A CUT above the rest…

by Vinta Nanda April 11 2019, 9:11 pm Estimated Reading Time: 19 mins, 46 secsMy friendship with her is deep.

She's a feminist and the most expressive among most whom I know.

She's probably the only writer I've read who lures you by her storytelling and transports you into a world where she then abandons you. She leaves your hand the moment she knows you'll be fine on your own and that you'll find your way out of her fiction when you desire to exit the experience.

In this interview she talks about everything about herself to me. I'm going to leave it here and let you discover her, like I did.

Happy reading!

Q: I’m curious to know about your childhood, your years growing up and your days in college at Jadavpur University?

A: I grew up an intensely lonely child in a sprawling ancestral home in Kolkata, the city of my birth, after my mother, a young widow returned to her parental home, post my father’s suicide. Baba suffered from Schizophrenia. I saw my mother, a young, silently resilient widow being stigmatised by the nature of his death about which and over which there hung a cloud of suspended, suffocating silence, for years, shunned from family functions, like weddings and baby showers, where her presence was considered inauspicious. We had no pictures of Baba, except a grim looking, sepia stained photograph in our puja room – where he stood, distant, like the line of Gods and Goddesses we prostrated before and prayed to, daily, sans ever knowing them, intimately.

I wrote imaginary letters to my father, which perhaps was my first works of creative writing. Baba felt safe. He was my secret. A place of refuge and running away, in equal measure. I grew up an obese, buck toothed kid who lied compulsively to avoid being bullied in school and who wasn’t ever the centre of a man’s attention, or affection. I was always exceptionally bright in academics and also extra curricular activities and also school captain – which now I feel, in hindsight were my saving graces. After topping my Board exams in twelfth, I joined History Honors in Jadavpur University and honestly, after the convent school strictly all girls sort of set up – suddenly my universe expanded. What I most enjoyed about my years there – my BA and MA, five years in total was my involvement with student politics – we formed the first ever Jadavapur University Students’ Federation that defeated the SFI and were passionately involved in bettering the lot of students, facilitating women’s safety on the campus, ensuring the premises was well lit, that hostels were safe spaces, that sexual harassment cells operated unbiasedly and that students and teachers collaborated on matters sans violence/resentment, outside of their power and peer structures.

College also symbolised a time of personal growth and learning for me – I underwent my first gynaecological surgery to remove an ovarian cyst at age 19 and a drastic weight loss – post which and suddenly, emotionally unprepared as I was, I found myself in a relationship. My first boyfriend was a stalker and emotionally and physically abusive. My body which had been my bane – now held me captive like a fortress – I was alien to its newfound sexual awakening, in more ways than one. I wanted to be loved so deeply, that I feared losing it. Struggling with finding my own voice, I tolerated and suffered his toxicity – before forsaking an Inlak Scholarship to study in Oxford, instead taking up a job in New Delhi at The Asian Age, just to escape him. And my heart. Running away, at 21, felt like the right thing.

What I did not know, was that I could never run away from shadows. You can never win against your own demons.

Q: From your debut as an author to Faraway Music, Sita’s Curse, You’ve Got The Wrong Girl, Status Single to now Cut, tell me about this progressive journey, how it has made you who you are today?

A: I wrote Faraway Music – that in more ways than one and like many a debut novel was autobiographical as an outpouring that was spontaneous and self effacing – parts of it scribbled when I was working in Mumbai heading the Lifetstyle beat in The Bombay Times. That was in 2013 and now sitting as I am answering this in 2019 – I think in this long six year walk that I began frankly because though I was earning a helluva lot of money as a high flying Vice President of a PR outfit in Delhi, I felt that something was amiss in my life – I wanted more – and though even my own mother was disapproving when I quit a full time job, I plunged headlong into finishing the book that I realised had by then birthed itself inside me. And was restless to see the light of the world outside.

I had no idea back then that I would become a full time writer. In fact, Sita’s Curse, my second and critically acclaimed and bestselling feminist erotica also just stumbled out of me one night, and the rest flowed very organically. While I was writing Sita’s Curse and because I have a habit of sharing extracts of my book on social media where I was amassing a large following, I was contacted by a woman from Jaipur, who I shall call Neeti, for the sake of protecting her privacy. Neeti was married at 16 to a man three times her age, in a perfunctory business deal by her Marwari businessman father who had three more obese, dark, and unqualified daughters to wed. Neeti – who was raped by her husband, on her wedding night itself, her hands tied to the bedpost, as he whipped her breasts and stomach, before turning her around forcefully and massaging his privates over her back and buttocks, hoping to achieve an erection which he couldn’t, before he slapped her hard, many times, thereafter, actually, before passing out drunk over her naked, whimpering body, urinating on her sex. Neeti – who at 20 and after she naturally failed to conceive was paraded to a Guruji who would ‘bless her womb’ – and who, under the guise of religion and holy hocus pocus, raped her again, albeit with the consent of her in-laws, and, aided by Neeti’s own shameful silence and innate fear of being labelled a ‘baanjh,’ alongside, the promise that so many Indian daughters make secretly when they throw a fistful of rice over their slim, unsure shoulders weighed heavy under ornate bridal finery, leaving the sanctimonious lakshman rekha of her parent’s home and becoming what is her destiny – paraya dhan. Never to return. Come what may.

