-853X543.jpg)

KAMLESH PANDEY: Ballia to Bollywood via Ishtihaarpur

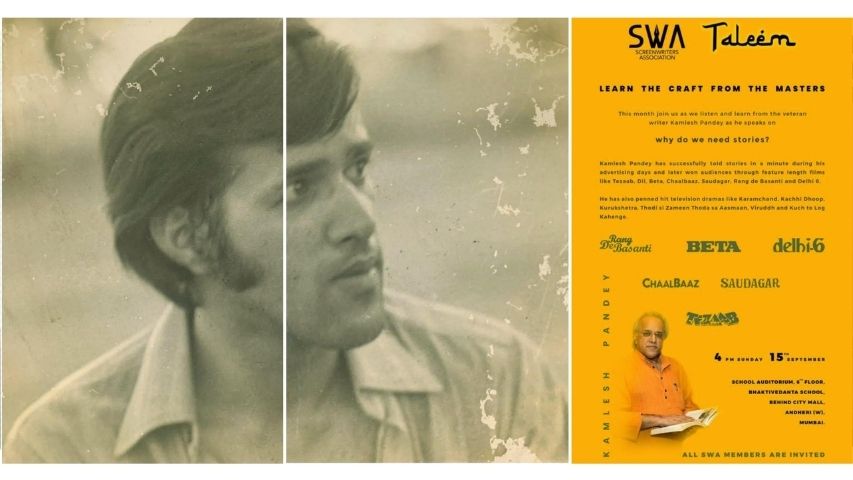

by Aparajita Krishna February 16 2022, 12:00 am Estimated Reading Time: 33 mins, 35 secsAparajita Krishna goes with adman, writer Kamlesh Pandey on a long walk through his life and career, bringing back beautiful memories from the well travelled road.

On a particular date I emailed my questions to Kamlesh Pandeyji with an apology that the length of the questions may read long, but that is because the information about him gathered by me could be misleading in parts and misinformed as well. And hello! The very next day I had a perfect set of answers mailed back. Soon after came a rejoinder with a revised version saying, 'On a casual reading I noticed two typos, which had escaped my attention (I am 74!), so I could not let them remain in my draft.’

The bluff about Bollywood writer’s fetish for procrastination, dilly-dallying, carelessness got called off. Wordsmith Kamleshji further WhatsApp’d, ‘I have been in advertising long enough where everything is wanted yesterday.’

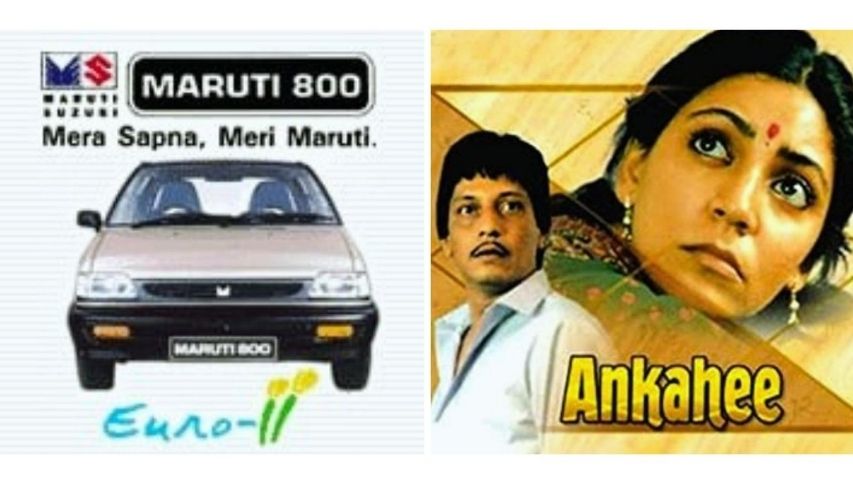

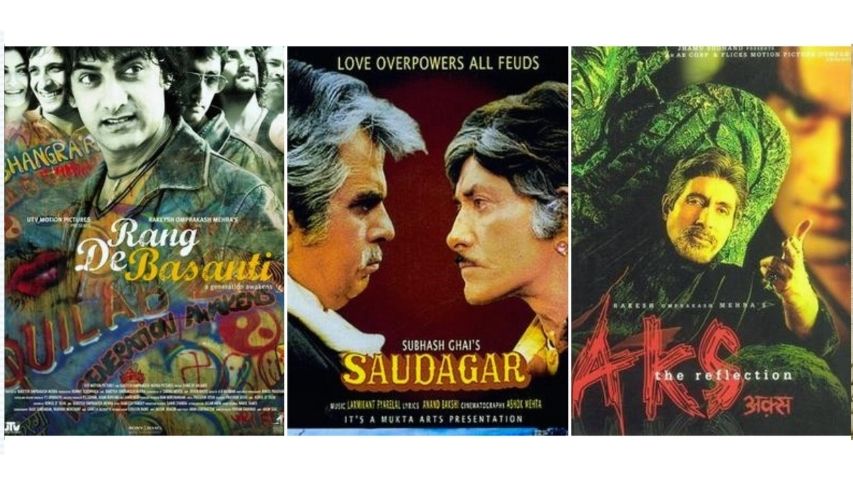

India’s Hindi cinema has a heterogenous identity. In that one language cinema rests many types of Indias, her people and cultures. Mainstream Hindi films typify many genres and imaginations; from the realistic to the bizarre. Kamleshji has in his powerful repertoire of film-work travelled from the more delicate Ankahee and Thoda Sa Romani Ho Jayen to the sharp-edged Tezaab, to the hyper-dramatic Saudagar, to the unusual-to-outlandish Khalnayak, to the new-age path-making Rang De Basanti and Delhi 6. Add to that his pioneering work in Indian advertising for which in 2021, Rediffusion appointed its alumnus as ‘legend in residence’. Further add to that his television repertoire, from good old Doordarshan days to the present Satellite content. And, he is still a work in progress.

