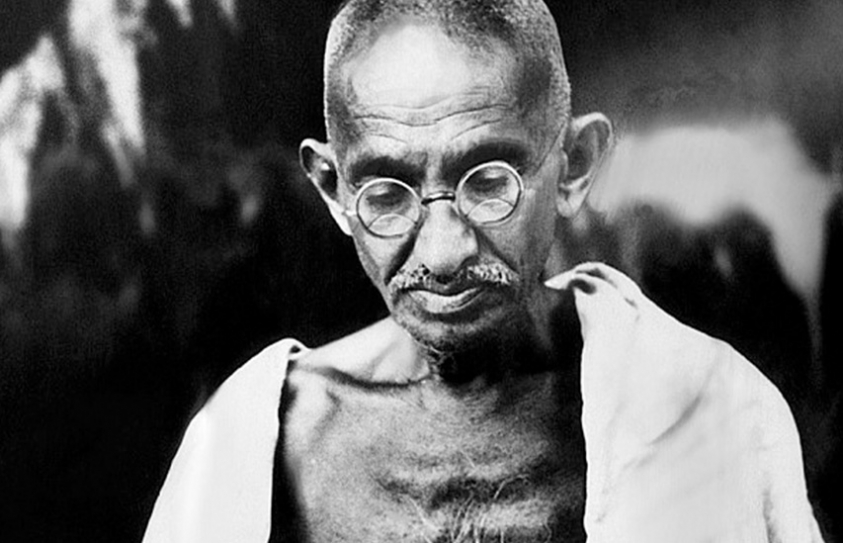

The caste system is still a contentious issue in most of India; in Maharashtra the Brahmin-Dalit problems persist, years after the flaring up of the anti-Brahmin movement following the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. This chapter of history has not been dealt with much in theatre, though there have been Marathi plays, like Gandhi-Godse, that were criticised for their anti-Gandhi content.

PL Mayekar’s Agnipankh is even more remarkable for his creation of a fiery woman at the centre of the family and social drama. Without a strong actress, like Mita Vashisht, with a theatre background, playing Baisaheb, a new production of the play might not have had an impact.

The play, has been translated into Hindi, from the original Marathi, though the Maharashtrian ethos has been retained. Agnipankh (using the imagery of the Phoenix from Greek and Roman mythology) is set immediately after Independence, and revolves around the inhabitants of a lavishwada (mansion). Baisaheb is a stern matriarch, who controls the zamindari of her husband’s family, but is shred enough to anticipate the social and economic changes that will inevitably come after the British leave; she has invested in factories in her town as well as in Mumbai. She has also sent both her children to study in the city. Her alcoholic and debauched husband Raosaheb (Satyajit Sharma) is happy to leave her to it, while he goes off on hunting and gambling sprees.

Baisaheb’s well laid out plans and strict Brahminical lifestyle go haywire when both her children go against her wishes—her son marries an outspoken woman from outside the community and the daughter falls in love with the Maratha son of her family’s servant. Even this damage Baisaheb makes effiorts to undo, what she is not prepared for is the anti-Brahmin movement that spread across Maharashtra following Nathuram Godse’s brazen murder of Gandhi. This coupled with the break-down of the caste system and the rising labour movement changed the fabric of feudalism in the state.

Mayekar’s play captures all these sweeping changes and lays them on the threshold of Baisaheb’s wada. This chapter of history may not be of much interest to today’s audiences, but the push-and-pull of family dynamics still makes it an engaging watch. Mita Vashisht (dressed in the finest silks and jewellery) has the stage presence to bring Baisaheb to life and Sharma with the character’s eccentric, and later, hard-held dignity in the face of chaos, lends excellent support.

The play, ably directed by Ganesh Yadav, is not the kind of play many producers would take up in these times when the audience preference is for entertaining plays. This one would fall into the thought-provoking bracket.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)