‘I want to breathe, Didi…’ she whispered as we parted, ‘my whole life I have lived like a bird in a golden cage – my body, my desires, my child, my womb, my fate, someone else’s becoming…’ Her words transformed my life purpose, as I finished writing Sita’s Curse that was to become a haunting treatise of female sexuality that explored familiar darkness that Indian families despised and deliberately covered up – marital rape, the topic of male infertility and erectile dysfunction, the physicality and sexual desires of a middle aged, middle class, housewife, whom I called, Mrs. Meera Patel who lived in a stuffy Byculla chawl, sexual exploitation at the hands of organised religion, women and pornography and paid sex with a gigolo and finally and what I believe is the cornerstone of my writing and my personal belief system – the owning of one’s individuality and the non negotiation of one’s aspirations, sexual affiliations and professional and personal dreams.

You’ve got the Wrong Girl! My third fiction novel was born out of a consistent demand by my younger readers, and a lot of younger male fans, who said they would love a book that talked to them, directly. As a writer and during the phase that I wrote Sita’s Curse, I had been immersed in reading a lot of Kalidasa and the Abhigyanam Shakuntalam was a consistent favourite. So, I asked myself, what if, all the things stereotypically ascribed to women in love – happens to a man and what if an Indian woman writes a lad lit – again a genre that is barely touched upon in this country. Dushyant, mine, that is, remains one of my most affable characters – and the jungle of Kalidasa was the urban jungle of Kolkata, set in a bustling red light area, Sonagachi, the largest red light area of South Asia. It was fun rewriting the gender rules, to make Dushyant a flawed and yet real man – who is as confused as he’s confident, as scarred as he’s successful. As lonely as he’s popular. To glimpse into his mind – and to make him question the notion of love in all its myriad splendour – YGTWG was perhaps one of my happiest books that exposed a side of me that is not very often revealed in my writing – that borders on noir – that I am a rebel romantic.

Status Single, my first non fiction that appeared last year was an amalgamation of stories I had listened to from divorced/separated/abandoned women friends, single mothers, many of them, their struggles close to my mother’s before she found love again in her life with a man 14 years younger than her. My own life story – of being a woman who craved marriage and motherhood, whose dreams were wrecked thanks to a broken engagement in her early 20s – and who rebuilt her life from the ashes, embracing the difficult and diffident reality of her own trajectory – single, 41, fostering a child, caregiver to aging parents, battling an auto immune disorder, Fibromyalgia. The way 74 million Indian women now soldier on – Status Single and the community I founded online – vis a via the interviews I conducted with 3000 urban single women across the length and breath of this nation over a time span of a year – changed me the way Sita’s Curse had. I dream of organising the country’s first single woman summit later this year, in Bangalore, for which I am currently fund raising.