Amid a bundle of stories, a crowd of characters, a rush of life flooding the mind, a writer has to constantly delve in the silence of his own unspoken words to write his story. Kamleshji has herein spoken the personal and the professional with deep honesty and the confidence that his experience gave him. This talk, strung with anecdotes, is a chapter on Indian advertising, Indian films and Indian television.

Can you recall the first or the first few films you may have seen in your hometown Ballia in Uttar Pradesh? Your childhood memory.

I come from a remote village in Ballia so no theatres and hence no movies. The first movie I ever saw was in 1956 when I visited my Tauji in Jabalpur. The movie was ‘Insaniyat’ starring Dilip Kumar, Dev Anand and Bina Rai. I wondered why everybody was going gaga over the actor who played Mangal (Dilip Kumar) and cried at his death scene? Because I found the Chimpanzee Zippi who played the comic partner of comedian Agha a much better performer. I shared this incident with Dilip Saab while working on ‘Saudagar’ and his reaction was ‘So I lost to a Chimpanzee?’

Do give us a little summary of your familial background before you touched Bombay’s shores.

I come from a farming family. One night the Ganges took away everything -our home, cattle, farms. My father and uncles had to leave home and take up jobs in cities to survive.

I was good for nothing; neither good in mathematics nor in science. And to make it worse, I suffered from severe speech impediment. Besides, I was the eldest son in a joint family. Not only had I to carry the burden of setting myself as an example in studies, but also be seen as an ideal elder brother for my siblings to follow. Not exactly a happy childhood. I was always under pressure to perform and be a good boy, getting teased by kids and neighbours. So, I avoided playmates and became a loner. Books were my only friend whenever I could get any. The only two things I was somewhat good at were Hindi as a language and drawing. I actually wanted to be a painter. Since some of my uncles were in the defense forces, I too was forced by the family to try for NDA and failed miserably. I really had no future and my family had no hopes for me. They worried how I was going to survive. Somebody suggested to my father to get me admitted into Sir J.J. Institute of Applied Arts, Mumbai (then Bombay) which trained students to become visualizers in advertising. I could at least earn enough to survive.

You did get admission into Sir J.J. Institute of Applied Arts Bombay in 1965. Were you at some point expelled from there for asking ‘uncomfortable questions’?

The curriculum was 50 years behind the times. I used to argue with my teachers that advertising had gone beyond lettering. It was now a business of creative ideas and I was not going to be a signboard painter, which required that particular skill. I would often be ordered to leave the class, which actually proved to be a blessing in disguise - I would end up at USIS, American Center and British Council libraries, and for some strange reason, read books on cinema besides advertising.

The new wave or parallel cinema was just emerging. For Godard, Antonioni, Fellini and Bergman in Europe, we had Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, Mrinal Sen, Basu Chatterjee etc. My world suddenly took flight! I never got a chance to go to FTII (except as a visiting faculty a couple of times) but subconsciously my education in cinema had begun. I used to write notes on toilet paper borrowed from these libraries because I never carried paper with me. The rejection by my teachers at J.J. became so frequent that I dropped out after three years from the four-year Diploma course.

For the next four years I tried to survive in the usual way strugglers survive in Mumbai - starvation, frustration, hopelessness, loneliness. In fact, for a brief shining moment I even toyed with the idea of suicide, but a German documentary rescued me - for the first time a tiny film camera was inserted into a woman and the entire journey from conception to birth was recorded. Watching the documentary, I wept, and understood for the first time how much life invests in each of us and a suicide is the most ungrateful way to pay back to life.

Curiously, Sir J.J. Institute of Applied Arts, which could not tolerate my questions for three years, started inviting me to talk to its students and a few times even as a Chief Guest at their annual exhibitions once I became the most awarded copywriter in advertising in 1970’s and 80’s! And I paid them back by telling the students that ‘Dropping out of J.J. is better than staying in J.J. because you have to succeed not because of J.J. but in spite of J.J.! I am your proof!’ I was further compensated when in 2006 I received advertising’s most coveted award, ‘The CAG Hall of Fame’ at J.J., from the institute that could not suffer me when I was there.

You would utilize your time by reading in the libraries. You wanted to write and direct and so when you learnt of a vacancy going in 1970 at Hindustan Thompson Advertising Agency you applied. There is a story to it.

Yes, my usual quota of books per week was around 6 books, two from each of the three libraries. I never wanted to write for films or direct, but reading improved my English, a boy educated in vernacular from the backwaters of Ballia. That was also the time when I first found what a script looked like. I borrowed Pauline Kael‘s book ‘Raising Kane’ from USIS, an in-depth analysis of the classic ‘Citizen Kane’, which also had the screenplay of the film.

