Call him the Kabuliwala or Bioscopewala, that image of a tainted outsider waiting to commit dastardly crimes against children is common to all cultures. The perpetrator however is not always an outsider, but an insider as recorded a million times. Someone we trust, respect, in fact, someone in charge of our protection. A figure of powerful authority. Rabindranath Tagore’s story Kabuliwala was written at a time when our society at least was in denial. Few knew that child abuse belonged to that cluster of domestic crimes committed by those we love and trust. The poet wrote about an outsider, a wandering Pathan, a money lender by profession. Tagore’s poignant portrayal was to liberate the Pathan’s image from that of a tainted common criminal. And this man’s deep yearning as a father redeemed him. Made him a frequent visitor to Mini’s home- established his social acceptance by a liberal writer – Tagore’s own portrait.

Mini had two fathers. Her real life writer father and the Kabuliwala. For the latter she is a glowing beacon of the little girl he left back in Kabul. Both men bond as doting fathers. The Kabuliwala bonds with a little Mini by virtue of his innate innocence – and his protectiveness for the child. Initially, Mini too is terrified when the Kabuliwala first visits them. Gradually he wins her trust – and in childish wonder Mini asks how many kids are hidden in his huge jhola!! Like the rest, Mini too is infected by the popular view that Kabuliwalas are kidnapper. Children are gifted with unconditional love. So is Mini who quickly becomes the reason for the Kabuliwala’s survival in a hostile society and an alien land.

Source: Wikipedia

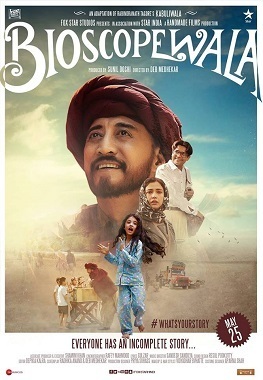

The story of this profound unconditional love between Mini and a rank stranger, the Kabuliwala, crafted by Tagore more than a 100 years back remains a timeless tale of human trust that crosses socio-cultural barriers refusing to date. This was repeatedly manifested by all the versions. The IPTA staged version with Asif Shaikh as the memorable Pathan. Add to it the magnificent Chabi Biswas in Tapan Sinha’s Bangla Kabuliwala. And Balraj Sahni’s portrayal defies adjectives… and now Danny Denzogpa as the Pathan is poignant, fragile and deeply effective. Debashish Medhekar makes his screen debut with the Tagore’s masterpiece renamed, Bioscopewala.

Debashish turns the Pathan into a roaming Bioscopewala. Kids flock to see through his kaleidoscope. This shift at once lifts his work into a multi-layered dimension – enriches it with nostalgia of old film songs from Shree 420. It is visually enriched as well. He makes a statement against the Talibisation of cinema. In Kabul, brute forces break the Pathan’s bioscope, call it sinful to watch moving images. He has to flee his country for political exile.

Source: Wikipedia

Wandering Pathans have long vanished from the urban landscape. Growing up in Calcutta city we were lulled into submission by elders speaking in hushed voices hinting about those chele dhoras (children snatchers) or Kabuliwala lurking about. Projected as kidnappers, thieves or worse – we formed a fearful image of the Pathans that is totally unacceptable in civil society.

Rabindranath’s short story leaps several decades in Bioscopewala. In this recent version Mini is the main protagonist, placed centre stage. Her photographer father appears briefly. Characters come and go. And when Mini discovers the ailing Pathan lying hidden, she is petrified. His presence disturbs the serene home ambience – rattles Mini. Until she realises he is her Bioscopewala from past…for me, the most moving part was Mini taking on her father’s unfinished journey. Through the war ravaged landscapes of occupied Kabul she searches in vain for the Pathan’s daughter – only to stumble on her grave.

