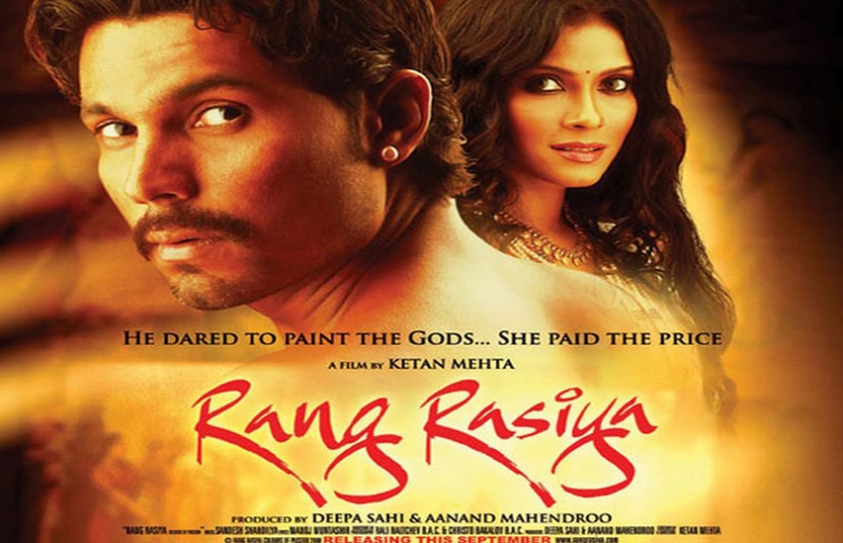

True Review: Rang Rasiya

by Niharika Puri November 7 2014, 8:05 pm Estimated Reading Time: 4 mins, 28 secsDirector: Ketan Mehta

Cast: Randeep Hooda, Nandana Sen

Rating: 1.5 stars

The makers clarify at the very outset that Rang Rasiya is a work of fiction based on Ranjit Desai’s Marathi novel. It is a relief, because nothing in the garish period drama will induce a shred of credibility for the legendary painter.

The film shifts gears from present day Mumbai where an auction of Raja Ravi Varma’s paintings is being disturbed by the puritanical custodians of culture, to Bombay, 1896 where the artist himself is on trial for the nudity in his paintings. Vikram Gokhale plays the lawyer, denouncing the paintings on behalf of Chintamani Patel (Darshan Jariwalla), head of the Dharma Rakshaa Samiti. Tom Alter is the British actor for all seasons, and here he plays an unbiased Justice Richards, who happens to be wonderfully fluent in Hindi.

Raja Ravi Varma chooses not to hire any lawyer for his cause.

“Aap kanoon ke baare mein kitna jaante hain?” asks the Judge.

“Utna hi jitna aap kalaa ke bare mein jaante hain,” retorts the prosecuted artisan, in what is possibly the only instance of decent dialogue in the film.

Cut to a childhood flashback in the 1850s of Ravi Varma’s budding talent. Cut to the courtroom scene. Cut to another flashback of his marriage. Here is where the exchanges between characters get pedestrian.

Ravi Varma offers to paint his newly wedded wife, who is appalled by the idea, to his dismay.

“Humaare parivar mein pati log aisa kaam nahi karte,” she says, coquettish.

“Toh kya kaam karte hain?” asks the glowering painter.

“Mazaa karte hain,” she smiles.

This is probably the only scene that depicts their marital life after the wedding. The blunt refusal has Ravi Varma painting a lower caste girl, their forced sensuality seeming more like a parody of erotica than the intended hedonism. A change in the political climate and a failed marriage forces him to move to Bombay with his brother Raja Varma. There he pursues Sugandha (Nandana Sen), who is to be his muse. The rest of the film chronicles his rise to fame, his foray into the printing press and the inevitable backlash that follows the anatomical depiction in his art.

For the best of its intentions and scale, Rang Rasiya eventually diminishes to being a poorly executed, inaccurately-customed, badly enacted test of patience. Each scene ends in either a great hurry or an abrupt fade-out, giving little time for it to linger in the audiences’ minds.

The costumes, though of earthy palettes, are synthetic with little attention to detail. Turbans are poorly tied or ready-made. Mr. Gokhale’s character of a lawyer wears a jabot (frilly) shirt, which lawyers never wore. The Maharaja of Baroda (Sameer Dharmadhikari) is shown to be wearing an English coat with Jodhpurs (breeches).

Ravi Varma’s home has the steady gleam of bulbs when electricity was to come to India much later in the 20th century. Mumbai’s iconic Watson Hotel stands tall as a historical relic and landmark. The one depicted in the film does not look like it at all.

The climax becomes a drag, culminating at the courtroom where the protagonist goes on a rant about India being the land of the Kamasutra, Khajuraho and great culture, where the spectators applaud, in the biggest cliché and ludicrous of all courtroom conducts.

In the film about an artist who celebrated the female form, little is done to flesh out the women who are no more than objects of beauty. We never know what becomes of Ravi Varma’s wife. There is no mention of the three children he had with her.

Feryna Wazheir features as Freny, a Parsi woman who is his admirer. There is no greater purpose given to the character other than blatantly endorsing ‘India’s leading daily newspaper’ and appearing in courtroom scenes to simper.

Sugandha may feature as a prominent character in the promotions but does not get a lot of screen time. We never know what excuses she must make to her family in order to meet the artist. Her family’s reaction as well as of the general public to her prominence in his art is revealed only in the end in a hurried scene. She, sadly, has little to do other than look demure or break into a teary-eyed run upon the slightest inducement.

The character of Dadasaheb Phalke, father of Indian cinema is reduced to an ingratiating extra in the background. Details of his friendship with Ravi Varma, and the painter gifting him his first camera are absent from the narrative.

One can understand the concerns of Indira Devi Kunjamma, his granddaughter, in trying to stall the fictionalised account of his life. It may be a dramatised portrait of his life, but it is certainly not a flattering one. Inserting the nugget of Ravi Varma being awarded the Kaisar-e-Hind, the highest civilian honour bestowed on an Indian citizen in the end titles does not salvage the film.

Rang Rasiya squanders away the potential to be a voluptuary historical fiction. The fact that it clashes with a bigger release this weekend does it no favours. But do yourself one and steer clear of this clash of colours.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)