Khalid Mohamed reconstructs the Rajesh Khanna he knew.Indian cinema’s first acknowledged superstar 10th death anniversary falls this month on July 18.

If the youth of the 1970s, aped any actor, needless to jog your memory, it was Rajesh Khanna (1942-2012). From his guru kurtas and his boyish swag to his flamboyant hand movements during song sequences, he had gripped the nation with his romance-exuding personality, abundance of charisma and his frequent forays into unconventional films, Ittefaq, Red Rose and Aavishkar to cite just three instances, which spotlighted his gifts as an actor.

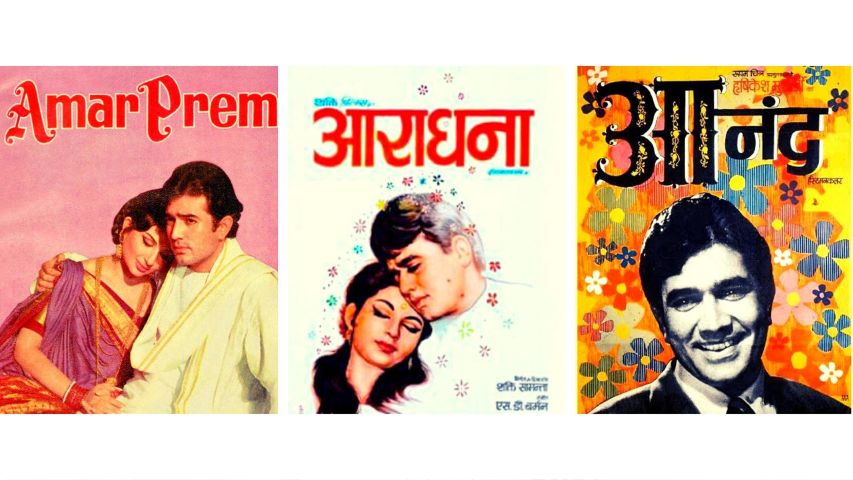

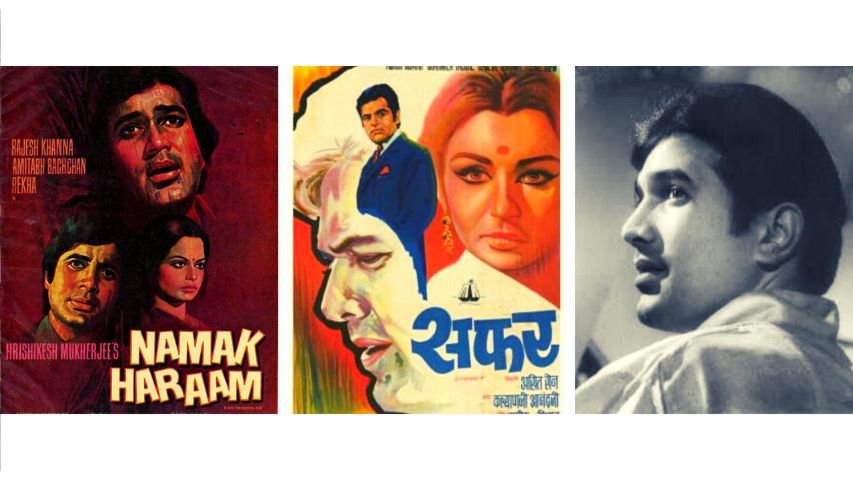

Of course, everyone has his or her personal favourites, mine being the tragic Anand, Khamoshi and Safar, the elegiac Amar Prem and the breezy Aradhana. The zingy fun flicks were Haathi Mere Saathi, Sacha Jhoota, Apna Desh and Train. I never tired of seeing them, admittedly a means to find an alter-ego of sorts in those growing-up-years-blues. One of his most quoted lines is, “O Pushpa, I hate tears,” (Amar Prem). And whenever he was buffeted by cruel circumstances on the screen, he had me weeping copiously in the dark of the auditorium, sharing his grief expressed through his melting eyes.

The first acknowledged Bollywood superstar, his 10th death anniversary is on July 18. And if you ask me, personally, no other star-actor has compared to him. Female fans were known to write him love letters in blood! Confession: I had even bought myself an unaffordable blue guru kurta (entirely unsuitable to my frame) from the upmarket tailoring shop, Shriman, close to the Gateway of India. Incidentally, it was designed by Baldev Pathak, the husband of Dina Pathak, parents to Supriya and Ratna Pathak. Baldev Pathak had avuncularly quizzed me, “Are you sure? Perhaps a Shashi Kapoor-style silk shirt would suit you better.” No go, I was hopelessly adamant.

On Rajesh Khanna’s passing away at the age of 69, there were reports vis-a-vis a section of his iconic bungalow, Aashirwad, which was purchased by him from ‘the jubilee star’ Rajendra Kumar who had moved to Pali Hill. Measuring 630 square metres, on the Bandra sea-front, the buzz was that it would be converted into a museum of his memorabilia.

