ABOUT BRINGING GURU DUTT TO BENGALI READERS

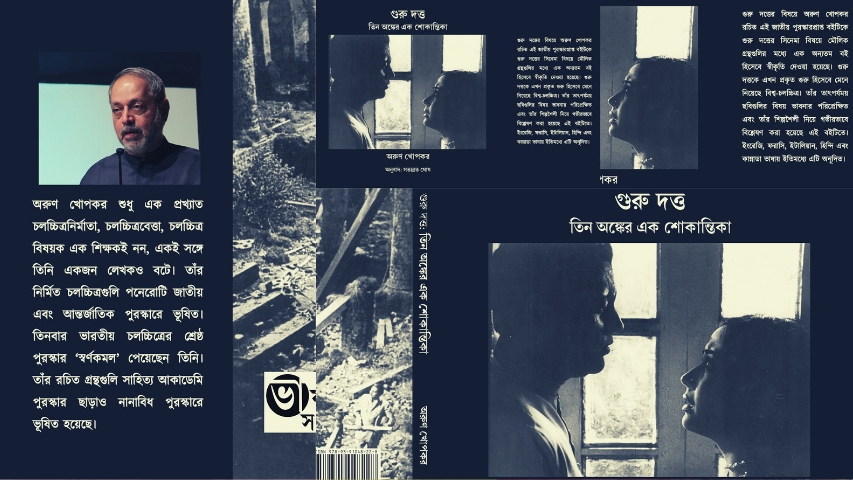

by Satyabrata Ghosh January 28 2023, 12:00 am Estimated Reading Time: 11 mins, 39 secsSatyabrata Ghosh shares the process it took to translate in Bengali the works of Nishikant Thakar and Arun Khopkar for Guru Dutt: Teen Onker Ek Shokantika.

The end: It could have been just another late morning. The deep slumber cut by the shrill ringtone. The call was from Bitasta Ghoshal, my publisher. A glance at her name, I woke up wide. She didn’t mince words, “Look, I mailed you the final print file this morning. The press will no longer accept our print order if you do not approve it within half an hour.” Logging into the mail and downloading the file took no time. And when browsing the pages a glaring mistake stared at me. All the captions of stills from Kagaz Ke Phool had the year of its release wrong.

I called the person who set the pages. “Santu, please change the year of all captions in those pages having stills of Kagaz Ke Phool. It isn’t 1962, but 1959, 1-9-5-9.” As I continued scanning the pages on the screen, they looked all right, or did they? The end line was drawn.

Guru Dutt: Teen Onker Ek Shokantika is now on the way to being born from Nishikanth Thakar’s Guru Dutt: Teen Ankiya Trasdi, the Hindi translation of the Marathi book Guru Dutt: Teen Anki Shokantika, authored by Arun Khopkar in 1986.

If emotions have ruled, yes, the 10th of January, 2023, should have been a red-letter day for me. But then some questions kept gnawing at my mind, and I became busy sorting them out. It was time to look back. Did I find those books or did the books find me?

More importantly, is Guru Dutt so important as a filmmaker to me? Yes, he certainly is. From Uday Shankar’s dance institute in Almora, he entered the film world as an assistant choreographer and evolved to the level of an auteur. He etched his name indelibly among cinephiles across the world while failing in glory to attain the stature of Ritwik Kumar Ghatak or a Satyajit Ray.

He had the tenacity to deliver marketable goods during the first phase of his filmmaking career, in camaraderie with Dev Anand. And then he faced the lens as the main character in comedy films like Aar Paar (1954), and Mr & Mrs 55 (1955). In spite of being young, he found a way to win people’s hearts but then his persona metamorphosed into something more complex and deep.

Guru Dutt had written a story Kasmakash, once upon a time, dealing with the failed love of a poet. Was it a venting of his emotion watching the family of the sweetheart of his dear friend refusing to marry their daughter to a man yet to be financially dependable? Lore may have the answer and it might know the names of the characters in that tragedy too, but then a bigger question emerged when I read this couplet penned by Sahir Ludhianvi: Go humse jagti rahi yeh tej-gam umr/Khwabon ke ashre pe kaati ta umr (Only possibilities kept me awake amid the gloomy years/The whole life is spent sheltered in a dream).

