India’s Biggest Challenge will be to address Modern Poverty

by Yash Saboo July 11 2018, 3:55 pm Estimated Reading Time: 2 mins, 39 secsLast September, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation released its annual Goalkeeper’s report, highlighting the extraordinary progress made in reducing extreme poverty around the world, while also warning that sustaining this progress would not be easy. The data shows some serious reduction in poverty rates, especially in India but poses an alarm for countries like Africa, who haven't performed well when it comes to the goal of removing poverty altogether from the country.

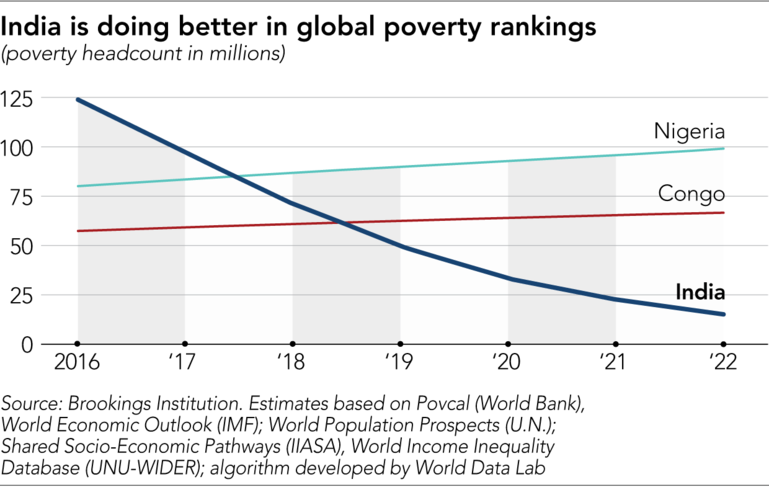

According to the Brookings Institution's projections, Nigeria has already overtaken India as the country with the largest number of extreme poor in early 2018, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo could soon take over the number 2 spot (Figure 1 below). At the end of May 2018, their trajectories suggest that Nigeria had about 87 million people in extreme poverty, compared with India’s 73 million. What is more, extreme poverty in Nigeria is growing by six people every minute, while poverty in India continues to fall. In fact, by the end of 2018 in Africa as a whole, there will probably be about 3.2 million more people living in extreme poverty than there is today. The number of Indians living in poverty is falling rapidly -- from 125 million in 2016 to around 75 million today, to 20 million in 2022, and then dropping to near zero not long after.

India Poverty Line -Brookings Institution

Already, Africans account for about two-thirds of the world’s extreme poor. If current trends persist, they will account for nine-tenths by 2030. Fourteen out of 18 countries in the world—where the number of extreme poor is rising—are in Africa.

The results from India are remarkable. Eliminating poverty in the country is India's (one of the) biggest problems and achieving such good results shows what the country is capable of. But it's not all good. Some caution is needed here. Many of those who have officially "escaped" poverty still live precarious and grim lives dogged by ignorance and disease. This is a group for whom slipping backward into absolute poverty often remains a major risk too.

In a deeper sense, India's progress raises a conundrum because its impressive record of absolute poverty reduction looks rather less impressive when measured by fuller measures of human development. Progress on issues such as maternal health or child mortality has typically been better in less successful countries like Bangladesh or Nepal, a point made by Nobel laureate Amartya Sen.

Another thing to think about is that Indian inequality has rocketed over the last two decades. As mentioned by James Crabtree in his latest book ‘The Billionaire Raj’, India's top 10% of earners now take 55% of national income each year, up from 32% in 1980. The bottom 50% have seen their share decline from 23% to 15%, with the very poorest doing worst of all.

India's poorest have benefited from the country's new economic model, but nothing like as much as the rich -- a trend which is likely to store up problems for the future, given those countries which start out their development with yawning inequality find it much harder to correct it later.

Still, absolute poverty reduction is genuinely worth celebrating. Many African nations can only dream of making rapid Indian-style progress.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)