-853X543.jpg)

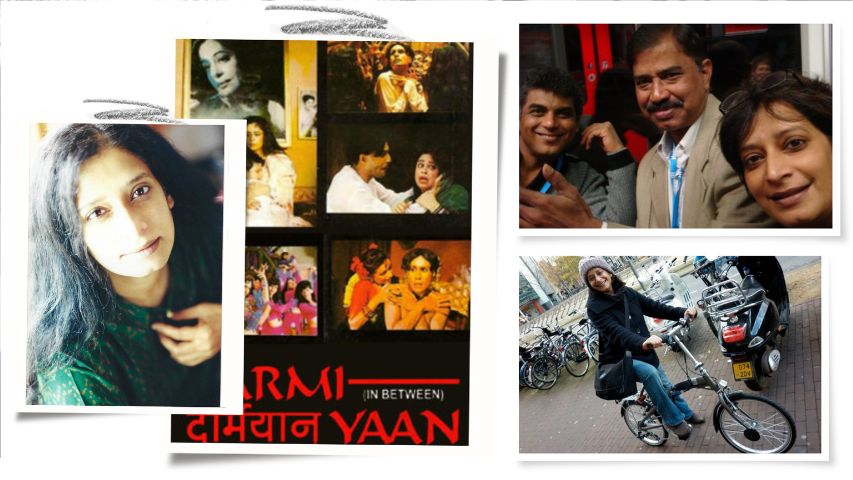

URMI JUVEKAR: The Storyteller

by Aparajita Krishna November 26 2022, 12:00 am Estimated Reading Time: 28 mins, 36 secsAparajita Krishna deep dives to writer Urmi Juvekar’s life and journey as a creative force and returns from the immersive experience with this collectors piece for screenwriters.

When I approached Urmi for doing a Q&A based on her person and her work, she was most agreeable, but also feared, ‘Why would anyone want to read it?’ My reply replied ‘Those who would want to read will. Your work merits a space. In any case we at The Daily Eye fortunately do not get bogged down by the notion of celebrity-status and market-demand. There is huge freedom in not being dictated. Every life has a story to tell. Do tell us yours.’ She did with a caveat, ‘I hope it does not sound banal. I just hope that I am not sounding like an idiot.’ I again brushed away her fears with a friendly admonition, ‘Nothing wrong in sounding like an Idiot at times.’

Just some handpicked names of her work will get the fear of ‘idiot’ out of the way. They boast of TV serial Yatra by Shyam Benegal, Bharat Ki Chhap, films like Darmiyaan, Shararat, Rules: Pyaar Ka Superhit Formula, Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye!, I Am, Shanghai, Detective Byomkesh Bakshi, Maya Memsaab, Sardar, documentary - The Shillong Chamber Choir and the Little Home School.

I have known Urmi over many years (1986 on) as a co-actor, colleague, assistant-director, director, film writer, producer, documentary filmmaker. She has lent herself to select works on television, documentaries, films, that have been uncommon and niche. Documenting them for this modest article was a revelation.

Her talk herein carries fascinating and informative anecdotes, admirable self-questions and uplifting lessons. She tells her life and work in the vocabulary of a very honest storyteller.

We have been colleagues of a valuable past. Back in the decades we were co-actors in Shyam Benegal’s defining TV serial Yatra (aired on DD in 1986 in 15 episodes), which was an incomparable experience of a journey on India’s longest running train across the length and breadth of India: from Jammu to Kanyakumari, from Assam to Rajasthan. Om Puri helmed the motley cast as Gopalan Nair from the Indian army. I think you played his wife. That was my first connection with you. Tell us all you would want.

Yes, I still remember meeting you outside the AC II class compartment, where all of us female actors were accommodated. By then I had played Om Puri’s wife in a documentary by Shyam Benegal about the groundnut co-operative as well as in another docu-drama by Ketan Mehta on alcoholism. Om remained a friend throughout. I had a very small role in Yatra. Actually, I never boarded the train in the series. I was the army man’s wife who is left behind as he boards the train to join duty. So, my bit had a fair amount of ‘rona-dhona’. It was an amazing experience even though it was short. Shyambabu had special equipment made so he could shoot in those narrow corridors. I shot mainly in Kanyakumari and a bit in Trivandrum. You surely remember how Shyambabu’s sets were. Everyone always hung out together. I remember feeling terribly envious when Salim Ghouse and a few others got a chance to travel in the engine.