In an interview to Bombay Times in 2009, about the museum, he had stated, “By the grace of the Almighty, my daughters Twinkle and Rinke are married, settled and have huge houses. They don’t need my property. But of course my daughters will take the final decision because it will be their inheritance.” Be that as it may, the museum didn’t materialise. It was bought by businessman Shashi Kiran Shetty at the quoted price of Rs. 90 crore.

Rajesh Khanna, nee Jatin Khanna, was born in Amritsar, and was adopted by Chunnilal and Leelawati Khanna, relatives of his biological parents. With his adoptive parents, he lived in the Saraswati building in Thakurdwar, a congested neighbourhood of Bombay. Whether this had any kind of psychological repercussions on the boy can never be accurately determined. He studied at St Sebastian’s Goan High School and then at Nowrosjee Wadia College in Pune followed by K.C.College in Bombay. Of the many stage plays he participated in school and college, Dharamvir Bharati’s Andha Yug seemed to stoke his appetite for film acting.

My friend Gulu Waney and I, lunatic Bollywood trackers, were aware that he’d been selected as one of the finalists at the Filmfare-United Producers’ Talent Contest. Ditto Manoj Kumar and Dharmendra, earlier. However, that contest win didn’t guarantee instant film contracts or stardom. Gulu and I didn’t know if he could afford it, but he’d roll up in a MG red sports car most evenings just below my friend’s third-floor apartment, to hang out at the pavement outside Churchgate’s Gaylord restaurant - the adda then of the film fraternity, especially of Shankar-Jaikshen and Raj Kapoor who would join them there occasionally.

Sure, Rajesh Khanna would make heads turn, but not of the moneybag producers, when he hung out on the pavement. Girls would hang out from the balconies in the adjoining buildings to chat with the wannabe actor, but the movie merchants would say under their breath, “Hurry or he’ll start pestering us again.”

Of medium-height at most (1,69 metres), ruddy complexioned, eyes, which crinkled at the hint of a smile, Rajesh Khanna aka Kaka possessed all the mandatory qualities associated with a Bollywood star back in the 1960s. He belonged to the north, as they used to say then, spoke Hindi fluently, threw attitude and the Churchgate college girls would swoon that from certain angles he looked like Alain Delon. Yet Shankar-Jaikishen wouldn’t ever think he was worth sharing a cup of the restaurant’s famous cinnamon coffee with. No matter. Khanna would smoke his 555 cigarettes right till the end of the butts. His body language, lolling on his car parked there, stated, “Hey guys, not to worry. My day will come.”

It did and how! In my waking memory I haven’t seen an actor who commanded the high hysterical fan following, which he did. ‘Rajesh Khanna worship’ was intense even if it did not have the sort of longevity that Bollywood’s first superstar should and could have commanded. The ‘super’ word hadn’t been coined before him, and Khanna’s tsunami-like popularity has not been surpassed ever. His appeal cut through generations, from the campus set to grand pops and grannies.

The Gaylord gadabout’s story was something of a Bollywood fantasy script. His first batch of films ranged from the whodunit Raaz (which also introduced Babita), Aakhri Khat (a black-and-white film in which the focus was more on a lost little boy), Aurat (a potboiler

from Chennai) and Baharon Ke Sapne (glam director Nasir Husain’s attempt to go realistic in vain).

Rajesh Khanna was a loser. Till Aradhana (1969) altered his life dramatically. Followed by a series of major hits, Do Raaste, Bandhan, Anand, Namak Haraam and Amar Prem. He could do no wrong. Even the unconventional Ittefaq, with a minimal number of characters, was a winner, leading to his long-time association with Yash Chopra. In fact, today’s reigning film production banner Yash Raj is believed to have been a combo of the names of the director’s and Yash Raj(esh); the company had started with the production of Daag with Khanna, Sharmila Tagore and Raakhee Gulzar.

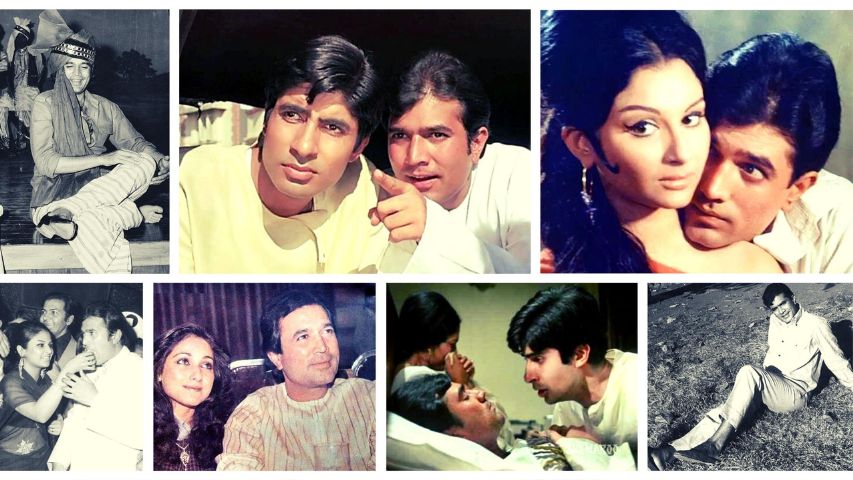

Preceding that, the first unquestionably “wow” performance was that of the eponymous Anand, the terminally ill young man (partially inspired by Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru). His death scene, with ‘Babu moshai’, Amitabh Bachchan, by his bedside is one of the most movingly written and acted scenes in Hindi cinema. Subsequently, It seems the two sparred with Hrishikesh Mukherjee over who should ‘die’ in Namak Haraam, a take on the Peter O’Toole-Richard Burton film Becket. Notwithstanding the controversy Rajesh Khanna got his death wish. After all he was a more powerful star then. Oddly enough, Rajesh Khanna excelled in death scenes, the other examples being in Anand, Safar and Khamoshi.

