The Law of the Land

by Revati Tongaonkar December 8 2017, 5:42 pm Estimated Reading Time: 2 mins, 43 secsEnvironmental lawyers and organizations across the world have begun to demand intrinsic 'rights' for nature- natural bodies, flora and fauna. The www.pri.org reported the development recently, underlining what this development means for environmental law.

Environmental law, as a subset of laws that address the effect of human intervention on the environment, is a fairly recent development in our judiciary systems. While humanity had begun to recognize the effects of its industries on the environment during the nineteenth century, the idea, that this nature needed protecting via various legal machineries, and the translation of that idea into functional legal structures developed a solid form in just the last century, which came to be known as Environment Law. This, along with a growing social conscience, led to a rapid growth in development of these laws across most developed and developing nations.

_.jpg)

The most recent development in environmental law, is the clamoring across the globe to recognize and establish the Rights of Nature. According to the Global Alliance for Rights of Nature on their website, to date, most legal systems on the planet treat plants and animals as property- of either individual persons or establishments (such as governments, municipalities, corporations, etc.). By recognizing the Rights of Nature, countries choose to protect nature as a separate entity, rather than as someone's property, and recognises that (sic) nature, in all its life forms has the right to exist, maintain and regenerate its vital cycles. This lets the environment the standing to bring a suit in court on its own behalf, without needing secondary representatives to defend its interest.

Environmental lawyer David Boyd explained the need for such a decree, saying that even though governments pass decrees to protect the environment, they do not have the 'same personal attachment' that individuals or communities do, and eventually look at it as property. Indigenous communities, meanwhile, who cherish nature often do not look at it as 'property'.

The breakthrough came with Ecuador choosing to include nature's rights in its constitution, setting a precedent for others. This amendment was made when, while drafting a new constitution in 2006 and 2007, a coalition of indigenous people suggested that the rights for Mother Earth, 'Pachamama' in the local Quechua language, be included as well. The idea was taken up and incorporated into more than 70 laws and policies. Another wonderful approach was the granting of legal standing to everyone- which means that any person in the country, regardless of their relationship to a particular piece of land, tree or animal can choose to defend it.

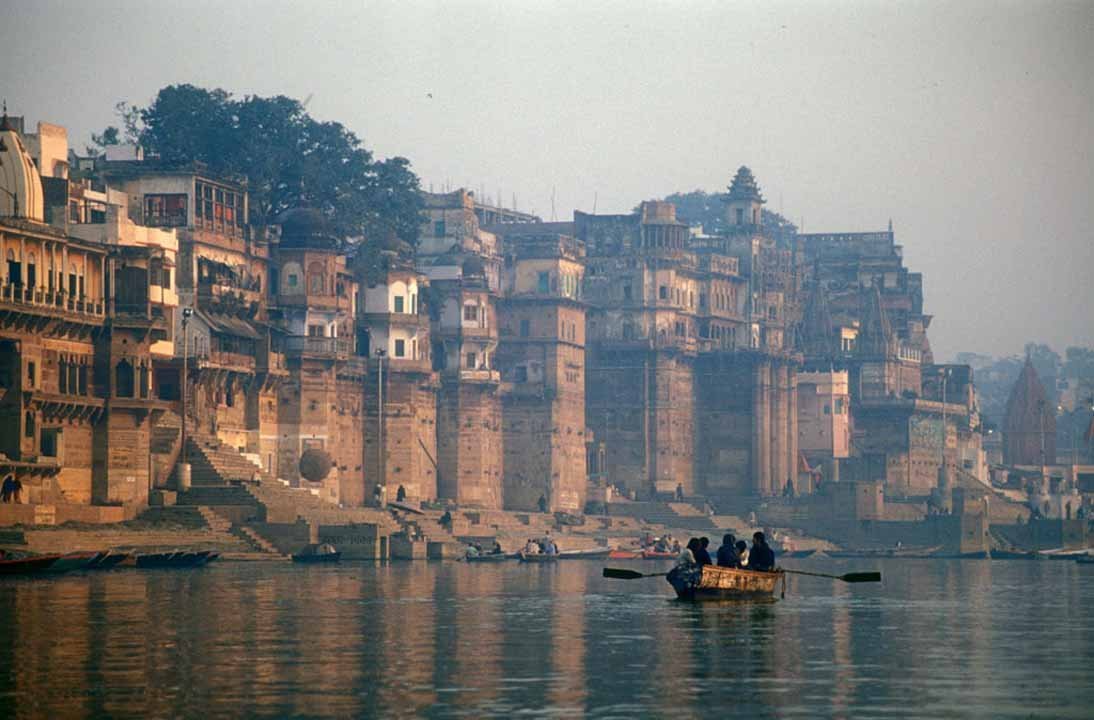

Several countries have followed suit- Bolivia developed such laws of their own, several counties in the states have passed a rights of nature ordinance to the same effect, and the Ganga river in India was recently granted human rights. New Zealand, too, passed its own set of nature's rights laws this year, granting personhood to a national reserve forest area, and a river, with help from the Maori.

This is, as Boyd notes, the first time that 'humans have relinquished assertion of ownership, and recognised that it's probably more sensible and certainly more sustainable for the land to own itself'. Perhaps tides are changing, and we are coming to realise that we are not above nature- we are part of it.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

_(7)-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)