-853X543.jpg)

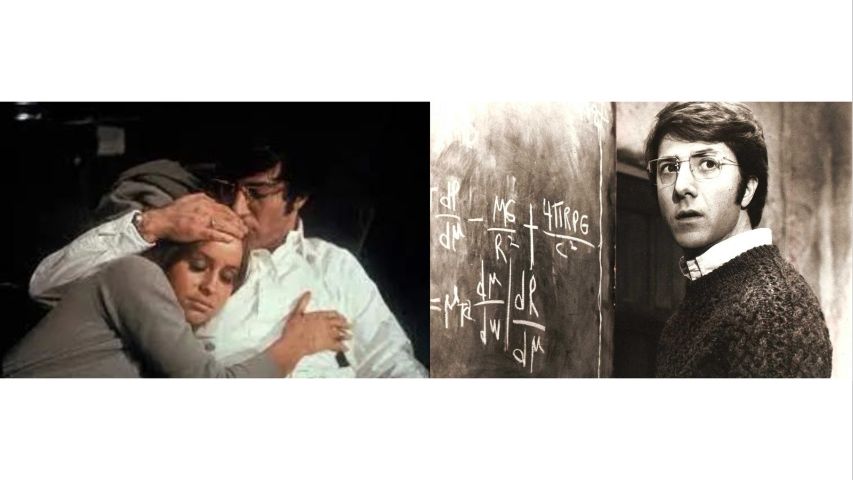

STRAW DOGS: POETICS OF VIOLENCE OR MISOGYNY?

by Vandana Kumar August 23 2023, 12:00 am Estimated Reading Time: 12 mins, 49 secsBased on a novel by Gordon Williams – ‘The Siege of Trencher’s Farm’, it was also my first exposure and my starting point to Peckinpah’s cinema, writes Vandana Kumar

Sam Peckinpah’s ‘Straw Dogs’ (1971) is about the aesthetics of violence and a lot more. The film disturbs you from the word go and strangely as the discomfort increases, you find yourself hooked – almost unblinking till the last scene.

The film is set in a rural English town where a young couple recently shifted and rented a house. ‘David Sumner’, played by ‘Dustin Hoffman’, is an American astrophysicist with a grant to do research. ‘Susan George’ plays ‘Amy’, David Sumner’s wife. She is English and hails from this small town. In the opening sequence the couple run into one of Susan’s old flames, the ‘Ex’ – ‘Charlie Venner’, played by ‘Del Henney’. He seems everything that David is not – rustic and oozing raw physical energy. He dwarfs David completely. Dustin Hoffman is at his timid, mousy best. Add to this a teasing sex appeal that Susan brings to the film. The opening scene crackles with anticipation – you know these are personality types who will start to clash along the way.

Apparently, the film was a censor’s nightmare like many of Sam Peckinpah’s films. That man is innately good, empathetic and shunning violence is a premise turned on its head. Man is basically violent, deep down and not so deep down too. It is this demon, of wanting violence and repressing this violence, that Peckinpah asks the audience to be bold enough to confront. Peckinpah said in various interviews, at the time of the film’s release, that violence is usually typically attributed to age old motivations like protecting one’s property or in a patriarchal way, one’s wife. He rather felt that violence has more to do with our “primitive thirst for blood”.

The story is about all that simmers beneath the regular every day. It is about the calm that gets shaken and the contradictions that come to the fore when David hires Amy’s ex- boyfriend and another couple of local guys for working on the Sumner’s garage. So, while the plot is straightforward, every progressive scene keeps mounting the tensions, both between the protagonists and between classes. By the end of the film, one is stripped of all illusions. There is no sanctity to anything anymore. There is each one’s demons and darkness. It is a clash of different darkness, too.

The marriage between David and Amy is not one made in paradise. It becomes apparent that sexual attraction is the pulling force here. Scratch the surface and you find David’s condescension towards Amy. He is an academician and often his words would make you feel that he sees his wife as no better than a dumb blonde doll. Apart from the flirtation, repartees and physical undercurrents, there is practically little going for the marriage.

David is incredibly patronizing towards the wife’s intellectual faculties. She introduces her husband to the ex-boyfriend saying that he studies celestial etc. He cuts her off by saying “nice try”. In a scene when the couple are enroute home, he deliberately changes her choice of music to western classical on the radio.