Nicknamed Kaka, his private life was endless grist for the gossip mills. Anju Mahendru, his long-time girlfriend, was suddenly out with his overnight marriage to Dimple Kapadia, still in her teens. The heart is capable of doing flip-flops but I do know he was besotted with Anju. At the outdoor shoot of Aan Milo Sajna in a hilltown, he would have to be cajoled by the assistant directors to end the hour-long phone calls he would make to her in Bombay. One of his co-stars told me, “I think he would often propose to her but she would convince him to concentrate on his career right then.” This story could be apocryphal but it is to Anju Mahendru’s lasting credit that she never went on record on being ditched as it were, when he married Dimple quite out of the blue.

With time and success, the actor, however, wasn’t making new friends, losing many of them it is said because of his mood swings and arrogance. Was it that facile though? Chances are that he could have been let down by his fair-weather friends. Chances are that he could have been hurt on being taken for granted. Shakti Samanta and he parted ways. Yash Chopra moved on to the next big super-actor freshly arrived on the scene, Amitabh Bachchan. Anger was in, romance was out. It is conjectured that Rajesh Khanna was offered Deewaar but disagreements with the two scriptwriters Salim-Javed proved to be a spoke in the wheel. It is tempting to think of how Kaka would have approached the characterisation of the vengeful Vijay Verma.

And to think once in Guddi, Dharmendra had said wistfully to Jaya Bhaduri who had acted as his obsessive fan, “Everyone wants Rajesh Khanna… So why me?” As it happened, the superstardom passed on to Guddi’s real-life husband Amitabh Bachchan who was just what Rajesh Khanna wasn’t: tall, swarthy, simmering rage brimming over and possessed a baritone voice.

As a rookie, I had met Rajesh Khanna on the sets of Dhanwan, when he was just about doing okay in showdom. A senior Filmfare reporter had told me about his mood swings, I wasn’t disappointed. Before I could ask the first question, he played a drum beat on the table between us. It could have been for two minutes but felt like 20. A year later I saw his other side: extra-affable and chatty. “As long as you don’t ask about my early days, I’m fine,” he grinned, ordering a virtual bakery of cakes to go with a cup of tea. That interview was conducted in the cavernous drawing room of Aashirward, in the presence of his then-girlfriend Tina Munim (they had just co-starred in Souten).

Tina, whom I knew ever since her debutante days in Des Pardes had changed perceptibly. For one, her usually pearly white teeth showed stains of gutka, a tin of which she was carrying right then. I couldn’t help balking, “Please throw that away!” To my surprise, she promised that she would. When the interview appeared, in which Rajesh Khanna for once had spoken out frankly, especially on the subject of his rivalry with Amitabh Bachchan, the actor sent flowers to me at the office with a note saying, “I’ve framed the interview and kept it on the bar where all my friends head anyway. PS: A million thanks for getting Tina rid of that gutka. We must meet again soon and next time, do stay for dinner.” That didn’t happen. Rajesh Khanna, I suspect, was essentially a closed person. He wasn’t likely to trust a journo beyond a point.

Which is why, maybe a year later, during another interface at his office between Khar-Santa Cruz, he wasn’t all there. But for a Man Friday, he was alone, the phone never rang once, all the lights hadn’t been switched on. He had turned monosyllabic and was in a tearing hurry to get the q and a ritual over with. His personal and professional lives were seriously floundering. Tina Munim and he had gone their separate ways. He was feigning to be upbeat but was clearly down in the dumps, avoiding questions, and seriously bingeing on Johnny Black. This was disturbing, indicating that when one’s success dims, so do his coterie and self-worth.

Whenever I asked Dimple Kapadia about him, she didn’t have a harsh word to say about their collapsed marriage. “He’s an incredibly nice guy,” she has said repeatedly. “I was just too young to get married. And maybe it was my fault that we couldn’t make it work.”

And let’s see, the last time I met Rajesh Khanna was as an MP, on a Mumbai-Delhi flight. We had a polite conversation. He said, “I hope you didn’t review one of my last films (Wafaa),” and laughed. “We must meet up but promise me we won’t go into those good or bad old days. Jo ho gaya so ho gaya.”

Whenever I pass by Aashirwad, there’s a note of consolation though. The new owner, I’m told, has commissioned a set of superb paintings by the eminent artist Atul Dodiya, on Rajesh Khanna’s films, as part of the interior décor of the bungalow. I’ve had a glimpse of them, they’re extraordinary.

So in a manner of speaking, the superstar still continues to live on in the beloved house that he built.

-853X543.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)