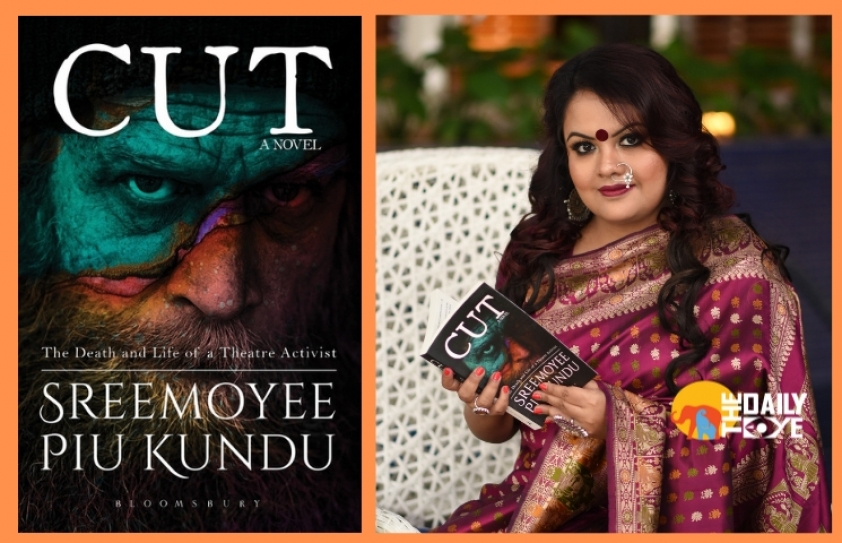

Cut being published by Bloomsbury India is my fifth and most ambitious novel that if I can draw a cinema parallel could be comparable to a biopic on the death and life of Marathi stage thespian, Amitabh Kulashreshtra. The character of Kulashreshtra I drew from a real life happening that scared and stayed on in my memory – way back in 2004, when I resided and worked in Mumbai as a Lifestyle Editor, and was a regular watcher of Marathi plays. A small news snippet in the regional dailies caught my attention, one day. A small time Marathi tamasha kalakaar, who once ruled the stage and the hearts of his audience and who had fallen into disrepute thanks to his loss of memory, deafness and debauch drunkenness, was found dead, under mysterious circumstances on a local train, having boarded the ladies’ coupe. There were many theories that floated about his accidental almost dishonourable death – ranging from character assassination, to him being an alleged terrorist, to even accusations that he attempted to pick pocket a woman’s purse and how he was intoxicated and couldn’t even recall his name. The way his body lay unclaimed at the Mumbai hospital morgue haunted me for days and the way the local Marathi channels kicked up the dust on his death – painting him in so many shades – his personal life was dug into, and dissected. His political affiliations – his parents who were Muslim and Hindu, respectively. What was conveniently forgotten and brushed under the carpet was his career and contribution to regional theatre – his character roles that defined the ordinariness of the middle class in Mumbai – how political satire was what it was, because he spoke on the behalf of the ubiquitous people he caricatured and essayed.

It was a tragedy of being in the limelight, for me, and, also the bitter price he had paid, when his life with advancing age came to be swallowed by the shadows of the medium itself being swallowed by sleek supper theatre that naturally attracted more elite audiences, the advent of Bollywood and more mass forms of entertainment and his outspokenness and chequered personal life.

Cut is a tribute to theatre, as much as it is to the theatrewala – its inspiration is the stage, and the backstage. The lights and the dimness. The way lives form and melt. Its backdrop is as much this country itself – its soul, and its suffering – the riots of 1992, in the aftermath of the Babri Masjid demolition, the thread of communal politics, the way the independent artist is being targeted as Urban Naxal – where dissent is viewed and portrayed as sedition.

Every book I have written has been born out of my soul – has coloured my conscience the way it shall always bear the colour of my conscience.

Q: How does your journalism impact you as an author?

A: Apart from being a full time writer, I am also a columnist on gender and sexuality and I regularly write columns, and in that work, my journalistic DNA is what comes to the forefront. Extensive research, collating data and interviewing women, mainly, is what I do – apart from analysis and fact checking. I think, be it writing books or columns, storytelling runs in my blood. It is who I am and my lens to view the world – it is my only truth, and my closest alibi. It is how I want to be remembered. Also, one more important contribution of journalism has been my relationship with people close to the ground – I love collecting stories of real life, ordinary folk – I am always observing people – and this can also probably be attributed to my growing up, intensely alone, like a fly on the wall, always seeing things as an outsider. There is a part of me that will always seek to tell the truth – the truth of the marginalised, the truth of the oppressed classes, the truth of sexual violence and gender disparity, the truth of our scars and all our other lies – the places where India hides.

Q: What are your thoughts about where Indian women are today?

A: Women in India occupy a diverse landscape, thanks to the wide socio economic parity that exists between the classes. So, while I feel that there has been a lot of economic empowerment of women, thanks to girls being educated by families, at least till graduation (that is seen as a basic criterion of marriage, perhaps,), more women, hailing from smaller towns and tier two and three cities living outside their family structures, either in paying guest accommodations/rented apartments, earning their own keep, sending money home to their parents and siblings – being the primary bread winner in many cases, too – women being more confident of their choices, emboldened by the freedom of being financially secure – a lot more women marrying later, completing professional degrees and wanting a job before a prospective groom – more sexual experimentation thanks to the surge of dating apps, the technology boom and again the freedom of living solo, not being answerable to family – ditching traditional arranged marriages and picking their own partners – being able to live in/indulge in same sex equations, buy their own homes and cars. Travel across the world – there is undoubtedly a feminist revolution, on whose brink we are poised.

And, yet, even as so much changes and undoubtedly for the better, there is still the darkness of Khap Panchayats, acid attacks, gang rapes, child sex abuse, marital rape and domestic violence and women suffering in stoic silence for fear of societal stigma and shaming. For women being forced into marriages and motherhood – child birth hardly ever a woman’s own free choice – our womb is our destiny, still. So, my feelings about my own sex escalate between celebration to cringing at how every generation still dwells in the same dark shadows, and I guess that is the whole point – that on the edifice of our daily battles – upon our victories, sometimes, lopsided and half hearted, and in our most intimate spaces – we will be again called to wage the same war. Time after time…

Q: Do you feel the difference between yourself and your kind and women from higher economic status as well as women in weaker positions that you are in? Elaborate please?