After four years of struggle, around 1970, one fine day out of sheer frustration I wrote that legendary job application, ‘I need a haircut, and if you can give me a job, I can get a haircut’ to the Creative Director of Hindustan Thompson. I had written the same job application to a few more Indian advertising agencies, but expectedly they must have thrown them into their waste paper basket or wiped their asses with it because they were all Indians. Fortunately for me, the Creative Director of Hindustan Thompson happened to be an Australian, Murray Bail. He not only regretted that he did not have a vacancy right then, but asked me to contact him after three months. To say that I was shocked would be an understatement - the Creative Director of India’s No.#1 advertising agency was asking a good for nothing boy to contact him after three months for a job! What else can one call a miracle? I still wonder what he saw in me.

After three months I promptly contacted him. He called me and gave me a copy test, an ad for ACC cement for a Shakespeare play souvenir. Could I find anything common between Shakespeare and cement? I did. With my headline, ‘If Shakespeare had been a bricklayer, his works would have still survived time because he knew the secret - concrete base’. I also drew the visual of Shakespeare laying bricks - each brick one of his plays. Murray’s comment? ‘Kamlesh, your spelling is bad and your grammar sucks, but one day you are going to be the best copywriter in this country.’ Then came the next legendary joke.

He asked me what do I expect as a salary. My colleagues from J.J. who had passed their Diploma were getting anything between Rs.75/- to 150/- a month. I kept quiet. Murray offered Rs.500/- a month! I kept quiet because his Australian accent sounded more like Rs.50/- a month. I thought I deserved it because I was not even a diploma holder. I kept quiet (mainly because my spoken English was worse than my written English - that earned me the title ‘country bumpkin’ at Hindustan Thompson). ‘Silence is golden’ came true when Murray blurted out, ‘Kamlesh I can’t do better than Rs.800/- a month right now!.’ The rest is history.

I proved Murray right by winning the Best Copywriter of the Year Award for four years in succession since it was instituted in 1978. Today, Murray is one of the most admired, honored and celebrated novelists in Australia. The first opportunity to prove Murray right came my way in 1972 when Nusli Wadia of Bombay Dyeing rejected 49 campaigns done by other senior copywriters. My then Creative Director Andre Cyson asked me, the junior most copywriter, to try something.

I wrote my first cinema commercial about three goons who enter a Bombay Dyeing basement shop to rob the safe, but get distracted by the goodies on display while the dynamite they had lit into the safe burns. The safe blasts open with only a title card inside - ‘Steal The Show In Bombay Dyeing’.

Nusli Wadia loved my script, Zafar Hai shot his first cinema commercial and Andre gifted me my first copy of a Hollywood screenplay ‘Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’, which I still have. Years later in 2000 when Rakesh Omprakash Mehra was in London casting British actors for ‘Rang De Basanti’, his Casting Director, a British girl, took my script home. Her father saw my name on the script and exclaimed, ‘I know this guy, I had gifted him ‘Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’! Yes, my story had come full circle.

You started your advertising career in Bombay in 1970 with HTA as a copywriter and followed up with other agencies. You worked on many noteworthy campaigns, revolutionized the scene and won the Best Copywriter of the Year Award for 4 consecutive years. Do share some of your favourite campaigns: print and film.

I had done some decent work at Hindustan Thompson but Sista’s and Grant did not suit my temperament, though at Grant I had been promoted to Associate Creative Director. Osho entered my life in 1964. By 1973 when I left Grant, I had started meditating, taken Sanyas and became his disciple. One fine day, I saw an ad done by Rediffusion and told myself this is the kind of ad I would love to do. Rediffusion, then hardly a year old and a 5-client agency, gave me, the Associate Creative Director of the fourth largest agency in India, a copy test! I loved their confidence. They agreed to take me on, but at a salary lower than what I was getting at Grant.

I was perhaps the first adman who changed jobs for a lower salary. I could afford it because I was single and had no expensive habits. At Rediffusion, me as Copy Chief and Arun Kale as the Art Director, started rewriting the Bible of creativity in Indian advertising and began to win hundreds of awards. Some of the lines that come to my mind were, ‘How young did your God die?’, ‘Do mistresses make major corporate decisions?’, ‘The curious poverty of highly paid executives in India’ and ‘Is marriage a one-stop solution to lust, laundry and loneliness?’ for Caliber Suitings.

