KALEIDOSCOPE: HUMRA QURASHI’S BOOK IS A WAKE UP CALL

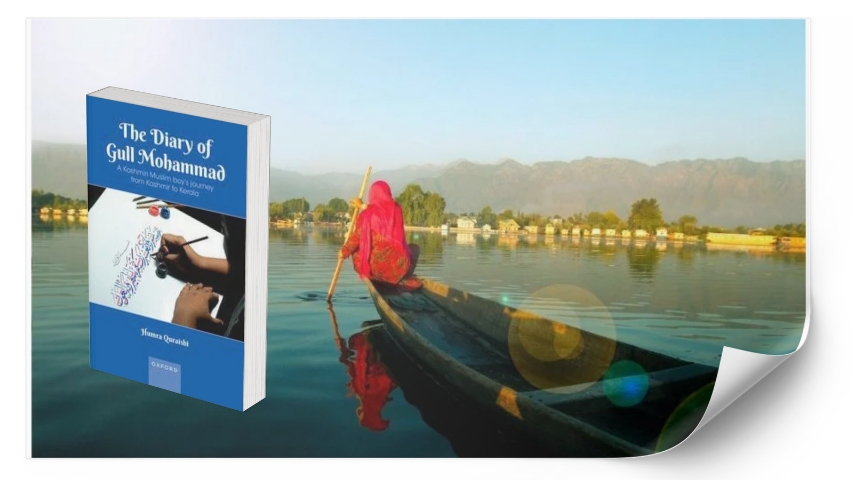

by Vinta Nanda January 20 2024, 12:00 am Estimated Reading Time: 9 mins, 41 secsHumra Quraishi’s book, The Diary of Gull Mohammad - A Kashmiri Muslim boy’s journey from Kashmir to Kerala, is an eyeopener. Once in it, it is unputdownable. It’s about the lives of Kashmiri Muslim children wasting inside and outside Kashmir, writes Vinta Nanda.

Humra Quraishi is a Delhi based writer, columnist and journalist who had been reporting from the Kashmir valley for a long time. She’s been writing extensively on the situation there and focusing on its inhabitants. When I asked her why telling stories from Kashmir is important, she said, “I have been reporting on the situation in Kashmir for years and been a witness to the grim situation and the blatant human rights violations taking place there…brutal tragedies inflicted on the inhabitants of the valley”. As a writer and journalist, she tells me, it is her duty to document the truth.

I am also curious to know why she has written The Diary of Gull Mohammad - A Kashmiri Muslim boy’s journey from Kashmir to Kerala. She informs me that right from 1990 onwards she has met and interacted with scores of Kashmiri children and teenagers. Adding to that she says, “I have seen for myself the anxieties and apprehensions they go through. It’s a tough existence for them. I decided to write this young Kashmiri teenager Gull Mohammad‘s diary so that we get to know what they are going through. It is such a painful situation when even the youngest is not spared”.

Gul Mohammad left Kashmir and the story is about his journey outside the valley. How difficult was it for him, I ask Humra. “The painful situation only compounds for the Kashmiris when they step out of Kashmir, and go to other cities and towns of the country in search of a livelihood. The bitter reality is that Kashmiri Muslims find the going tough because they are viewed with suspicion. Communal propaganda precedes them wherever they go, especially the young students from the madrasas. And, in this surcharged atmosphere, slurs are hurled upon them, they are taunted by the political mafia roaming around everywhere”.

She also tells me that earlier in the 1990s, the Kashmiris residing in the valley could at least express their anger through the administration, which is run from New Delhi. “It’s unfortunate that today there’s an ominous silence that hangs in the air everywhere you go in Kashmir. The residents are fearful of speaking out, they worry of the consequences”, she says.

It's a poisonous air in Kashmir, with Kashmiri Muslims being marginalised in their own hometowns. “These are challenging times especially for the young. The youth born during the 1990s are the worst affected – they have only seen violence, curfews, crackdowns and searches taking place in their homes and neighbourhoods, which has terrorised and frightened them. They feel they are under siege”.

I’m reproducing an extract, a searing piece, from Humra Quraishi’s book, The Diary of Gull Mohammad - A Kashmiri Muslim boy’s journey from Kashmir to Kerala.

Extract: As I sit and begin to write this Introduction to the diary of a 14-year-old Kashmiri boy, Gull Mohammad - who, because of the prevailing ground realities in the Kashmir Valley is shifted by his parents from their home

in Srinagar’s downtown to a madrasa in New Delhi and then confronted with further twists and turns in his life – faces of hundreds of innocent children do stand out.

For the last three decades and more, I have been visiting orphanages and madrasas in the towns and cities I travel to. Even while residing in New Delhi, and later in the suburbs/NCR, I have been visiting madrasas rather too regularly. With that, interacting with the children - the so-called madrasa children - and also with the maulvis, though, it’s only occasionally that I could meet the children’s parents or grandparents.

Many of these children are orphans or semi-orphans (one of the parents was dead), but even those whose parents are alive seem to be living cut off, because their parents are in no position, financially, to keep travelling to meet them. I got the impression that a large number of these children have been sent to madrasas so that they get two square meals a day and perhaps have a ‘safe’ roof over their heads.

