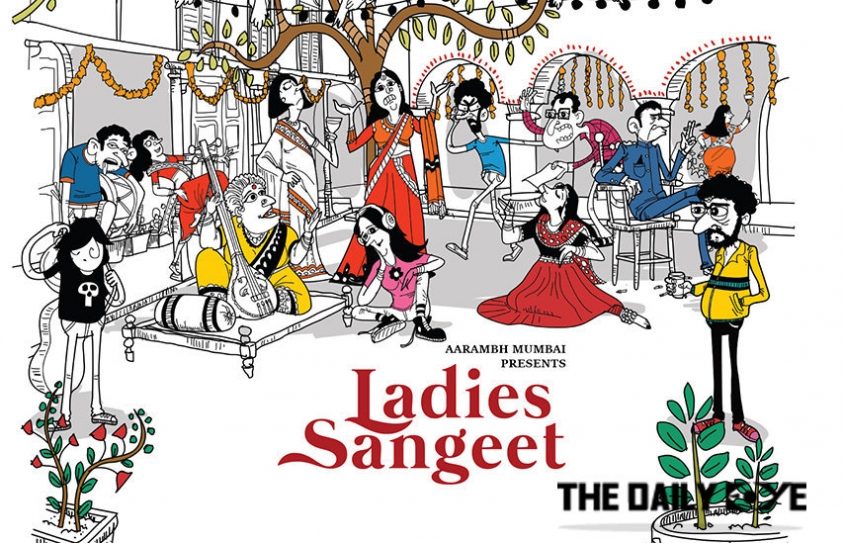

The North Indian pre-wedding ritual of the Ladies Sangeet, at which women gathered together to sing (some raunchy songs) an dance, minus the men. The custom has been modified and urbanized, and now wedding guests—men and women-- hire choreographers and dance to Bollywood hits.

Purva Naresh, who did a splashy production for Aadyam (the Birla initiative to encourage theatre) last year, scaled it down to perform at smaller and more accessible venues. The play with its wedding tensions and intense emotions flying around, did need a more intimate performance platform. Mercifully, Purva Naresh has not taken the Bollywood shortcut in her play. There is a lot of music but, thanks to Shubha Mudgal, it is traditional folk and semi-classical, some of the songs a pleasure to rediscover, particularly the one used at the climax.

In her family’s ancestral haveli, Radha (Shikha Talsania) is getting ready to marry her steady boyfriend Sid (Siddharth Kumar). She begins by grumbling about the heavy leheng abut eventually starts having severe jitters about the wedding. Her parents Yash (Joy Sengupta) and Megha (Loveleen Mishra) are estranged, because of his infidelity. Still, the mother is telling the daughter what she must do to look pretty, entice the husband and keep him tied to her.

Around the impending wedding, is the usual tumult of relatives, and the problems they being with them— an aunt’s thwarted showbiz ambitions, another’s complex about her dark skin, her daughter tied to her apron strings. An uncle married a former bar dancer finds that his wife is not invited to the wedding, though she lands up anyway and the expected explosion does not happen. The festivities, are being supervised by the bride’s grandmother (Nivedita Bhargava), a dominating woman, who believes in tradition. She wants to teach her skittish granddaughter, the bride’s sister, classical bandishes, while the young girl wants to do her own kind of singing. It comes as a shock to the gaggle of women that that will not be allowed to dance to film songs, the stern old lady won’t allow it.

Amidst all the confusion, is the comic relief of a wedding planner, with his outlandish plans, for the couple’s ‘entry’ and the neon lit ‘Radha ‘Heart’ Sid’ sign constantly going on the blink. He senses the tension in the air and is word weary enough to know that these days one wedding is not enough—most people go through at least two.

The play had potential to be an incisive look at the way ideas about marriage have altered with every generation, or how old patriarchal notions of what the ‘nayika’ is in classical bandishes should change now—the grandmother and granddaughter have arguments about that. The notion of class, gender equations, family relationships, parental control, youthful rebellion, outdated ideas of beauty or desirability – so much is touched upon, but superficially and not enough humour—though the lack of over-the-top melodrama is a relief. If the grandmother’s character is a bit clichéd, the mother is downright weird. A highly educated woman has oddly outdated ideas about marriage, sex and ‘how to keep the man check’ though her own formula of silence and withholding of intimacy haven’t worked for her relationship with her husband.

All the conflict moves towards a supposedly startling revelation at the end—which one can see coming much before it is mentioned—forgiveness and redemption.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)