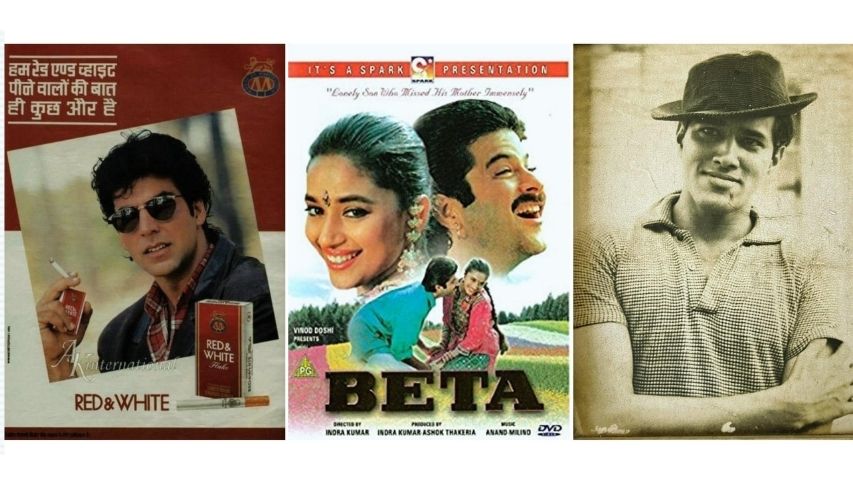

Some of the copy lines have now acquired iconic status: ‘Whenever you see colour, think of us’ (Jenson & Nicholson), ‘Hum Red & White peenewalon ki baat hi kuchh aur hai’ (Red & White cigarettes), ‘When it can’t be done, it must be done’ (J&N Corporate), ‘Is it bad to look good’ (Lakme), ‘Mera Sapna Meri Maruti’ (Maruti 800).

I was not only the first bilingual copywriter who started with original copywriting in Hindi, but also the first to start writing original television commercials when other agencies used to simply translate their English originals into Hindi at the rate of 50 Paise per word and edit their 60-second cinema commercials into 30 seconds for television.

Some of the most awarded films were for Garden Vareli, Jenson & Nicolson, Bush Transistors, Lakme, etc. My Jenson & Nicolson TV commercials, which ended up being almost episodic sitcom series, made a star out of Dalip Tahil. Many ad-filmmakers like Prahlad Kakkar, John Mathew Matthan and Mahesh Mathai got their first films from me. Being himself an art director in advertising, Satyajit Ray was a frequent admirer of good advertising, including mine. So, when I saw his ‘Seemabaddha’, which had an ad-film for a fan, I thought of getting him to do one for my client Khatau Saris.

Satyajit Ray shared a hobby of collecting ancient books with one of our Calcutta executives so I dared to send a script through him. Surprisingly, Satyajit Ray was not offended. After one month he got back to me and told me that my 60-second script had 12 shots whereas his single shot was not going to be less than 3 minutes, so how could he do it? In response, I sent him a 60-second Nescafe ad-film done by my friend Prahlad Kakkar, which had 60 shots! He laughed and said he can’t think that fast!

Your generation nurtured our advertising, marketing ground in a native way. How does today compare to yesterday? Since globalization was not even a word in our lexicon, nor the advantage of global media, so you must have originated rooted campaigns and not just the copy from foreign shores.

We were so fearless that our clients used to feel intimidated. Unwittingly we had built such a reputation for ourselves that if a client did not like a Rediffusion ad, he did not have the ability to judge good creative. And it worked so well that when there was no Account Executive to take my work to the client for his approval, I used to get my peon to do that and he had the 100% hit rate for selling my campaigns! Today things have changed for the better in one respect - some Indian advertising and professionals are getting international recognition and awards. In my time, we could not afford to enter international advertising competitions - they required payment in Dollars and those days a maximum of only 100 Dollars were permitted as foreign exchange by the Government of India. But unlike today, in my time, we had the freedom to take advertising to its creative precipice, and sometimes, even take a leap.

An excerpt of your talk in the Vijay Tendulkar Memorial Lecture at the 17th Pune International Film Festival 2022, as mentioned in Hindustan Times, Feb 8 2022 says, “I used to hang around during the rehearsals of Ghashiram Kotwal where playwright Vijay Tendulkar himself would be showing actor Mohan Agashe the minute details of how Nana Fadanavis would behave. Tendulkar was always searching for the truth, which is hidden in our psyche as wounds and he would rip off our bandages to expose us to that truth through his writing. When I tackle risky subjects I remember Tendulkar and get inspired to write the truth.” So I ask, who were the writers who influenced you in your formative years from among the literary and film-writers?

From Hindi, fiction writers like Mohan Rakesh, Kamleshwar, Rajendra Yadav, Phanishwar Nath Renu, Raj Kamal Chaudhary. From Marathi, P.L.Deshpande, Mahesh Elkunchwar, Tendulkar. From films, Wajahat Mirza, Ali Raza, Kamal Amrohi, Pt. Mukhram Sharma, Arjun Dev Rashk, Nabendu Ghosh, Abrar Alvi, Rahi Masoom Raza, Gulzar, to name just a few. I would have loved to include Salim-Javed but their work has been mostly derivative - if there had been no ‘Gunga Jumna’ and ‘Mother India’, there would not have been ‘Deewar’.

Who were the film directors whose works shaped your aesthetics?

Francis Ford Coppola, Oliver Stone, Spielberg from Hollywood. Satyajit Ray, Tapan Sinha, Hrishikesh Mukerjee, Mehboob Khan, V.Shantaram, Guru Dutt, Raj Kapoor, Bimal Roy, K.Asif, Vijay Anand, N.Chandra, Pankuj Parasher, Subhash Ghai, Amol Palekar from Indian cinema. They all contributed to my growth as a screenwriter.