Do apprise us in a summary of your parental background, siblings, education.

I was born, brought up, educated and lived my entire life in Mumbai. My mother was a teacher and father was an administrator in ICICI bank then. My sister and I were encouraged to learn music, act in plays. Like most of the Maharashtrians, I started with Ganeshostav, which used to be a hugely awaited annual cultural event. That is where all art-lovers presented their art. All that one needed was enthusiasm. I acted in plays throughout my school years. Later I won the Best Actress Award given by the State of Maharashtra during the state level competition. After that I did a little bit of theatre with Nadira Babbar. That is how I acted in my first TV series called Titliyaan. Nadiraji directed it. That is where I met Vinta Nanda. She handled production. By then I had finished my bachelor’s degree in Social Work from Mumbai University. But along the way I realized that I wasn’t really cut out for the profession so I chose to take up acting.

Do recall your chosen roles as an actor.

Just before Yatra, I got another role in Bharat Ki Chhap, a 13-part series on the history of science and technology in India. It aired on DD in 1987. The series was directed by Chandita Mukherjee. Immediately after the first schedule, she sat me down and asked me what I really wanted to do in life as she could see that my heart wasn’t in acting. She asked me to be her assistant. I agreed immediately because I could see during shooting that this project was exceptional. I was totally taken in by the subject matter. History of science was really the history of history. I was shaped by what I read and saw during its making. Till date I am a bit of a nerd when it comes to why something happened. We shot at various Indus Valley Civilisation locations, in mines, in oil rigs in the middle of the high sea. We travelled the country over two years in a bus for two-month long stretches. Then we would return, edit the material, write next episodes and get back on the bus. I can’t thank Chandita enough for that.

After that I joined Ketan Mehta as an assistant on the film Maya Memsaab (1993). Ketan was making Sardar (1994). It was on Sardar Patel. One of the finest Indian political films. I played Sardar Patel’s daughter Maniben, who devoted her life to him. Of course I was still treated as an assistant by Ketan and made to run around arranging things on the set.

You have over the years worked in media houses. We were colleagues at Plus Channel in the 1990s. The conglomerate as Amit Khanna called it (smiling emoji) was a very valuable learning and executing ground for a whole generation of television and film professionals. What was your experience like?

I met Amit Khanna during Maya Memsaab. He did the lyrics. Later, I asked him for a job and joined Plus Channel when it was moving from a video magazine to TV shows. We met again at Plus Channel where you did these amazing shows on music. I was always in awe of your work. You had a special eye for details and connections. Plus Channel was a very happening place. Do you remember how often Yash Johar, Satyadev Dubey, Johny Bakshi and a whole bunch of actors used to drop in to either meet Amit or Mahesh Bhatt, who was our creative director!

Plus Channel gave us a place to learn and grow. Amit pretty much left us to do what we wanted. He was the funniest boss! He also allowed us to make mistakes. That was such a bunch! You, Usha Dixit, Tanuja Chandra, Rucha Pathak, Vibha, Anupama Mandloi, Anuradha Sengupta! Am I forgetting anyone? Amit had collected a great gang of girls. Mahesh Bhatt too was a generous man. He gave his opinions freely, shared his insights. I remember how I used to take his books as soon as he finished reading them. He had a very eclectic taste and he always had interesting books. It was in Plus Channel that I met three of my future directors: Kalpana Lajmi, Onir and Gurudev Bhalla.

Was your screenwriting debut with feature film Darmiyaan (1997) directed by Kalpana Lajmi? The credit says it was written by Saagar Gupta. It had a subject and a premise, which was distinctly different: set in Hindi cinema of the 1940s it told the story of an actress who discovers that her son is a hermaphrodite. Tell us about the writing process.

Mahesh Bhatt used to write a column in a weekly those days. He had written an article on Tiku, a hermaphrodite son of a female star from the silent era, who never forgot the glory of his mother. I asked Mahesh to let me write a book on him. Instead he asked me to collaborate with Kalpana Lajmi who wanted to make a film on Tiku. That’s how Darmiyaan happened. Kalpana would come to the Plus Channel office in the evening when I would have finished my work. She and I would ideate and then I would write multiple versions of the story.