These visits to the madrasas got me close to the realities in which these children are surviving. Not to overlook a vital factor, as a majority

of these madrasas do not have televisions sets nor radios, nor any of the modern-day connecting gadgets, so the traditional living conditions are intact and with that the innocence of these madrasa children. Their stark innocence, raw emotions, that forlorn look in their eyes has left an imprint. It is difficult to describe that look of helplessness in their eyes and body language, and together with that my own dilemma of how to reach out to them. After all, my visits to these madrasas have been somewhat brief.

Though each time I’m tempted to stay back longer but as a woman

I have to adhere to the supposed don’ts! Traditionally, single and unescorted women walking into boys’ madrasas is not the ‘done thing’. It is not accepted, nor expected! And if women do go ahead and walk into the confines of a boys’ madrasa with rations or food, they are not expected to linger around for long.

During my visits, I sat talking to the children and the maulvis about their daily routine; what they ate, what they read, and also about their families and ancestral setups back home. I could manage to grasp backgrounders to them. Most of the children came across as shy and subdued and didn’t talk much, but their eyes carried varying emotions…relayed much. A large number of them lacked confidence to such an extent that they couldn’t talk beyond a word or a sentence or two. Needless to add, their body language relayed nervousness and anxiety.

My madrasa visits have been emotionally fulfilling for me. I developed

a bonding and connect with these children. So much so, that if I wasn’t a writer (i.e., surviving as a full-time writer!), I would have been only too happy and relaxed manning a madrasa and looking after the madrasa children! Yes, that would have been the case, because by now I have seen too much of the worldly people and am left totally disillusioned by the layers that surround them. I’m completely put off by the fake and synthetic settings to the so-called who’s who of today’s India.

In contrast stand out the ground realities of the madrasas and the innocence of the children housed there. Of course, the conditions of the madrasas and also of the Muslim orphanages differ from region to region. Several children’s ‘homes’ situated in the Kashmir valley (where orphaned and even semi-orphaned children are lodged), are comparatively better than most of the madrasas I have visited in and around New Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, and in Haryana’s Mewat belt. In these madrasas, it’s just the sheer basics to the daily survival that stood out.

It came as a pleasant surprise to see many of the Kashmir Valley-situated orphanages follow a ‘via media’ between a madrasa and the regular mainstream education - in the sense, the children attend a regular school but in the evenings and early mornings (i.e., after attending school and before setting off for school ), they read the Quran and tend to other religious texts.

This, according to me, is the best possible combination, but for obvious reasons not quite affordable. Not to overlook is the fact that unlike in the Mughal era or even in later decades when the Zamindari system was not demolished and abolished, madrasa teaching was funded and taken care

of by this ruling class; today, the madrasas are maintained on meagre resources, mainly put together by the community members or at times by the waqf boards. In fact, today the children brought to the madrasas by their relatives are from the economically deprived and socially disadvantaged families. As I have earlier mentioned, it wouldn’t be amiss to say that many of these children could have been sent to the madrasas for the very basics -food and safe shelter.

Interestingly, until the 1970s, or perhaps even until 1980s, the middle class did enrol their children for madrasa education and did so with great pride and confidence. Many professionals I have come across, told me that for their early education, they attended the madrasas in their towns or cities and qasbahs. One of my former colleagues at the Academy of Third World Studies (Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, where I was a visiting professor), Dr Nasir Raza Khan, told me that until class eight, he had studied in his home town-situated madrasa, Niazia Nizamia, in Bihar. With English not as the medium of instruction in madrasas, how did he cope with further studies, and also what about those talks that fundamentalism holds sway in madrasas?

‘Yes, English was not taught…and till class eight I didn’t know many of the elementary English words, but that didn’t make me feel disadvantaged. Later I picked up the English language; it required a lot of hard work but I managed.

Today Muslims are going through tough times because of the “thappa” (blot) thrown at them by vested interests, that Islam is radical, but those are all false stories only to defame the community’.

And I was rather surprised to hear the New Delhi-based lawyer, M.R. Shamshad, tell me that he and his siblings did their schooling in a madrasa in Bihar. Today, he comes across as though he had a public school background to him. Also, much against the popular perception that only Muslim families send their children to study in a madrasa, the fact is that this wasn’t always the case. In the traditional setups, when communal poisoning was not unleashed to divide and distance, even non-Muslim families sent their children to madrasas for education. In fact, several years back, in 2006, I had come across this feature in the Outlook magazine, and I found it so very laden with off-beat facts that I kept it safely with me all these years.

This feature by Jaideep Mazumdar could be an eye-opener for madrasa-bashers. He wrote, ‘The Bengal Alifate - going to the madrasa here is like studying in any other school. Proof: Some 40,000 Hindus, 12% of total students, study in them. They are co-educational - in fact girls out-number boys and sit in the same classroom as them. No mullahs teach here, there are several Hindus among the teachers. Save for a compulsory paper in either Arabic or Islamic Studies, the syllabi is the same as in any other secondary school of the state. The class X certificate is recognized by the state secondary board. They (madrasas) are popular with Hindus as the fee is minimal, the teacher student ratio is 42:1, and the quality of education is often better…’

The Diary of Gull Mohammad (2023) by Humra Quraishi. Published by Oxford University Press India.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)