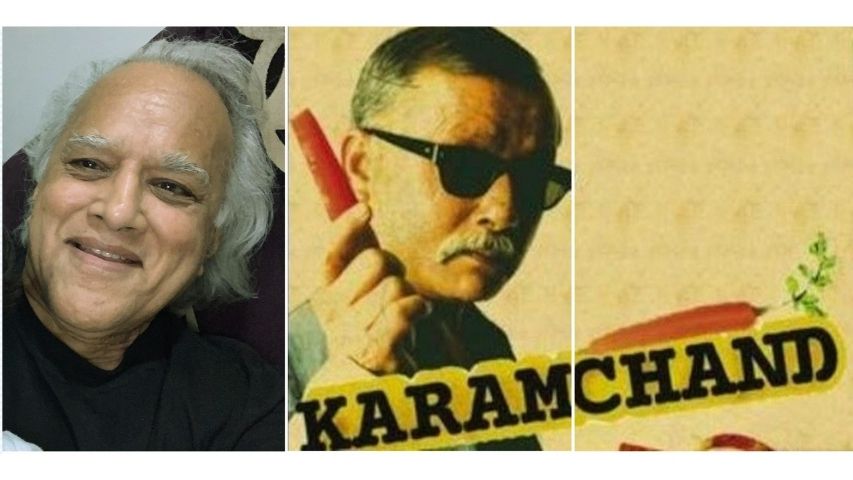

While still in advertising you got offered to write for our comparatively nascent television. Back in the 1980s did you write the cult comic-thriller Karamchand (1985) for DD or helped facilitate it? There is confusion in the credit titles.

‘Karamchand’ was written in a chaos. For a 9AM shift next day, there wouldn’t be a script in hand. So Pankuj Parasher and Pankaj Kapoor would land at my house at around 9PM. We would eat and drink and discuss what should be the clue for the next day’s murder. They would leave past 12AM and I would sit down and write till 6AM. At 6.30AM, Pankuj’s assistant Sanjay Gupta would call me about the artistes required and we would be shooting promptly at 9AM! About credits I never bothered because I was having a successful and comfortably settled life writing for advertising, winning hundreds of awards and never taking writing for television and films seriously.

I never even thought that I should have fought for my credit. That’s why I was often cheated out of well-deserved credit. Not only for ‘Karamchand’ but even for ‘Thodasa Roomani Ho Jayen’ (in which you had acted), I was credited with only ‘Hindi Lyrics and Dialogue’. Amol refused to change. Same thing happened in ‘Rang De Basanti’ when my credit for the screenplay and dialogue was denied to me even though it was in my contract. But if I had made a case for it, ‘Rang De Basanti’ would have suffered because of the prolonged court case.

Ankahee, a very sensitive film, came in 1985. It had your screenplay and direction by Amol Palekar. It was based on Kalay Tasmai Namaha by C T Khanolkar. It starred Amol, Deepti Naval, Dr Shreeram Lagoo. How do you look back on it? Was that your first film writing?

I had known Amol from his theatre days because advertising professionals were the biggest audience for plays in Hindi, Marathi and English. We were friends, that’s how I got to write ‘Ankahee’. Before ‘Ankahee’ I had written an original screenplay ‘Bayaan’ for a small-time underworld don who used to fund Marathi movies. Somebody told him about me and he asked me to write a traditional family drama, which I hated. He wined and dined me and took me around to meet people like Haji Mastan, Kareem Lala, Samad Khan and other assorted hitmen, smugglers and owners of bars and gambling joints. So, my ‘Bayaan’ was perhaps the first underworld script in Indian cinema.

Manya Surve, was a daredevil real outlaw who had been shot recently in an encounter near Wadala. N.Chandra was brought on board as the director, but the producer could not afford his price so the project fell through and remains unproduced. ‘Ankahee’, which got me the best compliment from none other than Javed Akhtar after he saw the film (Javed to Amol: Apne dost ko bolna mere pet par laat mut maare), almost made me Amol’s house writer. So, whatever Amol made, I was writing it. I was still learning on the job and yet Amol kept repeating me project after project and I am grateful to him for his faith in my writing.

I changed the original play a bit and made the heroine an astronomer working at the Nehru Planetarium who looks at the stars in the sky as a scientist. This made the film a debate between science and superstition because Dr.Lagoo played an astrologer who predicts that his son Amol’s first wife will die in childbirth. So, Amol is married to a mentally challenged Dipti Naval. However, it is his girlfriend who commits suicide and Dipti Naval survives in childbirth. Thus, the prediction of the father is proven wrong. But a distributor who believed in astrology interpreted the ending as a prediction coming right because Amol’s first love dies anyway.

Kamlesh Pandey’s work on television set standards. His collaboration with Amol Palekar and Chitra Palekar in particular I was very fortunate to be privy to. They worked together in serial ‘Kachchi Dhoop’ (1987) and ‘Naqab’ (1987-1988). ‘Kachchi Dhoop’ was beautifully adapted as a serial from the novel ‘Little Women’ by Louisa May Alcott. It marks the acting debut of Bhagyashree Patwardhan and of Ashutosh Gowariker. ‘Naqab’ featured Anil Chatterjee.

