book launch will be held at 6:30 p.m. on June 9th, 2018 at the Prithvi House, Janki Kutir, Juhu, Mumbai.

.jpg)

Q: First, why a mutant poet?

A: Nine years back, I nearly died of wrong medical diagnosis. In this second life, all that matters is getting closer to all that is true. To create something new one has to be free. To be free, it’s important to let go of fears of expectations and compulsions, prescribed by the rest of the world. And this, is the mutant speaking. And that word poet, is a big word, I don’t let the four alphabets get to my head. Having published poems doesn’t make one a poet, am learning.

Q: From being a microbiology student to becoming a mutant poet, how has your journey been?

A: Unfortunately, I was a topper both at graduation and post-graduation, was charting out the best route to USA with ridiculously high scores in GRE. It was all very heady. I was excited about the pursuit of biotechnology but then a debate came by. I paused when I was hit by the idea of this upcoming debate.

I had to pitch the ills of biotechnology. That felt insane. I was always in favour of progress in this field and in awe of biotechnology. My professors were sure the narrative had to be subversive, while they coached the rest on the merits of the field. While I was stung by the challenge, I thought my teachers were all dinosaurs. Doomed and outdated. I felt let down, I had treasured my teachers. To top it, The Miranda House debating-society was merciless. I had to get headlong into it like working on a thesis on a doctoral level.

Kaboom! I was exposed to a mine-field of terrifying realities of this field. Bio-ethics was the new mantra for anyone with a conscience. The most-prolific and successful Bio-Tech companies were exposing countries in Asia, South America, Africa to all possible perils in the most unethical ways. So working for the USA was out.

It wasn’t just one debate that changed my plans overnight. In my final term at the university, I was beginning to get skeptical of the empirical nature of science. The stripping bare of all that was matter, to its last unit. That wasn’t the picture of the life that I wanted to make in my corner of the world. It was my personal break-up with the formal study of science.

At 22, I didn’t have existential crisis but I didn’t want to grow up saying “Its finally all carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. Everything else is an opinion!”

Thus my secret life with the Humanities began, not formally.

Q: After breaking up with science, you have worked on full-fledged movies, explored the short film genre, travelled for the documentaries and seen the television world too; does any one of these experiences take precedence over the others? And tell us why?

A: They are all sovereign. They stand on their own and yet extend themselves to every mode of expression, when you want them to. In practice, there is nothing watertight. To the fiction writer, poetry is omnipresent. To the documentarian, imagery is an ally. To speak in short-fiction, clarity is imperative.

It’s the plural identity of any auteur that makes this cross-border travel, accessible.

Movies are a result of many forces, visible and invisible. More often than not, movies are most susceptible as they draw heavily on resources. There are many battles to be won for that one big war but finally when it comes around, gets seen, gets recognition, the value is supreme. Stakes are high. The heartache can be intense so lows are dismal and the highs, so heady…that can be euphoric.

The short-film is a fabulous format to work with but we here are still divided on this. Working on this gets reduced to a hobby, sooner than later.

With incredible leaps in digital technology, access to a decent camera has become easy. Post-production can be achieved with much lesser paraphernalia now, as compared to dealing with the ‘rushes’ to ‘married-print’, on celluloid. This has created an unstoppable breed of stories floating as films. The friendliness of digital technology allows flexibility and reach, but sometimes we need to hold our horses, to be able to make an impact.

Documentary filmmaking, however, has reached a new high. Back home, we are a bit apprehensive of this form but most documentary-filmmakers are innovative, fearless, restless and most certainly have a fine social-conscience and oodles of subdued swag.

But then the Achilles heel is universal, finding funds to make documentaries and eventual outreach, both are inconsequential, hardly taking it close to the ears of any industry. In India, the director doesn’t even put his/ her name in the budget proposal, if at all a pitch is made. This makes this format, most vulnerable to abandonment.

Television is omnipresent but fast-losing ground to the web. In India, entertainment programming in fiction, has lately done a lot of damage to the way an entire generation has been growing up. As for me, I was lucky to have collaborated with new minds and also with the Big ‘Ben’ of it all. The soaps. But thanks to television many have material comforts and millions of Instagram followers, the success quotient for most millennials.

Q: You had said in an interview, “…the fish don’t really care, so why do we?”. From your experience while making your documentary Liquid Borders, why do you think ‘people really care’ that borders exist?

A: Those were the words of Robert, a fisherman, whom we met in coastal Tamil Nadu, 11 nautical miles off the Lanka ‘border’, in the Bay of Bengal. He and his fellow-fishermen have been writing letters to Prime Ministers. Our footage would reveal that he has written to Mr Manmohan Singh and to Mr Narendra Modi. And he awaits a response. Robert and his friends haven’t heard from anyone.

He voices what their fraternity is perplexed about, the meaning of borders and says “we have to follow the fish, the fish wont follow us, and then people say we are breaking borders, what do we do?”

In a politically correct world, there will be borders. Politics at most times is mediated reality. People at borders are at the mercy of a lot more than just policies. Living on the edge isn’t easy.

There was a lot of life-learning while making ‘Liquid Borders’. Lot of questions that came up and are still being answered. During the making, a lot many times, I thought we will never make our film but yes, we didn’t give up. This film went far and tends to start new dialogue wherever it goes. It still keeps travelling and making new friends and foes.

Source :Twitter

Q: Your first book of poems ‘Apostrophe’ won the RL Poetry Award for 2016, what was the feeling like to be recognized and appreciated for something that you love doing?

A: I feel grateful. And was truly surprised. Quite like my M.Sc scores.

On the day of M.Sc results, I remember hiding. My bestie told me I had topped. I was scared to go and find out in person.

Times have changed, result of the RL Poetry Prize was on social-media before I knew the results. I was tagged on Twitter but I was off-the-grid in the Christmas week. We were at a friends’ farm, looking at their new strawberry crop. It was only three days later when we came into ‘range’, did I know I had won. To be precise it was a coffee-shop on the Mumbai-Pune Expressway, where I was sitting with a large cup of Latte and my phone sprang to life. And I was about 80 hours late in seeing the joyful news. My manuscript was selected as the ‘India winner’ of this Award. The reward was the book coming to life. Considering there were many manuscripts in the reckoning, am happy that my manuscript was chosen and sees this day. ‘Apostrophe’ is my first book of poems.

Q: Looks like you love travelling to the mountains, does nature inspire you to write?

A: Up, close and personal…mountains are most challenging. Just when you think you’ve got the hang of at least a fraction of it, they throw up a new challenge. It really gets around to being closer to the little things that one cant do without. It is about what really matters. Otherwise we tend to carry a lot of baggage that weighs us down. Mountains make you resilient, humble and inclusive. Perhaps creative.

Q: Which hat is Barnali donning next – that of a filmmaker-director, writer or a poet?

A: I have been working on a book which I can’t talk about yet. This new book entails a lot of research and has been most challenging so far. Am thrilled it is coming to life.

Post that birth, I shall complete the editing of my second documentary and get to the dialogue-draft of my next feature-film. Poetry however always remains.

Q: Will you give us a peek into your book being launched on 9th June? What’s it about?

A: ‘Apostrophe’ explores the possibilities of belonging. The capers of something so minute that normally goes unnoticed. This is possibly a central drive for most of my work where I want to lend a voice to the ones who will rarely speak up for themselves. You will also notice an exploration of parallel worlds and maybe some disregard for stereotype.

Q: Any ‘words of hope’ for the dreamers?

A: In our times, idealism is a huge luxury but dreamers can afford it.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)