Guru Dutt relived his story and even used Kashmakash as the working title of the film script he was developing with Abrar Alvi. At the production stage, while Guru Dutt and V.K. Murthy collaborated to bring the vision of Pyasa (1957) to the screen, Sahir Ludhiyanvi evoked the painful and raging words for the film.

Watching Pyasa first on television became an unforgettable experience for me. Often it is said that silence is golden. But hearing what the poet Vijay speaks in Pyasa lent me the answer to why the lab technicians of the analogue film referred to a final positive print as a ‘married print’ after processing the optical sound negative and film negatives into one. This was also, coincidentally, in the mid-1980s when Arun Khopkar was crystalising his thoughts at Ashish Rajadhakshya’s flat in Bombay about Guru Dutt, the auteur into pages.

The other aspect that drew my attention was the familiar setting of Calcutta, which is evident in Pyasa, a film which essentially deals with Urdu poetry. Though Ghalib came to the city in his lifetime, Urdu Mushairas have never been popular events among the wide cross-section of Calcutta’s population. We have Recitation Festivals in cultural complexes and lanes of the city where the young and old recite Bengali poems of Rabindranath Tagore, Jibanananda Das et al, in similar zest and modulating voices, but public attention to poems stops there traditionally.

One reason for Guru Dutt’s affinity with Bangla and the city of Calcutta is also his lingering to his childhood days and formative years with Uday Shankar, the modern dance maestro. These were hindsight, which I gathered later. But at that point in time my curiosity about his films Kagaz Ke Phool and Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam became obvious.

Much later, I was amazed when I learnt Sahir Ludhianvi stopped collaborating with Guru Dutt after he reluctantly penned the song “Hum aapki aankhon me is dil ko basa le to” when the director of Pyasa acted more as the film producer, insisting on a love duet to ensure the box office. Though in the latter two films in purview, Kaifi Azmi and Shakeel Badayuni respectively captured the moods the auteur Guru Dutt had envisioned. Sahir was sorely missed.

This complex equation between Guru Dutt’s oeuvre and the commerce of the then-Hindi film industry intrigues me to delve more into his creative world. I could never fathom the master’s mind, which dared as well as vacillated from time to time. I do however revere Guru Dutt for his gut to discover and help to escalate the innovative energy of his cinematographer V K Murthy, who painted with lights and shadows an exemplary height. But there was actually more, which drew me towards Arun Khopkar’s book.

The Beginning: Way back in August 2000, I borrowed Guru Dutt – Teen Ankiya Trasdi. On the verge of leaving a job and a relationship behind, a tattered me started turning its pages late at night. Before the words, the black and white images pulled me in.

I did not start reading right away. But I was at it before the next day broke. The chirping of early birds brought me back to my pillow. Another night ended without sleep. I got up and dressed. My mother, a habitual early riser, was anxious. “Let me see how dawn looks,” I assured her. Ours was an old one-story house, with a cramped room, badly in need of repair. It played a major role later.

As the first light seeped through the grey sky, I looked up and found my eyes singed. Was I crying? I must have been. Because, in those few early chapters that I read in the book, I found the language that I had been in quest for. Arun Khopkar in his book had triggered something in me to pierce the veneer of romanticism I was inflicted with. Finding myself in the middle of nowhere, I decided to read the book first.

This reading, however, would not be passive. Instinctively, I decided to translate the book. This would also mean that I needed to be in Arun Khopkar’s shoes, as I never envisioned myself as a translator. As I proceeded, strangely I found the author was speaking to me in a language – familiar and simple, far from the jargon-mongering world of film appreciation I was a part of at Chitrabani (a Jesuit Church-managed Film Study Centre then headed by Father Gaston Roberge).

The centre then was resonating the jargon found in the western scholarly books about films. The environment there propelled parroting the explanations of David Bordwell, James Monaco and other film scholars. These were punctuated with ideas irreverently lifted from Roland Barthes’s book on semiology and Jacques Derrida’s theory of deconstruction as a daily habit. Most of my colleagues in the faculty and the aspiring students and theorists were desperately matching their EQs with that of the erudition in the West. Anything that was not recognized by western scholars, was not worth their time. There were hardly any conversations that could be as passionate as my ardour to watch Indian movies in a simple jargon-free language. So, at the end of the day, was I wrong as the then cinephiles treated me as an outcast there too?

