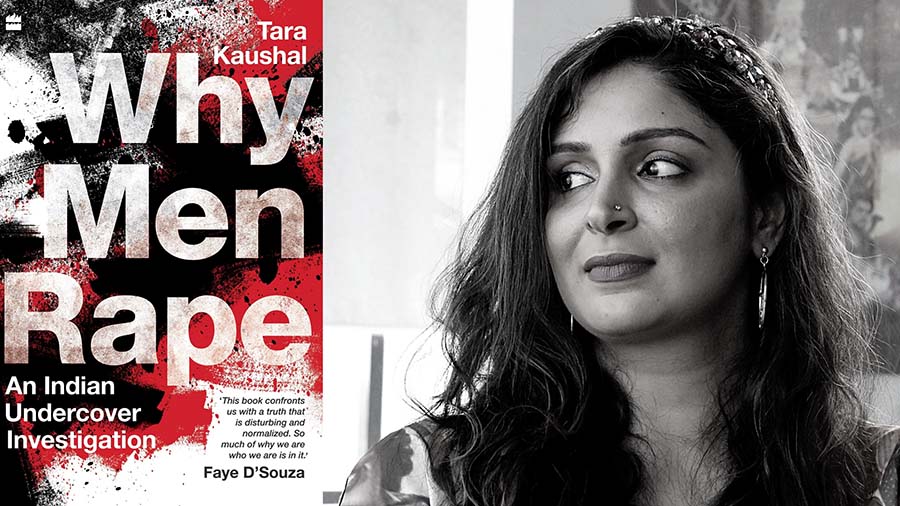

Tara Kaushal: Why Men Rape

by Vinta Nanda June 20 2020, 5:59 pm Estimated Reading Time: 12 mins, 8 secsVinta Nanda interviews author Tara Kaushal, on the eve of the release of her book Why Men Rape: An Indian Undercover Investigation.

I know Tara Kaushal by a recent friendship.

We were meant to meet a couple of years ago but we didn’t. When I was making a documentary film last year - it is yet to be completed and released – I sought her out. This time when I met her in person, I was completely impressed because it is rare to see a woman so driven, so determined and then so blasé about being that way.

I interviewed her for my film and in that I noticed how deep she had delved in the subject that she was writing her book about. Moreover, what she told me in the interview about her process was unbelievable. But what she has done as well as what she has gone through to do so is real.

So real that it cannot be imagined.

Here I talk to her about the journey she took, to come to this moment in which she is about to release her book.

When did the thought strike you that you should write the book and also do talk to us about that moment in which you started writing it?

This book, Why Men Rape: An Indian Undercover Investigation is one part of a project called Why Men Rape. While this project has been the culmination of a long professional and personal journey of at least 25 years, the idea for it came to me in 2013, after the Delhi Gang Rape. That’s when I started reading, planning and saving for it—eventually taking it on full-time four years later, in April 2017.

For me, getting molested daily on the DTC buses that would take me from Noida to college in Chanakyapuri severely impacted my attendance - though I loved my course and topped throughout, and though I carried a knife. So, while the country empathised with Jyoti Singh Pandey, Jyoti Singh Pandey could have been me from ten years before. And this is why I was so deeply shaken in the aftermath of that incident - it was so close to home.

I wish, however, that I could pinpoint the exact moment the idea came to me, but I simply don’t remember it! I just know that my first notes date back to 2013.

How did you go about selecting the subjects for your book?

When I had set about searching for subjects, the first avenue I pursued was finding their identities through their survivors. I received most responses from the call I put out on Facebook, where my audience is mostly as privileged as I am. Then there were all the friends who had told me their stories over the years; and also, strangers who sought me out, unsolicited, at parties, online, even at a tile shop (!), upon hearing about this project. I spoke to seventy women who have been raped. (At that point, many more since.) Now, since gender violence usually follows class lines (a theory I unpack in the book), I had the names of seventy-two elite men who have raped.

But, as much as I didn’t want to only promote the Shakti Kapoor idea of rapists - ‘the Other’ men lurking in bushes waiting for a savarna virgin to come along - these elite men weren’t representative of India either. For me, finding rapists in the Shakti Kapoor mould was the far more challenging task.

To find men from other social classes who had raped, I knocked on every door I could - from NGOs to the police to local contacts to detective agencies to local media. Eventually, I found subjects across social classes and locations across the country.

Tell us about the first interview you did and what it was like for you on the personal front after that?

My first interview was in September 2017, with one of these elite men who had raped a journalist. These elite men are represented in my book in a section titled ‘Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing’ - and that’s exactly what I found him to be. Murky themes lurked beneath the veneer of respectability.

I was shaken after interviewing this man, and since - dealing with rage and depression until a complete meltdown nine months after I started the project. In December, after five subjects, I’d hit rock bottom, unable to sleep, having blackouts, lashing out. Fortunately, I took a break from research and went abroad to write for a few months.

I resumed the undercover research in July 2018. It coincided with major loss and grief on the personal front, so I was semi-functional for a while. I was glad to be done in December!

It’s hard to immerse yourself in this kind of violence and come out unscathed. Having said that, it’s not like I’ve emerged jaded, believing all men are capable of or nurse the desire to rape. I wouldn’t have been able to do and survive this without the love of my extra-special spouse, Sahil, and of friends and family, many of whom are male.

What was the process like in the beginning and how did it change as things went along?

I have been writing about gender, sexuality and sociocultural issues for fifteen years. Almost as soon as I decided that this was the project I was going to be doing/book I was going to be writing, I realised it would be expensive - not only would I not be earning for the duration of the book, the research would cost me too. Between 2013 and 17, while Sahil and I oriented our finances and life towards this goal, I decided to read exclusively about gender violence.

