In an age when there is so little thought given to the past, a new Marathi play makes a case for preserving memories.

Soyare Sakal is the fifty-seventh production by Bhadrakali Productions, the group established by the late Macchindra Kambli, over three decades ago, with a Malwani play Chakarmani. After his death in 2007, his wife Kavita Macchindra Kambli and son Navnath picked up the reins of the group, and have been producing Marathi plays in various genres from mainstream to offbeat - like the recent, two-woman musical Sangeet Davbabhali, that has been winning awards and acclaim.

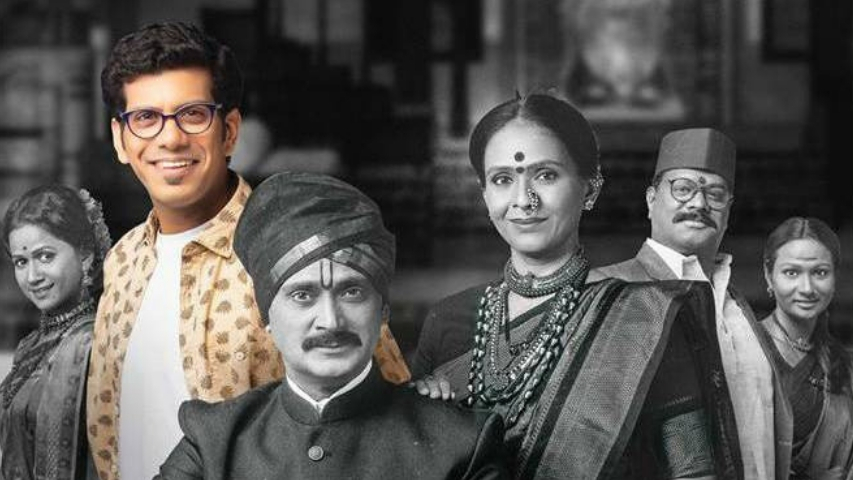

Marathi play Sayare Sakal

Written by Dr Sameer Kulkarni and directed by Aditya Ingale, Soyare Sakal starts with US-based Shaunak (Ashutosh Gokhale), who is visiting his 76-year-old aunt Sindhu in a Maharashtra town, to help her form a trust for the family-owned temple. Shaunak’s father left for the US as a young man and never returned, because of bitter memories of the past.

In America, he has adopted the attitude of discarding anything that is of no use, but in India, Sindhu has preserved objects of sentimental value to her, and believes that memories are what make up human existence. While rummaging through his aunt’s endless possessions with the idea of helping her get rid of junk before he goes back to the US, Shaunak finds an old trunk with gramophone records, drama scripts, an idol of Krishna, and a book of devotional writings by his grandfather.

He is curious about the significance of the objects, and his aunt tells him the family history that his father never referred to. Half the set (by Pradeep Mulye—excellent) is Sindhu’s home, and other half turns into a rural mansion, where Shaunak’s grandparents lived (Avinash and Aishwarya Narkar). The flashback covers an uncle who had left home to join the stage (the trunk belonged to him) at a time when it was considered disreputable, Shaunak’s father as an eight-year-old traumatized by having to light the uncle’s funeral pyre, and the family’s displacement during the anti-Brahmin riots that followed Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination, the support offered to them by a courtesan.

The family’s past affected the present in unexpected ways, decisions taken by a father had long-lasting repercussions on a son’s life. By the end of the story of ups and downs, Shaunak realizes why his aunt cannot let go of memories, “because nobody is a stranger, we are all connected.”

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)