And strangely, I found myself in tandem with the book beside my pillow, which also was my desk to scribble on since my student days. As I proceeded with the Bengali translation of the book unofficially, I felt a solace, which I never found in the embraces of my sweetheart then or in long inebriated conversations with my fraternity. Pages were filled with words, reading, which made me proud. They were mine! But the euphoria was short-lived. About 50 pages later, the entire exercise book and the photocopy of the book I was translating turned into pulp as the heavy downpour slashed the already broken window and drenched my study-cum-bed.

Throwing the pulp away was actually surrendering myself to destiny. I resigned from the job I was engaged in and found myself to be a well-sought-after full-time private tutor of English. For a decade next, I had no time for myself, as the world of films radically transformed from analogue to digital. A decade later, almost at midnight while I was waiting alone at the bus stop far away, I suddenly found myself confronting myself. I discovered that although my hair had turned grey, I was exactly at the same point where I had been a decade and a half back.

And the middle: It was the time I burnt the midnight oil to change the course of my life. I started writing scripts and looked around for potential film producers.

Reciprocation from them came in the form of empty promises. As I carried on the drudgery, one evening in 2015, I noticed two familiar pictures on my Facebook wall. It was posted by Arun Khopkar, who was only known to me as the maker of Figures of Thought (1990), a revealing documentary film on the paintings of Bhupen Kakkar, Nalini Malani and Vivan Sundaram. (Though I had watched Mani Kaul’s Ashad Ka Ek Din (1971), years ago, the main actor had never registered in my mind).

There were few comments as weird as one could expect on social media. Something prompted me, and I too commented that while the known one was the last frame of Satyajit Ray’s Apur Sansar (1959), the other one was that of the author Bibhutibhusan Bandyopadhyay and his son Taradas Bandyopadhyay. In no time I received an inbox message from the author.

Let me take this opportunity to quote Arun Khopkar here to present his point of view from an excerpt of Changing Perspective, his introduction to the Bengali translation of his book: “One day, while reading Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay, I found a picture of him, carrying his son on his shoulders. I felt a déja vue. I thought and thought and sure enough, it was a spitting image of Apu carrying his son Kajol on the shoulders, in Satyajit Ray’s Apur Sansar. I was sure that Ray must have done this intentionally. When I held the two pictures side by side, I was overcome by a strong emotion about this great literary tradition, consciously being recreated in cinema. I posted both pictures on Facebook. I identified the Ray photograph and asked the readers to identify the other. Within minutes, I got a reply giving its precise source in the collected works of Bibhutibhushan. The sender was Satyabrata Ghosh, the translator of the present book. Ghosh had read the Hindi translation of my Guru Dutt book and loved it. He asked for my permission to translate it into Bangla. We exchanged emails*. He sent me the translation of a couple of chapters. I was surprised by the sensitivity of the translation, albeit with my limited knowledge of Bangla. He conveyed the mood of its literary style and rendered the technical parts of the text with precision. Years passed by. Ghosh was looking for a suitable publisher and also coping with making his own living. One day I got a call from him. Lo and behold! He was speaking from the office of Bhasha Sansad. I am grateful to the publisher for readily agreeing to bring out the present edition. Till today Ghosh and I have never met, either in real or in cyberspace! Only the minds had been in dialogue. I sincerely hope that we meet soon”.

So, up close, I am finally happy to get away from the Barthesque-Deridian-Fukoist lexiconic domain, which still exists as words and phrases without context. Instead of matching myself with the footnote hunters, I now am a part of an indigenous text that Aun Khopkar had penned. It not only elucidates the complexities of Guru Dutt’s work, but also provided me with a way to approach films that matter to me in days to come. Now, even at the risk of sounding absurd, I was listening and writing words that Arun Khopkar had uttered in his book.

*The source book for Bangla translation – Nishikanth Thakar’s Guru Dutt: Teen Ankiya Trasdi arrived to me by a courier from Arun Khopkar within a few days of our interaction...

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)