Kalpana was great fun to work with. She was tough, being one of the few women directors. For research she would host parties for yesteryear actresses, getting them to gossip. Kalpana had the guts to pick up unusual stories. She was very particular about her style. She liked to play with melodrama to bring out the irony of the situation. It was at times scary because I would find it loud and shrill but she never gave in. That is how she saw the world, in broad strokes.

Darmiyaan took a long time in making and I was writing Samna for Gurudev Bhalla, his first film, which I think did not get completed due to the producer going bankrupt mid-shoot. Kalpana continued rewriting the script with other writers. I was upset initially but Kalpana kept me informed about the changes or additions she was making. I was present during the shoot so I did not feel excluded from the team.

Darmiyaan gave me an opportunity to observe closely some fantastic artists: Bhupen Hazarika, Javed Akhtar and Asha Bhosle. A lot of the film was also created by Santosh Sivan, as cinematographer, who would force Kalpana to cut out the dialogues because he didn’t understand them. Santosh’s Hindi wasn’t great then. During the shoot he once replaced the entire scene by a single visual.

As a screenwriter I think I was exceptionally lucky because I was considered a filmmaker and not just a writer by all the director’s I worked with who let me be part of their process. This exposure kept me on my toes. I know exactly how a film is made and how sometimes a director is forced to deviate from the written word due to non-artistic concerns like locales, dates of actors or any other production calamity. It made me look at the bigger picture.

Did documentaries seek you out or you chose them? What are the chosen ones?

There were long stretches of no work. During one such period, I became friends with German documentary filmmakers. Through them I ended up making a documentary for ZDF-Arte along with some other films.

We used to make non-fiction pieces in Plus Channel for the TV show Mirch Masala. It was a form I was familiar with and liked very much. Those days I was constantly researching various documentary subjects. I still do that. I love non-fiction far more than fiction. Especially crime. It is said that at the heart of any story is a crime of some sort: moral, ethical, emotional, social. I feel all my films have been about crime. It is a genre of amazing possibilities.

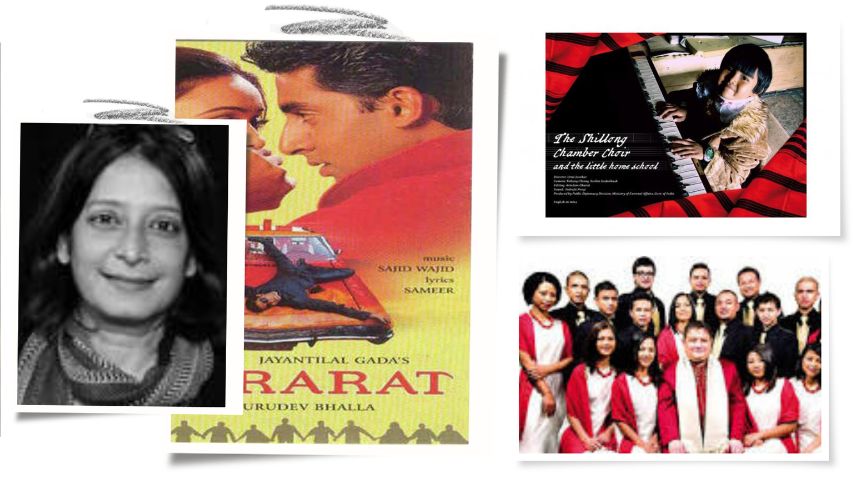

The Shillong Chamber Choir and the Little Home School, based on the Indian Chamber Choir formed in 2001, is a noted work. As a documentary you researched and directed it. The choir has gained such repute as a distinct voice from India’s North-East. It has performed in Indian cities and abroad. Along with hymns the choir also sings Mozart and the Khasi opera. Was it an alien subject or one you knew about? How was the creative process?

I was approached by the Ministry of External Affairs to make a film on the Shillong Chamber Choir. I hadn’t heard about them nor was I familiar with choir music. So, I got up and went to Shillong and spent time with Neil Nongkynrih. I fell in love with him and the kids, before coming up with the script. What I saw and felt there is in the film. I think the film captures Neil and his choir at a very specific time in their journey.

