The Political Debate: Morality vs Growth

by Sanjana Haribhakti October 22 2013, 3:24 pm Estimated Reading Time: 5 mins, 37 secsNever has Indian society been more bipolar than with its reaction towards Nerendra Modi. It is rare to find anyone that has a neutral opinion about him. His supporters project him as India’s messiah; the only man that can steer India back on course to achieve high GDP growth and someone who will overhaul our traditional system of governance plagued by inefficiency and corruption. His opponents on the other hand stop nothing short of demonizing him and making him out to be a Muslim-hating lunatic. This severe polarization in opinions has made him a popular topic of conversation within the media and more importantly in our homes, work places and social gatherings. What’s more, it is increasingly clear that in the upcoming elections, people may vote based on their like or dislike for him, hence making this a most compelling discussion to have. Interestingly this polarization is a phenomenon that is not only restricted to society but has also caused major political upheavals such as BJP veteran LK Advani taking a backseat and the withdrawl of support from Nitish Kumar’s JDU.

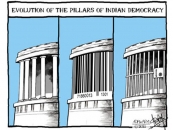

There are a number of reasons for this complete divide, it is perhaps important to identify the defining characteristics that society ascribes to Mr. Modi. Known for his autocratic style of governance, Mr. Modi is revered by his supporters for his efficiency and Industry-friendly economic policies and is touted by people within and outside the country as the man behind Gujarat’s impressive growth story.

On the flip-side, his critics criticize his economic policies for not fostering inclusive growth. Despite impressive industrial and GDP growth, Gujarat has failed on a number of social indicators. Most strikingly, it has failed the most vulnerable demographics of its society i.e. its women and children. Almost one in every two Gujarati children is malnourished and every three out of four are anemic. Gender bias in Gujarati society also appears to be particularly bad with an abysmal sex ratio of only 919 women for every 1000 men; way below the national average of 940. But besides the increasing inequality, perhaps the most troubling aspect of Modi’s public persona is that he is seen as heavily anti-secular. The Gujarat riots of 2002 is the single biggest tarnish to Mr. Modi’s political career and is arguably the largest contributing factor to the anti-modi sentiment within sections of society. Opponents of Modi hence argue that the moral, ethical and social costs of growth under his governance have been much too high.

It is important to discuss the lines along which society is divided with respect to this debate. The first noteworthy division is along the lines of political ideology. This is perhaps the first time that one sees political ideology actually having a place in political discourse in India. With some over-simplification by the media, we are seen as having two defined choices; a centre left UPA characterized by populist development policies, and a centre right NDA with its pro-industry stance; championed by Mr. Modi.

Being a former RSS man and popularly associated with ‘Hindutva’; Mr. Modi has also raised the significance of identity politics in India today. This is particularly due to his inaction in containing anti-muslim riots after the burning of the Sabarmati express that killed a number of Hindu pilgrims. It is therefore likely that minorities including India’s large Muslim population will oppose his candidature while a majority of Hindus might feel comfortable casting a vote in his favour.

Perhaps the biggest fault line however, and one that has not been reflected upon adequately yet, is the big moral and philosophical debate that this election, and the campaign of Mr, Modi has thrown wide open. This is of utmost relevance in the Modi debate because supporters of Modi often acknowledge that his reputation, due largely to his mismanagement of the 2002 riots, has been tarnished; but are willing to overlook this in the interest of sustained economic growth and prosperity for the nation. On the other hand, his critics are cognizant of his economic achievements but do not endorse the election of a man whose morality is in question, simply to achieve economic prosperity.

It is perhaps this distinction that makes the debate between supporters and opponents of Modi so difficult to reconcile. His supporters believe that given India’s current precarious position, regardless of his past, Modi provides India with its best chance to succeed. His critics on the other hand make a moral objection, which is at the core of it driven by emotion.

In his legendary book ‘The Prince’ Niccolo Machiavelli asserts “In the actions of all men, and especially of princes, where there is no court to appeal to, one looks to the end. So let prince win and maintain his state: the means will always be judged honorable, and will be praised by everyone”. Machiavelli’s ideal leader is one that places the interest of the state over ethics and one who is willing to take on amoral action if necessary to maintain the interest of the state. In direct contrast, Gandhi propagated peace and morality at all costs and his ideal leader may be characterized as someone who rules with compassion. It is thus sufficiently evident that Modi would fall more under the Machiavellian definition of an ideal leader. Extending this analysis further, Gandhi’s outlook on life was influenced extensively by Hindu philosophy. The Bhagawad Gita emphasizes the importance of detachment from end results and preaches that acts and duties must be carried out in a manner that is in keeping with good moral sense. It is therefore ironic that the supporters of the BJP (that propagates Hinduism) are the ones that are subscribing to a stance, which is in direct contrast to traditional Hindu philosophy.

The International community meanwhile, seems to have made its choice. The most conspicuous turn of events occurred when the UK government lifted a 10 year ban on Mr. Modi entering the country, which had been placed after the 2002 riots. Upon visiting ‘Vibrant Gujarat’, an annual high profile meet for investors, UK officials probably calculated that the gains from trade with Gujarat were too high to be foregone due to concerns over human rights violations. Our electorate will in like fashion also be forced to reflect on whether we are willing to make moral concessions to achieve successful industrial/economic growth. On a positive note however, it has been a while since voters have had a chance to exercise choice between different ideological and philosophical paradigms.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of the publisher