The maker’s deep humanism, his concern about unchanged situation about recurring child abuse or support of cinema as art, is apparent. All this comes from conviction about the senseless inglorious crimes committed in the name of religion. It makes the director choose a different route – a cinematic journey that explores sensitive issues with stunning images. Sandesh’s lilting music accompanying Gulzar’s catchy lyrics - (the only individual from Bimal Roy’s era) - enhance the film. I wish however we had more screen space of Danny who puts in an extraordinary performance. I vote him a sure award winner…

And of course Bioscopewala deserves wide viewings. If not to revisit Tagore’s hallowed terrain – but also to watch a promising young debut at work. Here’s what Debashish Medhekar had to say to a few questions I had for him.

Rinki Roy (RR): I was curious why you chose Rabindranath's renowned story Kabuliwala to present a growing menace - abuse of girls? Arguably the problem existed behind closed doors always- but to bring it back through a well-known character like the Kabuliwala into today's context - is what I am curious… almost a hundred year leap? Speak openly .

Source: The Hindu - Debashish Medhakar

Debashish Medhekar (DM): In all honesty, this is Sunil Doshi’s pet project. He had been working on it for some time and had had a basic framework of the story in place even before I came on board. It is a tribute to his father and to his son, Ilann. When he spoke to me about it, I was thrilled. My mother is a huge Tagore fan, she taught herself how to read and write Bengali so she could read Gurudeb’s writing in the original, which is also, why I have a Bengali name.

RR: What made you select Tagore's Kabuliwala (written in 1892) and pour it into a contemporary mould?

DM: Once I was on the project, as a writer - I knew I had to make it my own, to put my own indelible mark on it, that would give me the satisfaction of having truly put myself into it - which is how the extrapolation happened. I knew I was walking on Holy ground here, with Tagore’s story, with Bimal Roy’s legendary cinematic production; but that’s what kept me honest, kept pushing me - to do justice to the innocent core of Tagore’s characters while contemporizing and corrupting the context in which they are placed and the conflicts with which they are faced. We brought in topical issues about the loss of homeland for refugees, dealing with personal loss, estranged relationships. The film is also not treated like a traditional drama piece, it has a ‘whodunnit’ aspect to it where she pieces together the puzzle that is the Bioscopewala and in doing so discovers herself as well.

RR: Were you aware that these wandering salesmen from Kabul had a notorious reputation - said to be child lifters and seen as criminals?

DM: In Tagore’s short story as well as the original cinematic presentation produced by Bimalda and directed by Hemen Gupta – the mother is the skeptic, she voices her concerns about the big burly Afghan man being allowed to interact with the little daughter. Little Mini herself runs from him when she sees him first thinking he will carry her away. So – yes I was aware of the stereotype associated with the Afghans but chose to play against the grain.

RR: If that was true in Tagore's time, how would they be seen now?

DM: There is a tendency, a very human tendency to suspect that which we aren’t acquainted with. The Kabuliwala represents that, an enigma to be discovered, it is something I have tried to retain in Bioscopewala too. But instead of suspicion, I dealt with the subject through nostalgia, through the fulfilment of longing for the past. . You see the Afghan diaspora all across Europe and the Middle East – at shops, in Taxis. They are honest, hardworking people who have suffered much at the hands of civil strife. The world is becoming aware of their suffering, the stereotype is changing.

RR: And why did you choose to present Mini's point of view?

DM: Kabuliwala both the short story and the cinematic versions, have become ingrained into our social consciousness and yet it feels like a distant memory getting hazy with the passage of time. When I re-read the story, re-saw the films it felt like someone from my own past had reached out and an old familiarity was instantly established. I wanted my Bioscopewala to feel like that, someone lost in time that one rediscovers with gladness. A lot of people said we missed scenes between Bioscopewala and Little Minnie but that’s what I wanted them to feel – an aching longing, a desire for more. That is what drives Minnie’s search for his past. I felt it was the best way to tell a story, from the point of view of someone who has forgotten a much revered childhood bond, through someone who is willing to exert herself to relive that bond again.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)