The issues that escalate around the home and town on the arrival of the Sumners also pivot around Mrs. Sumners and ambiguity surrounding her behaviour. She seems like the quintessential wild child of the nineteen sixties and seventies, walking brazenly without a bra. Peckinpah establishes the male gaze from the word go. There is blatant ogling, especially by the workers and the ex-boyfriend. The opening scene shows her in tight clothes, and aware of the nipples showing. She stokes sexual tensions, sometimes consciously, to see if her husband will stand up for her. She is also flirtatious. It is a layered game of provocation. Kissing her husband in front of her ex and his friends is one such incident in this game.

Amy and David have other issues too, simmering. It perhaps comes from a desire for attention as she gets very little of that, apart from when there is banter and sex between them. The professor is totally consumed with his Mathematics and formulae. He wants to demarcate work time and sex time, but she wants to distract him at the precise moment he sits to work. This childishness leads to further provocative behaviour, one that has grave consequences and spills into unimaginable violence and ruin of the country home in the climax.

Amy resorts to flirting with the workmen at their farmhouse. They interpret the flirtation as a come on. They are also amused by what they perceive as the husband’s weakness when he lets them respond objectionably and witnesses the game being played. The workmen want to play out what is being promised to them. They get turned on when she shows a glimpse of her naked self from indoors as they work outside. She knows the outsiders are looking inside. In one scene while working outside, the workers smell her panties drying and crudely express that they want to be where the panties were. She tells David that the rat catchers are staring at her and stripping her. He retorts “They will, if you go braless”. What is the dividing line between flirting, provoking and simply exerting your independence…?

The workers and Amy’s ex-boyfriend find it incredible that here is an academician who can’t fight them, or ask them to back off loudly and in no uncertain terms. They can’t fathom David’s pacifist and non-confrontationist behaviour. The men seem to be almost saying, through their expressions, that in our parts we would smash the living daylights of a person who messed around with one of our women. To make things worse, David tries to befriend them and falls for another trap of being ridiculed further by them.

Here the complexity is also because of Amy’s ambivalence. Is the going braless that real freedom or actually a way to get the man to notice her. There can be endless ways the audience, that is the women and men watching it, themselves process these scenes. This film has been a playground for not just the study of masculine toxicity, gender equality, but all the unspoken zones lying in-between.

Sam Peckinpah apparently moved away from the western genre in this film. This wasn’t a western by definition. The film was set in the late 1960’s in England and not in John Wayne’s land. Yet it evokes a similar feeling at various levels. There is that fight with the bad guys in the Badlands. It is in the end a fight that one man takes up (albeit grudgingly) against a system being run by a group of hoodlums.

The film takes us to David’s running away from the political climate of America. The ‘America vs. England’ also runs in the ‘outsider vs. the insider’ cat and mouse game being played.

In a very telling scene, the workers say that they hear ‘America is no good and that blacks keep getting shot’. They then say that ‘we have seen it all between commercials’. Amy finds it discomforting that the workers think her husband is odd. She wants him to conform. She tells her husband that they find him strange. He says “Why? Because I am American?” The xenophobic behaviour of the workers escalates to a final confrontation - the macho protective male inside every man, even one who wants to stay away from confrontation and is a pacifist.

But more complex is the layering of the rape scene that gradually spills into a grey zone of apparent willingness of the victim. One need not have done a textbook analysis in some school of cinema to imagine the amount of articles on the language of violence in the film – even if nowhere as close to studies on the cinema of ‘Quentin Tarantino’.

A trap had been laid for the ‘intellectual David’ to be outside of the home turf when the rape actually happens. A central point is a moment during the camera’s capture of Amy's first assault where it seems like she is enjoying what is being inflicted on her. There is that fraction of a second when she embraces the face of her violator that is suggestive of her tacit encouragement. She acts in a way that implies that she is encouraging the continued violence. This moment is what has been interpreted in every conceivable review.

The audience is barely able to process this moment when the camera shows us another sexual assault. This time Amy’s response is fear, revulsion and a clear disgust with no ambiguity. The screen brilliantly depicts her contradictory feelings which swing from scene to scene.