Neil was unsure of the direction he wanted to take. His fame was a much later phenomenon. In the film he is an artist who is reinventing himself after giving up his career as a concert pianist in Europe. He attracted children everywhere he went. His house is full of kids. It was a very moving experience but also fairly challenging because shooting, recording and editing live music has its own problems and I am not trained in music. But I had great support from everyone in the team. It was a tiny crew of five people including the editor and we solved all the problems together.

Film Shararat (2002) had you as co-storywriter. It was directed by Gurudev Bhalla. It starred Abhishek Bachchan, Hrishitaa Bhatt.

After Gurudev Bhalla’s first film was stalled, he saw a photo of an old man screaming at a young boy. That’s how Shararat started. My uncle had chosen to live in an old age home and what I saw during my visits there shaped the film as well as the line by Simon de Beauvoir where she comments, I am paraphrasing here, that old age does not automatically make anyone wise. If you were a silly young man, you remain so in your old age! It was a liberating statement at the time when ideas of unfulfilled old people weren’t acceptable.

Initially ABCL was supposed to produce the film with other actors. Abhishek Bachchan had just started out as an actor. He liked the script and that’s how the film happened. Again, it took ages to get released and I think more people saw it on TV than in theatres.

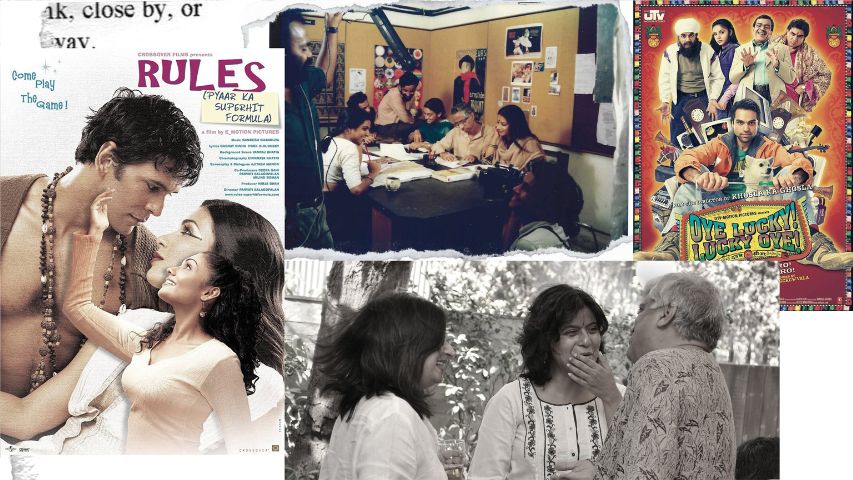

Rules: Pyaar ka Superhit Formula came in 2003. It was written by you and directed by Parvati Balagopalan. It starred Milind Soman.

At that time, I was surrounded by women who were obsessed about catching the right man or any man for that matter. It was also the time when books like ‘Men are from Mars and Women are from Venus’ were popular. To me it looked like a power struggle and strategies to win or at least make peace with men, of not towing the line. I had so much fun writing it. Really the film was actually about the wisdom of older women who managed their husbands with forbearance and who have a completely different opinion about romantic love than my generation.

Oye! Lucky! Lucky Oye! (2008) directed by Dibakar Banerjee was co-written by you and Dibakar Banerjee. It won the National Award for the most popular film and was supposed to be based on a real-life thief Devinder Singh (Bunty) from Delhi and his shenanigans. It introduced us to Dibakar Banerjee’s super comic-satirical take as a director. Tell us as a writer how was it to develop the script? The comic genre is perhaps the most difficult genre to address. It got critical acclaim and I am sure overtime it has become quite a cult film.

Ghost Ghost Na Raha, a script of mine, which remained an incomplete film, was initially offered to Dibakar. That’s how I met him. We ended up discussing various ideas but couldn’t find one that both of us were excited about. Dibakar shared his research on Bunty and a rough step out-line. I was immediately hooked but didn’t like his draft, except the childhood part, which was used as it is in the film. It is simply brilliant. For the rest, we went back to the drawing board.