A: Yes, there is a lot of difference, as I earlier stated. And, if feminism has to make sense in the times we are now, there has to be an intersectional, more inclusive, larger goal oriented, version that we must now decipher and dwell upon. My house help, who is beaten by her husband, a drunk, debauch rural musician who she has run away from twice and who using the compulsions of the village Panchayat has managed to get her back – also her father is too poor to feed an extra set of mouths, the brothers, all married couldn’t care less – today has a bank account, a health insurance and an Aadhar card – she also sends her son and daughter to a village government school. But, can she leave her husband. No. I think women in urban, progressive, middle/upper middle class families have more choice – also as there is less intervention from extended families in an era of independent nuclear family structures, girls working and educated – they are more exposed and thus can afford to stand their own ground. So, yes, there is ideally a lot of difference.

However, when I see many of my own married friends languishing in emotionally and sexually dysfunctional relationships, working, urban, qualified women, who stay on, citing their children’s future or just afraid of upsetting the apple cart – of their parent’s losing face – of their fathers having splurged lakhs and lakhs on a big, fat Indian wedding and thus them being petrified of facing the family – of being labelled a ‘divorced’ woman and because of the stigma and stereotyping of a single woman in a society that venerates and socially sanctions marriage and motherhood as legitimate – I feel as a gender binary, maybe, at a very deep and central level – our trajectories are ironically similar, and, that we fight the same battles, with varying levels of aggression.

Q: Do all the distractions (social media, etc.) today add to your expression or take away from it? How do you deal with them?

A: I find social media fake and cacophonous, on most days, but, I use it for my writing, to share articles on topics and causes I espouse and for my own activism. When I am writing a novel, I am completely reclusive, and don’t leave the place where I am writing for months – I hibernate and honestly that is truly my happy spot. The problem with social media and our constant over exposure to the medium is that we often live in a bubble where we live our lives by someone else’s standard, constantly. And that I find utterly superficial.

1.jpg)

However, in certain and extremely significant matters, such as the recent #MeToo campaign, for instance, social media abled women who were geographically disconnected to unite for a globally critical cause that needed vocalisation and verbalisation – I am convinced and this I say, with relation to social media, per say, whether I see women sharing sari pictures or forming a single parent/single woman community/pact, airing their opinions fearlessly, sharing articles and photographs – there is a pattern of us as a sex coming together – and this global movement I feel finds expression on social media, more than anywhere else. I use my FB as my personal blog, being tech challenged and not really being on Twitter and using Insta more for my personal pictures, to speak my truth and the platform though infiltrated by right wingers and religious fundamentalists – also has shown me that words and emotions and humanity is the strongest and most fundamental trigger point and that I find very heartening.

Q: Your thoughts on why women aren't able to stand up for each other and support each other?

A: Actually, here I have a slightly different take. Yes, women are jealous and backstab and bitch and are jealous creatures, but aren’t men too? I mean, if we study mythology, and history, most wars have culminated in fratricide, where women and their bodies and honour have been used as a pawn – I think for all the same sex negativity that perhaps stems from personal insecurity which I attribute to people in general, and, not really a woman or a man, as these are more human emotions, I feel women more than before are standing by each other and taking up for one another – be it a sari pact or online platforms like Ladies Finger or various other feminist forums – the time is now for India to witness an unprecedented wave of women rising up to take their rightful place under the Sun. The future is female. And yes, while we all practice perhaps a certain variant of feminism the way our personal trajectory is diverse, we are marching towards a tomorrow where women will fight not just patriarchy but also the kind of matriarchy that acts as gate keepers of misogyny and female subordination.

Q: Are women following traditional rules more independent than those who are writing the rules?

A: Women following traditional rules cannot be more independent, because rules I believe are meant to be rewritten in keeping with the environment we inhabit, our constant occupational hazards and our larger gender battles – so those who prefer to remain in chains are doing so at their own risk. I am often told that urban women are better off, in terms of empowerment – but as I said earlier, I think in more ways than one – we are the same – and while every single generation reaps the fruits of victories of their female predecessors, we must again fight some of the same battles – because our place vis a via a man is always going to be challenged and not won sans a legit fight – that may involve us taking on society, families, businesses, bosses, lovers, parents, children and even our own sisters.

Q: What would you say to women in media and entertainment? Especially those starting out now?

A: Don’t stop owning your own voice – ever and be prepared to be the lone wolf, if pursuing your individual truth and standing your own ground is your goal in life. Be prepared to be criticized. To leave jobs and perhaps even switch professional gears – to be your own saviour, because the world is innately unfair. Be uncompromising where ethics go. And never be silenced. You will be heard.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)