A woman dealing with rape does not always come with a formula. It is a lot more complex. Everyone deals with it differently. There are zones of physical abuse that most boys and girls have gone through during childhood. Some have gone to therapists; some have found peace by mentioning it to a parent or confronting the culprit. Others have lived an entire life trying to suppress it. That she kept quiet is not even a point to debate. Not mentioning it to a husband, a lover or to the family is entirely relatable. From ages 7 to 70, across continents and cultures, haven’t women hidden these moments of violation?

Could be a fleeting zone of involuntary physical or bodily pleasure. Not that the rape is justified by anything. The second time around she is terrified and disgusted. I don’t think Sam was trying to put any convoluted logic to it. He was just showing the audiences that these problematic zones exist. There was a huge risk taken by the director and every likelihood that he would get pronounced a misogynist, as indeed he got labelled on various platforms.

There is no denying that Amy’s capricious and childlike behaviour escalated the issue. But rape wasn’t being shown as something she deserved by the director. It was being shown as a fall out of a lot of repressed issues. The ‘outsider husband’ had to be shown he wasn’t man enough and that those men could send him on a wild goose chase while they ‘took turns’ with his woman.

The blood bath of a climax, had in fact from David’s point of view, nothing to do with the wife’s rape. He was unaware of this traumatic event. There was enough that had already riled him and provoked him to take on the job of protecting his home. The ‘let’s ignore these people’ got transformed into ‘nobody messes with the family and gets away with it’. It wasn’t revenge for rape. The most noteworthy difference in the book and the film is that the rape scene is nowhere in the novel.

The climax that leads to David turning everything around is one that the director points to from the first scene. Amy’s ex-boyfriend and gang are sons of the soil and toil on the land, they play rough sports and drink in the bar. The evenings are about who is sleeping with whom and the virile banter. David can’t fit in there. He has no business being there. He is the loser who can neither handle the wife’s sexual overtures nor control the men making advances. A man who ran away from the political climate of America and couldn’t fit in…all these contradictions lead to the end and the transformation of David. It isn’t just the last half an hour.

The complete destruction and revenge and a burning farmhouse is the end. “I will not allow violence against this house,” becomes his final statement of assertion and annihilation of all those who harmed him, his wife and their home space. The gory climax was as controversial as the rape scene. Senseless violence or a reaction after being riled beyond limits? An instinct of protecting that took over...the debate can’t ever conclude.

Another aspect that the climax represents is the complete breakdown of the relationship between the couple and not just the enemies that they have built around them. The no connection between them apart from a ‘sexual’ one is also out in the open. They never really knew each other. This was a side of her husband that Amy had never seen. Perhaps it is like many familiar couples – apart from the obvious sexual chemistry there is no deeper love or connection. Do we really know what lurks beneath the surface?

The camera doesn’t show us much of the small town or its people barring the main characters, the couple and those who come into confrontation with the couple. There is a pub as a focal point of events, too, where differences are brought out through socializing politics. The American academician David commits sin after sin through his elite mannerisms and aloofness. He asks for ‘any kind of American cigarette’ at the Pub on a visit. Every utterance of his adds to the couple’s alienation. His sin is being from a different world and her sin is marrying one like him.

The moors carry a sense of foreboding. The sterile barren lands don’t seem welcoming to anyone. This is perfect both to accentuate and to escalate the violence. Reactions to the film ranged from the audience calling it a Bible of cinematic violence to people feeling repulsed and calling it a ‘one hour, forty one minutes lesson in patriarchy and vile masculine toxicity’. Women’s responses too have been different. Some people feel it is sheer cowardice not to have the moral courage to fight for things dear to you, both people and values.

When the film was released, it was no doubt massively targeted as a misogynist tale. Interestingly, it was appreciated in equal measure as a story that dwells deep into man’s destructive and violent mind. In 2023, not much has changed and it can equally be seen as both. The relevance of the film needn’t be further underscored.

I totally enjoy the poetry of crime and murder. Filmmakers like Hitchcock create an atmosphere around crime. Chabrol makes us feel uncomfortable about dysfunctional characters in his films. Peckinpah’s ‘Straw Dogs’ takes it a little further and pushes you to face your own demons. This wasn’t just any character…could this well have been you?

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)