The film really emerged after I met a journalist who was in awe of Bunty. He kept talking about the fancy cars Bunty drove even though they were stolen. Everyone we spoke to was star struck by him. That was the effect of liberalization of the country. Having money, being rich was becoming respectable. That is what Lucky is after. He wants respectability and, in his head, he is stealing a life and not objects. Also, how Bunty operated was so full of irony that one couldn’t help but laugh. His success as a thief is really about our vulnerabilities towards money. We could only tell his story the way we heard it. The crazy part is that all of his escapades are based on truth, we provided the link. The film although makes a scathing comment on the society and the times, it remains breezy and irreverent. That is why I think it has got its cult status.

The film evolved along the way. The idea for the beginning and end Crime Show bracket came much later. The film doesn’t have any classic structure. There are a lot of montages driven by amazing music by Sneha Khanvalkar. I think it is one of Dibakar’s best films. Manu Rishi did amazing work with dialogues. People often quote them to me.

In 2010 came Onir’s I Am, comprising 4 short stories from real life accounts. The story and screenplay have you in the credit along with Onir, Merle Kroger. It was cooperatively funded. Tell us about it as film-writing.

By the time I came on board, Onir was already shooting two stories, which were written by him and Merle Kroger. I Am is about identities and the crisis it creates in an individual’s life. Both Onir and Sanjay Suri were driven out of their homes. Onir from Bhutan and Sanjay from Kashmir. There was a clear longing for that identity, that life. But I was also aware of the plight of those left behind. Do they feel victorious? This understanding of the plight of those who are imprisoned in their homes, gives Megha the closure to her pain. In some way, she feels that she is better off than her Kashmiri friend who stayed back. The idea for I Am Afia came from the sudden media attention towards women opting for sperm donors to have a child. I was curious about the emotional journey of these women as they navigated this absurd landscape. That became the script.

Were you involved with Love Sex Aur Dhoka (2010) as creative producer, co-producer, story? It was directed by Dibakar Banerjee.

After OLLO, Dibakar started writing LSD with Kanu Behl. I had come back from attending Binger Script Lab for script development. I also got trained as a script consultant. Because of my new credentials, I was included in their writing process. Then I got involved in other aspects of the film and was credited as the creative producer. I like the film very much. It really captured the times of when people suddenly found themselves as both master and slaves of the newly introduced digital camera.

Shanghai (2012) has you as a screenplay writer along with director Dibakar Banerjee. As a political thriller it is said to be a remake of 1969 French film Z, itself based on a novel. Perhaps it did not do too well at the box-office. But how was the process of making it? The lessons.

Shanghai is an adaptation of the original novel Z by Vassilis Vassilikos. Set during the military regime in Greece, the novel is really about how power works. That became our main focus. It is not the nature of the regime but the nature of power that is important. How good systems are fallible if managed by corrupt people.

We worked with a point-of-view driven structure because right in the first scene you know who the killers are. What you don’t know is the why and how they will be caught. Will everyone be honest and courageous at that one moment that matters the most? That thought was primary in our minds. The only way to a just world is through us doing that one right action. If we don’t then we are as responsible for the mess we find around us.

It is quite interesting to see what it takes and why it is so hard to have the courage to stand up. It is never easy. What I liked about Shanghai is that characters are strangers to each other and are not driven by any intellectual conviction, but a very basic human quality of being just. Recently I read in a book that human beings are hardwired for justice. We may not express it or even practice it but every time we are affected by injustice, we are deeply hurt. The film had mixed reactions and I think it is mainly because, despite its light tone, it makes serious observations and does not offer a simple resolution.

I was told that Vassilis Vassilikos saw Shanghai when it was screened in Greece and liked it. That felt very good.

Detective Byomkesh Bakshy (2014) has you in the credit of screenplay. It was directed by Dibakar Banerjee. As a mystery thriller it is based on the famous character created by Sharadindu Bandyopadhyay. It garnered good reviews but perhaps could not match the box office expectations. That apart, tell us what you would want, of the experience.

Dibakar had a draft of Byomkesh Bakshi when I met him. The idea was to create a hidden story within the known history. Why didn’t the Japanese attack Kolkata? A simple case of a missing man opens an international conspiracy. This was the first case of Byomkesh who prefers to call himself Satyanveshi - seeker of truth. We wanted to give him a complicated truth to unravel. It was a coming-of-age story. There were so many ideas we worked with.