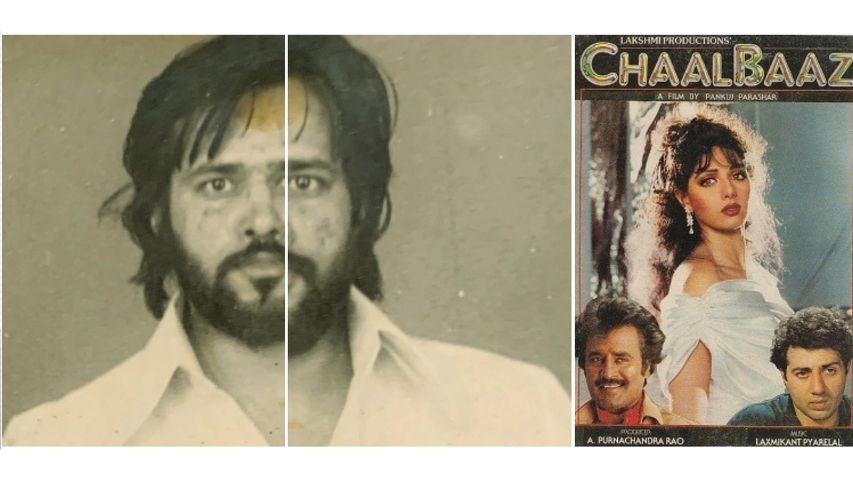

Then came your string of mainstream commercial hit films. Jalwa (1987-dialogue), Tezaab (1988-script), Chaalbaaz (1989-dialogues-screenplay) and Dil (1990-dialogue).

I wrote ‘Jalwa’ for Gul Anand just as a lark, but it became a hit and I unwittingly got the stamp of being a hit writer (the gossip about me used to be that ‘taksaal se ek naya sikka aaya hai’). I had met N.Chandra for ‘Bayaan’, which had fallen through. He used to stay close to my office in Worli. One afternoon he just dropped in and narrated the story of ‘Tezaab’ and asked if I would like to write it. I was impressed by the story and told him that ‘Tezaab’ could be ‘Awara’ of the 1990’s. ‘Why?’ he was surprised. I told him if Raj Kapoor had been alive in 1987 and wanted to make ‘Awara’, he would have made ‘Tezaab’. That is why there are many scenes in ‘Tezaab’, which are a tribute to ‘Awara’ - Munna’s introduction, Munna and Mohini’s love-hate scene.

N.Chandra, according to me, could have been the next Mehboob Khan. He had the potential, but somewhere down the line, he lost the fire. ‘Tezaab’ was hated in trial shows because many people could not understand its complex screenplay (there was a flashback within a flashback), but we refused to make it easier for the audience. Even my friend Shekhar Kapur felt the film was too demanding and gave ‘Tezaab’ not more than 8 weeks (that too because of the song ‘Ek Do Teen’). It went on to celebrate golden jubilee and 100 weeks in many theatres. ‘Dil’, ‘Beta’, ‘Chaalbaaz’, ‘Anari’, ‘Saudagar’ and ‘Khalnayak’ followed, Filmfare and Screen awards followed, and something, which I never expected happened - I was stamped with ‘hit writer most in demand’. In Bollywood, even a dog from a hit film is stamped ‘hit dog most in demand’, I was at least a writer.

The 1990 telefilm ‘Thodasa Roomani Ho Jayen’ (produced by good old Doordarshan) is my all-time favourite. It was brilliantly written in verse form - musical. Amol Palekar was the producer-director with concept-screenplay-dialogues by Chitra Palekar, Hindi dialogues-lyrics by you. Was it inspired by the English play ‘The Rainmaker’ by N Richard Nash? To me it is also reminiscent of Vijay Tendulkar’s wonderful breezy play ‘Panchi Aise Aate Hain’. The film came during the times when this kind of artistic cinema was handicapped by a lack of thrust in release avenues. ‘Thodasa Roomani Ho Jayen’ would have been a landmark film in today’s satellite, digital age. It is one of the most creatively daring experiments in Hindi cinema. The film stars Anita Kanwar’s is an exquisitely nuanced performance. Music was by Bhaskar Chandavarkar. Do tell us about the writing.

‘Thoda Sa Roomani Ho Jayen’ was funded by Doordarshan as a television film produced for the princely sum of Rs.20-25 Lakhs, to be telecast on Doordarshan, not screened in theatres. Since we did not have the obligation of the box office, we decided to have some fun. I told Amol that since it was a musical, I would like to write it in the form of ‘Nautanki’ in which straight dialogue seamlessly flows into lyrical, poetic dialogue and lyrical dialogue seamlessly flows into a proper song. Since I was also writing the songs, I would write a scene and if I felt that this scene needed poetic dialogue or a song, I would first write the poetic dialogue or song and then move further.

The film had Naseeruddin Shah to play the role but he backed out. ‘Tridev’ had become a blockbuster so Naseer refused to do a small Doordarshan film like ‘Thoda Sa Roomani Ho Jayen’. We tried Rishi Kapoor, but he also refused. I tried Anil Kapoor, but he had become a big star after ‘Tezaab’ and ‘Beta’.

‘Thoda Sa Roomani Ho Jayen’ was released in theatres and ran for a month. Years later, while having a haircut in a saloon, suddenly on the radio my name was announced and one of the songs from ‘Thoda Sa Roomani Ho Jayen’ started playing. The barber was as surprised as I was. Actually, I had begun my film career as a lyricist as far back as 1973 when Poo Sayani, an ad-film maker, had asked me to write the lyrics for her film ‘Hungama Bombay Style’ that she was making for the Children’s Film Society. The film starred Amrish Puri, Naseer and Pearl Padamsee. The title song was sung by Manna Dey.

