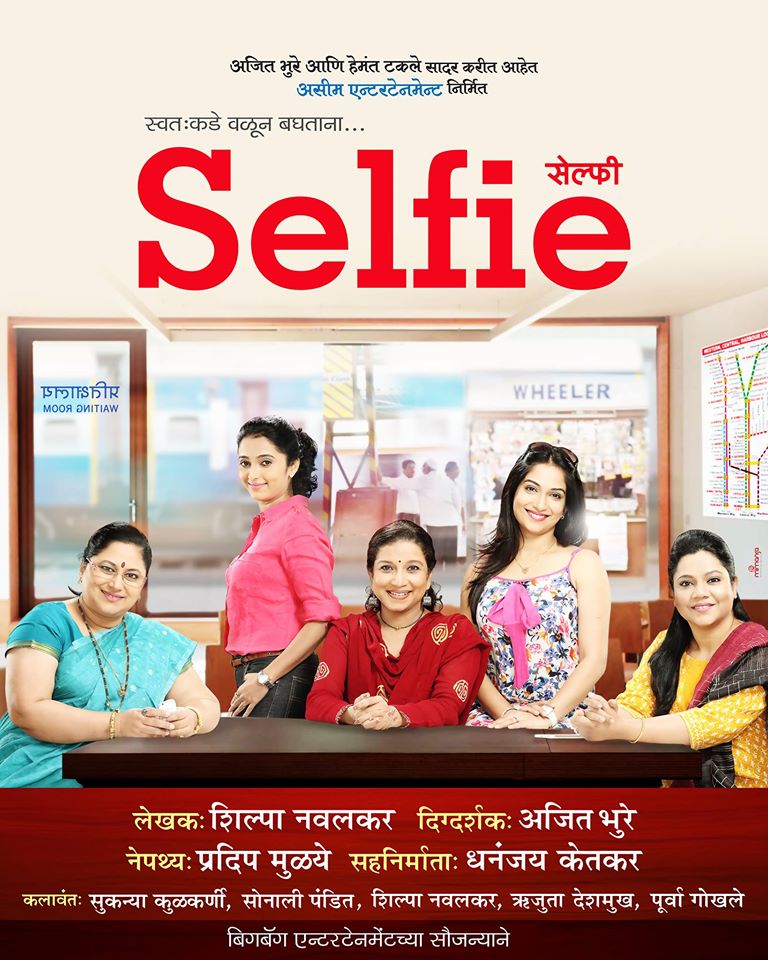

Female bonding is rare in Bollywood movies, so a play about strangers meeting in a railway waiting room on a stormy night has been doing well in multiple languages. Selfie (by Shilpa Nawalkar) in Marathi, Hindi and English, and The Waiting Rooms (by Prayag Dave) in Gujarati.

The Gujarati production, directed by Dhiraj Palshetkar went on to become a hit, despite its offbeat subject. Bhamini Gandhi leads the cast as the garulous Reva, hiding a painful secret. The play is set in the waiting room of a small railway station in Garhwal, with rain lashing outside and the train delayed due to landslide.

Four women of varying age and class strata are marooned in that drab room, with phone signals down, and no other more of transport out of the area.

Reva is the simple, sari-clad Gujarati housewife, who came to Garhwal alone, because her husband was caught up at work. She is the nosy chatterbox, and has the typical Indian way of asking awkward questions, with no notion of privacy. The soft-spoken, salwar-kameez clad local teacher Suman is the least fazed because she knows of the vagaries of the weather in the region. How she understands Gujarati is explained later.

Radhika is a career woman with an impatient, condescending manner—dressed in western clothes, she smokes and at some point in the play pulls out a bottle of vodka from her bag. In a very authoritative way she also gets up and slaps the fourth in the room—a rude teenager Kruttika, who won’t listen to reason. She is dressed in the teen fashion—western casuals, rucksack, boots—and has an attitude to match.

Once the differences between the four women-- their backgrounds discernable from their costumes and speech—are established, the play goes into the territory that would be familiar to travelers, especially women, who find themselves in a similar situation. When people are amidst strangers, they tend to open up a lot more than they would with people they know; with strangers they are not likely to meet again, there is no fear of judgment or exposure. People easily confide in fellow travelers, sometimes unburden their secrets, secure in the knowledge that they won’t cause any disruption in their normal lives. Then, if they run into someone as frankly curious and open, like Reva, who asks probing questions without a qualm, long-held defences can easily be breached.

The query about how Suman understands Gujarati gets as an answer the revelation that she used to have a Gujarati boyfriend. The other three are shocked to learn that the man abandoned her—left promising to return to marry her, and never did. The address he gave her was fake, and she had no means to contact him in pre-cell phone days. Worse, she remained unmarried and still waits for him twenty years later, because she loves him.

If that story is tragic, then Kruttika tells of how she was dumped in an orphanage by her father; when she grew up, she traced him, but he refused to accept her. The strong and confident Radhika has a sad back story too; she was betrayed by her husband, who took revenge for the divorce by kidnapping her daughter.

The unsophisticated and cheerful Reva, with no expectations from her marriage or bitterness about her husband’s feudal attitude towards her, also has deep wounds that are uncovered later.

Gujaratis would identify with an indulgent laugh, the woman who travels with copious amounts of food in her bag—when she opens it, theplas, half a dozen kinds of pickles, and several packets of snacks are laid out on the table. She is generous enough to share with the other three. (“This is no time to eat theplas,” protests Suman. “There is no fixed time to eat theplas,” says Reva breezily.)

Eventually, over her horrified protests about what is right and wrong for women, Reva has a couple of pegs of vodka that Radhika contributes to the impromptu party and the women break into a rambunctious dance—all the stress built up over the evening evaporates in that unbridled seizing of the moment. They can dance with abandon, because nobody—or rather no man—is watching. And nobody is around to disapprove.

The women are seen outside of the traditional roles they are forced into by society and free to express themselves, both their joy and their angst, in a kind of spontaneous sisterhood, which is what is so appealing about the play.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)