Leila (web-series in 6 parts) released in 2019. It was created by you and co-written. It was co-directed by Deepa Mehta. It starred Huma Qureshi. What was the reaction from the viewers like? Did it face some opposition from hardliners? And pray why?

Leila was a huge learning experience. I haven’t really written for television so I had to figure that out first. Also, I had never really worked as a script writer with a corporation where feedback notes play an important role. I had to learn that too.

Leila is an adaptation of Prayaag Akbar’s novel. The basic challenge was to convert the over 100-year timespan he deals with in the book into a manageable time span for the series.

It was fun creating the dystopian world. Every dystopia is someone’s utopia, that is how I looked at it. No one wants a bad world. It is just that people don’t agree with what is good or bad. I firmly believe that everyone has a right to an opinion or belief even if it is not what I agree with. I don’t think there was any push back or reaction to the series then.

In the present what films or web-series are being cooked or garnished to be served? Do update with your latest work in the making.

During the lockdown, I wrote a novella, which I hope will find a home and get made. Fingers crossed on that. I am also finishing a horror film script. So, let’s see how everything goes.

Dibakar Banerjee and you have had a very fine creative collaboration. Do tell us about his distinction as a writer-director.

Dibakar has a solid command of the medium. He is not insecure as a director so he listens. I always insisted on writing a full draft and so would he. Therefore, we would take turns to work on each other’s drafts until we arrived at what both of us agreed with. He had the final say with dialogues. He has a keen ear for it. I focused mainly on the story, structure and the theme. Sometimes Dibakar came up with brilliant ideas and would expect me to fit them in the screenplay. He would always say that I was a ‘structuralist’ and I took it as a complement. For me the theme and the narrative are very important. That is what creates a wholesome story and allows you to explore the world of your story without any preplanner outcome. Dibakar understood the value of it and mostly left me alone.

I must admit that with most of my directors, I was never excluded from the process. My opinion about casting, design and even editing was taken seriously. The only part of the filmmaking process that I don’t enjoy as a writer is the shooting bit. Having worked as an assistant, it’s very difficult for me to not give my two bits about what is going on. But as a writer, I believe that once a script is handed over to the director, I should leave them in peace. With Dibakar it was always exciting to see how he realized scenes. There was always something more than I had imagined.

A question I would be expected to ask at the beginning, but ask it now. Who all and what all shaped your own connection with film writing? During your cine-goer stage and later.

My stint at the Binger Film Lab, Amsterdam, has been the biggest influence. Not having attended any film school, I literally learned on the job. It has its advantages and disadvantages. Every time I wrote, I was winging it. But it was in Binger I learnt how to play with story and script elements without fear. There were ten writers and directors working on their scripts. We participated in each other’s writing process. I am no longer afraid to rewrite. I actually enjoy it.

Om Puri had acted in Shararat by Gurudev Bhalla and in another incomplete film then titled Ghost Ghost Na Raha that I wrote. Om also supported me with a grant when I was selected to attend Binger Film Lab in Amsterdam. He was chairman of NFDC then. That is how I could afford to stay in Amsterdam over six months working on a script. Writers don’t get such luxuries often.

In addition, my training as a script consultant helped me greatly to understand the process of writing. After Binger, I worked as a script mentor for NFDC Film Bazaar script lab for almost six years. I had a chance to work with Alankrita Srivastav on her Lipstick Under my Burkha, Sharat Kataria’s Dum Laga ke Haisha. I watched the writing process of Lunch Box and Geetanjali Rao’s Bombay Rose as it was part of our lab. These films taught me a lot about writing. Working with other filmmakers as a mentor or a consultant is a very rewarding experience and I am always looking forward to it.

I don’t watch or read much fiction. I am drawn to non-fiction. Fiction overwhelms me. I find it difficult to shake it off.

How do you see the present and future of independent films, as in not studio or corporate driven? The Hindi language cinema is either very mainstream, opulent, formulaic, or, else grappling with an independent vision. Will consistency come in? Hollywood, British, Chinese, Taiwanese, Korean films and TV content have stamped their mark one way or the other. Our regional language films are far more experimental and rooted. What ails Hindi cinema and its writing?