The 1990s saw a string of mainstream hits. Notably ‘Saudagar’ (1991-dialogue, ‘Narsimha’ (1991-dialogue), Beta (1992-dialogue), Khalnayak (1993-dialogue). Do share some notes.

Subhash Ghai had seen my ‘Jalwa’ and had asked Pankuj Pararsher as to who was his writer. Pankuj told him my name. Subhash Ghai told Pankuj that now I was his writer. Subhash Ghai first called me for his ‘Deva’. But ‘Deva’ fell through for some reason. He wanted me to go with him to Bangalore for three months to write ‘Ram Lakhan’. I politely refused. Not only did I have a day job at Rediffusion, I was busy writing ‘Dil’, ‘Beta’ and ‘Rakhwala’. But I promised that I would find time for him when he calls me for his next film. And he did for ‘Saudagar’. He put me in a difficult situation because Dilip Kumar and Raaj Kumar were the only two actors I have ever been a fan of (I had written an article for The Daily Eye when Dilip Saab passed away).

Under Subhash Ghai I learned how not to be a fan when you are the writer of the film. I bonded with Raaj Kumar extremely well because both of us were huge fans of Russian novelist Dostoevsky and the Upanishads.

‘Narsimha’ was even better than ‘Tezaab’ but it was released at the wrong time. ‘Narsimha’ had some communal violence and post Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination the audience had turned off from any kind of violence. Javed Akhtar had been signed to write ‘Beta’ but he considered it too regressive and refused. Indra Kumar whose ‘Dil’ I was already writing, asked me to take on ‘Beta’ because he already had dates from his stars. I took permission from Javed Saab as was the industry tradition and accepted. I have no aversion to writing family dramas because the family is an Indian reality whether we like it or not. I have grown up in a joint family and have experienced first-hand the trials and tribulations, laughter and tears, politics and manipulations that go on in a family.

‘Khalnayak’ I loved because it was the ‘Ramayana’ from Ravan’s point of view. ‘Mujhe Jeene Do’ was perhaps the only dacoit film where the dacoit hero had no hard luck story to justify his acts, but it was an exception because most Indian mainstream films about anti-heroes had a hard luck story to justify their crimes. I suggested to Subhash Ji that our Khalnayak should be unapologetic like a snake who is made that way by nature. But he persuaded me that we cannot take a risk. Thus, in my view, ‘Khalnayak’ was diluted to some extent for the sake of the box office. But Subhash Ghai has been the director I have learnt most from about storytelling for cinema.

The new decade saw you continuing to give popular films: Aks (2001), Rang De Basanti (2006), Yuvvraj (2008) and Delhi 6 (2009). Jazbaa (2015) appears to be your last film work. Any reason why the momentum of work decreased? Obviously you must have chosen to do less films. Rang De Basanti still resonates. On the 10th anniversary release of the film Aamir Khan presented you with the first copy of the book of the script signed ‘Thank you Kamlesh Ji for giving us such a lovely script.’

I had written an original screenplay titled ‘Samjhauta Express’, which was going to be the debut film for Abhishek Bachchan. But J.P.Dutta came with ‘Refugee’ and after his film ‘Border’, he was a more bankable director than Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra - for whom ‘Samjhauta Express’ was meant to be Abhishek’s debut film. So ‘Samjhauta Express’ was shelved and joined the heap of many of my unproduced scripts. As a consolation, I was offered ‘Aks’, which was basically an idea developed between Amitabh Bachchan and Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra. I thought the story belonged more on Sony TV as an episode of ‘Aahat’ instead of being the vehicle for the return of an actor of Amitabh Bachchan’s stature and caliber to the big screen after his long absence. I could understand Amitabh Bachchan’s keen interest. He was getting to play the hero and villain both in one film and no actor having even one-tenth of Amitabh Bachchan’s talent would have refused such a role. I agreed because I could sense something philosophical in it - that good and evil are not opposites, they need each other, they complement each other, they are reflections of each other. I gave the villain Raghavan a line from the Bhagavad Geeta, (‘Na koi martaa hai na koi maartaa hai, main to nimitt maatr hoon isliye bura mut maananaa’). But nobody, not even the so-called literate film journalists, noticed my rather mischievous attempt to use the Bhagavad Geeta to justify killing.

I have spoken a lot about ‘Rang De Basanti’ in the media so let me skip it. ‘Delhi-6’ was a simple comedy of ‘My Big Fat Greek Wedding’ flavour, but was somehow turned into a philosophy-heavy film rewritten by some other writers during production when I was busy with the writing ‘Bhairavi’ for Rakeysh. ‘Yuvraaj’ was more out of friendship with Subhash Ji. I have written quite a few forgettable films simply as an obligation or a promise to fulfill. ‘Jazbaa’ because Sanjay Gupta used to be an assistant to Pankuj Parasher during ‘Jalwa’ and ‘Karamchand’, and I had promised him that I would write for him when he became a full-fledged director himself.