Since I actually started working this project and book full-time in 2017, it has seen different stages, as all projects do. There was the crowd-funding - far harder and more time consuming than I had imagined. Then came the subject interviews - everything about this was hard, from creating the questionnaire to finding the men, and, of course, actually meeting them. I took a five-month break to write and collate the information I had, and to conduct my expert interviews. Then I resumed the undercover research.

A year-or-so of writing followed, pretty-much the whole of 2019, and then I was finally done early this year.

Talk about the most difficult phases and about the easiest, to us?

Although I found the research phase extremely emotionally and physically hard, I would have to say the hardest part of the process was definitely the writing. I don’t know about fiction writing, but non-fiction or at least my book exists in a space between order and chaos, method and madness. I had to take all the data - the studies, the books, and the theories - and see how they intersected with my subjects’ narratives. Many days, I’d wake up just willing this damn book to be over, made doubly despondent by the knowledge that it would only be over if I got to work and finished it! I lost myself in my book.

And, the easiest part - That would have to be presenting this work to the world. Many writers struggle with finding publishers and making their projects see the light of day. Aside from the struggle to produce this work –crowd funding and everything else I’ve described - once it was on its way, it was easy. HarperCollins picked it up fairly early on, and now talks are on for the documentary!

Why are you as a person invested in the subject?

At the age of four or five I was raped by our gardener, a man called Mani, in the Naval colony in Cochin, despite my parents’ wokeness and vigilance. (I don’t remember the details, just his khaki uniform and penis, and blood on my blue dress.) Since, there was a lot of sexual violence in my life - I didn’t realise just how much, how much I had forgotten over the years, until I was going through my old writing to write the conclusion of Why Men Rape. But since my parents didn’t know about these incidents, I didn’t see them as having a direct impact on my life. (On my psyche, well, that’s another matter).

But when I was twelve, we moved to as civilians to Noida and, fuck, how starkly different it was! I was stalked, molested, flashed at and propositioned fairly regularly on my way to school. In light of the environment, my acting out and adolescence (when sociosexual norms kicked in, a universally unhappy time for kids, especially girls) - how my life changed! My well-intentioned parents curtailed my access to the outdoors, policed my clothing and hemlines, and imposed curfews. I was miserable. And maybe, just maybe, the questions I had started asking as a twelve-year-old baby feminist newly in Noida - why should the actions of men impact my life, the lives of women; why do they do it; why can’t they stop - sowed the seed for this book, published almost a quarter of a century later.

Tell us about your childhood and the time when you were in college? What was it that made you determined that you had to personally do something to address gender inequalities in India?

The details are not much different than what so many other children and women experience all over the world. And the aftermath of sexual violence… There are as many ways to process child sexual abuse and rape as there are survivors of CSA and rape. But, my point is, why? Why must people be so damaged by other people? Why do those who are damaged want to do that to others?

Being raped has far-reaching consequences. So does sexual terrorism - the threat and fear of sexual violence. Women spend an inordinate amount of time preoccupied with safety - within and outside their homes. On the whole, patriarchy and the fear of rape keep women of all strata away from fulfilling and adventurous lives, demanding careers, equality, and freedom.

I wanted to undertake this project and write this book for myself, and for women in India and in the world.

Can you share an experience or two from while you were writing this book?

One of the worst days I had during the research was in Jammu, in November 2017. I realised my subject there - well, not there, exactly, but in a village in the Kathua district that was yet to gain the infamy it would in the coming months - was laying a trap for me. It had been a stressful day that was made much worse by drunken men banging on my door at the cheap-but-not-so-cheerful hotel I was staying at that night.

What was interesting to me was how I was able to make a direct correlation between my experience in Jammu and what followed in a similar Delhi hotel shortly after. As I wrote on Facebook then:

“Next to mine is what seems like an empty room that the staff is using. Every night for the past five, they have been making a huge ruckus - coming and going, screaming, banging on the door while friends (drinking?) inside laugh and don't open, the works - and, yes, till this late hour and even later.

I've thought of telling them to quieten down at night and/or about telling the manager in the day. But, after what happened in Jammu, I fear the repercussions and can't/won't. So I wait, in silence.”

It is so obvious how the fear of violence silences us. These experiences just underscored the raison d'être of the project and book.

You had mentioned to me earlier that there were times when you broke down. What happened and how did you get around those times?

I can pinpoint several times in my life during which I have been depressed. Two of those times were during this project. It was bad in December 2017; in July 2018, I was in the depths of hell, crying on the floor for days on end, unable to get out of bed. There was personal grief and loss; plus, it was during this period that I interviewed the doctor who raped one of my closest friends and left her paraplegic at the age of 12, so that didn’t help.

I did not feel I needed to talk about what I was experiencing so didn’t want therapy… but I did want some antidepressants! Calling mine ‘situational depression’, a doctor friend dissuaded me, however, saying I’d be over it before the meds would even kick in - they take around three months, apparently. I was indeed okay within three months.

I would not have been able to do this project without the army of friends and family that stood behind me. I took so much from, leaned so much on the people around me. They helped me through the lows - love, massages, food, shoulders to cry on, punching bags, flowers, I got everything I needed. And I took it all. I hope to be able to repay the love and favours I have received.

Where are you going to go from here? What's next on your calendar?

As I envisioned it at the start and as it currently stands, Why Men Rape is a multimedia gender journalism and activism project that spans two books, a documentary and an active online presence. The documentary is in the works. The second book will take some time: I’m not ready to tackle it yet. In the meanwhile, I am co-authoring another book in the human rights and gender-justice space, also with HarperCollins.

I always imagined my life and career would be divided into before and after this book, and it certainly feels like that already, even before the launch. I am open to exploring all the things the universe sends my way…

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)