Hindi cinema, as we understood it, is now struggling to find itself. I feel one of the reasons is that instead of bringing people together, globalization has increased the assertion of separate identities. A previously marginalized community was now prosperous and demanded that their stories be told and in their own voice. That is how we now have more authentic stories from regions. What once worked as pan Indian cinema has become its weakness. Why watch a Malayali in Hindi when you can watch them in Malayali? Now people have learnt to make that distinction and I doubt that’s going away. Aren’t we watching more regional cinema now than we ever did?

The other day I was in a meeting for a Hindi film where neither of us were native Hindi speakers. How do you expect any rooted work from this group? I feel that we are witnessing many changes in how and what people are viewing. Monetization of the content is here to stay. But we know that content is not the same as a story. Stories will have to find an additional outlet.

It is impossible in our capitalist world to denounce money and talk about any other matrix that society needs. Converting stories into content backed by viewing patterns is only going to make stories reaffirm the capitalistic belief system. And now because of all the data harvesting, it has become easy to manipulate us to act out our basic instincts.

But I am an optimist. It’s not for nothing we are homo sapiens. We have the gift of storytelling. That is how we make sense of the world we live in. In our hearts we are curious to know the other. Stories help us with getting to know each other. Stories represent and reinforce our value system. Content may not do all that because stories are not bound to any form. Even after an apocalypse, the surviving few will continue to tell stories.

I think that like water, stories will find a way to come out. What that will be is unclear right now. What is happening with films is what is happening with the rest of the world. The world has changed but it is not the end. There is a lot of interesting work people are doing both in films and in web series. Giving the camera in the hands of people, cinematic language has evolved like never before. There are so many new forms and styles people are using now. I find that exciting.

I don’t want to be an alarmist and predict doomsday. With so much to watch and compare, we are expecting great work at greater speed. But good work demands time and it doesn’t happen often. There are always more misses. Just because now there is so much content, we can’t expect it all to be great. It is not possible. After all, films are fundamentally an art. They just happen to make money. There seems to be a bit of confusion on that these days.

As a film writer is the level playing field fair to a woman writer, economically and otherwise?

I never faced any overt discrimination because I am a woman. You know this is a complicated industry where personal connections make a difference as well as being at the right place at the right time. Success can be explained only in hindsight. How can I certainly say that my script was rejected because I was a woman and not because the script didn’t work? Maybe someone else can but that is not my experience.

All the men I worked with always encouraged me. I believe that we are the product of our times. Like when you are creating a character you look at his age and his times to understand him. I am bound by the times I am living in and by the location too. A woman of my age from Berlin would experience an entirely different world. I made peace with it long back when my great grandmother said that I was lucky that I could wear jeans. Her comment made me realize my privileged position. I was living her dream life.

I know girls after me will have more access to the top. For me there is no top writer position. There is only the richest writer position. I never applied for it. I am good. I never had to earn money through writing to run the kitchen. My husband, Chiang (noted cinematographer), took care of it while I did whatever caught my fancy. Around me, I saw men handle their careers differently. They had it tougher. Despite their talent, they had to make compromises to be able to have a normal life.

I sometimes wonder if I am sweeping my uncomfortable experiences under the carpet? I sure did face some difficult situations but I was brought up with a belief that wrong happened to you only if you wronged. So, I always blamed myself for them. At times I find myself making excuses for those men, thinking that they too are products of their times. It is great that women are not taking anything without a fight. This fight will change the next generation of men too.

As a woman how do the times sit on you? We have charted our own independent course as single women for a greater part of life. How easy or difficult is negotiating life and work?

I don’t exactly understand the question. But I am giving it a try.

All around me I have seen women work very hard and face adversity of every kind. And most of them just do what needs to be done. I don’t think that our challenges are any different from what all women face in general. The world is not a fair place. Not for women and not for the underprivileged. That’s how it is.

I have always focused on what I can do because that’s the only thing that is in my control. My husband suffered from a grave illness for twenty-four years and there were times when I had to drop everything and focus on his health. This constant awareness of death made me make the most of whatever was possible. There came that greed in me to have a good time now.

Here is wishing Urmi and her future a most lived life.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)