You returned to television when you headed Zee TV from 1991 - 1995. One reads that in your tenure at Zee Antakshari got made (one of the best formats we in India developed as native program). Then you introduced Tara which became a milestone serial. Then came Campus, Banegi Apni Baat, Philips Top Ten, Zee Horror Show, Mere Ghar Aana Zindagi and Filmi Chakkar. It must have been a rewarding tenure. Any nostalgia?

I have always believed that television is a more powerful medium than cinema because it is addictive and repetitive. Like water and air it is available at the flick of a button. I had written ‘Kachchi Dhoop’ and ‘Naqaab’ for Amol and ‘Karamchand’ for Pankuj. So, when I got a call from Zee to be its Programming Head, I took it as my prayers were answered. My friend Alyque Padamsee (God of advertising) advised me against my decision. He wondered why I am taking this risk when I was successfully riding two tigers like advertising and films? My friend Shekhar Kapur advised me against it, telling me that Zee TV would not last more than three months because who could buy an expensive satellite dish antennae (Rs.25,000/- that time) when Doordarshan was available free to air? But I had to romance the hot new girl next door, satellite television.

During my tenure from 1992 to 1995, Zee TV became perhaps the fastest growing television network in history. Fan-mails used to be brought to the office in trucks from the Worli post office. Initially we kept records, but finally the volume got so big that it was sent to be recycled into making cardboard boxes at Essel Packaging. I was commissioning shows almost on a daily basis. Raman Kumar and Vinta Nanda came with ‘Tara’, Deeya Singh and Tony Singh did ‘Banegi Apni Baat’, I gave Amitabh Bhattacharya ‘Campus’ and even started the Zee Horror show every Friday against all sane advice. I mined radio for shows like ‘Antakshari’, ‘Philips Top Ten’, many games shows, and packaged them as a product with my experience in advertising. At one time, 9 Zee shows were in the top 10, Ramanand Sagar’s ‘Krishna’ being the only non-Zee show in ratings.

In around 2007 you worked on the serial Thodi Si Zameen Thoda Sa Aasmaan and Virrudh. In 2011 aired you wrote Kuch Toh Log Kahenge on Sony. In this you collaborated with Haseena Moin by adapting her very popular Pakistani serial-Dhoop Kinare.

Post ‘Rang De Basanti’ I had taken a sabbatical when Ekta called me to head the writing department for her show ‘Kahani Ghar Ghar Ki’. I accepted because I was free and I was the one who had commissioned her first show ‘Hum Paanch’ on Zee TV before I quit. At Balaji, Ekta and Smriti Irani joined hands as producers and called me to write ‘Thodi Si Zameen Thoda Sa Aaasman’ based on my story. After I left Balaji, Smriti Irani became an independent producer and asked me to write ‘Viruddh’ for Sony, which was her idea based on a real character. After ‘Viruddh’, Sony got the rights to adapt Haseena Moin’s classic television serial ‘Dhoop Kinaare’, but Haseenaji demanded that I should be the writer. In a video call she claimed that she was my fan whereas I had been her fan all through my writing career and had learned how to write for television only by watching her iconic shows like ‘Dhoop Kinare’ and ‘Tanhaiyan’. Surprisingly, while Pakistani films were often pathetic copies of Indian Hindi films, they seemed to have mastered the art and craft of writing for television.

That brings me to ask what makes the Pakistani television writing so good while ours over time fell from a very good start-up to abysmal low? The audience does not give tuition to the channels before their commissioning, so TRP is a myth, as in the audience chooses from what is served to them. Do you agree that our Doordarshan 1 and DD2 library of programs of yore is still the best? Zee start-up was also very good. What ails our television in 2022? It is severely diseased. But of course monetarily it is a very rich medium. Has money destroyed it?

Curiously, the Golden Age of Indian television came and went on the most unlikely platform - Doordarshan. Television, especially satellite television in India, has been mostly funding waste. ‘Gobar mein ghee sukhana’ as they say in Bhojpuri. The only positive I see is that it has given jobs and a comfortable life to writers, many of whom have now become producers. I am glad OTT seems to offer a tough competition to satellite television, which may in the long run improve our satellite television.

You have also been a visiting faculty teacher at Subhash Ghai’s Whistling Woods.

I was, but for a very short period. I found the passion lacking. Cinema needs passion more than anything else like facilities, faculty and equipment. Most of our legendary film directors never went to a film school.

At the Screen Writers’ Association (SWA) you along with your senior colleagues helmed the movement to bring about the new amended Copyright Act allowing royalty rights to the writer irrespective of change of ownership of film and audio-visual content. SWA promoted script workshops for young writers. Is the level-playing field now fair?

Yes, we fought for an amendment in the Copyright Act for our rights to royalty, which we won in June 2012 when it was passed by both houses of the Parliament without a single vote against it. It is perhaps the most unique right to royalty because it is inalienable and remains with the family of the writer even 60 years after his death. We have more or less won our battle for our due credits, but we are still fighting for our Minimum Basic Contract. SWA often offers screenwriting workshops, legal aid, monthly pension to senior ailing writers and sometimes even arranges pitching sessions with producers. The level-playing field is still not there, but we are working towards it.

Do tell us about your present creative work in progress.

Besides Rediffusion, a couple of scripts, one is waiting for casting, the other two are works in progress.

Kamlesh Pandey continues to be a creative man - of yesterday, today and tomorrow.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)